Scientists Discovered a Gigantic, 300,000-Year-Old Landslide Under the Ocean

Long ago, an almost inconceivable amount of sand shifted, changing the surface of the sea floor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/88/6c88f854-47c1-4187-a98c-97a742c729eb/reefer.jpg)

You’d think that in the 21st century, every inch of Earth—above and below water—would already have been documented and studied. But that’s far from true. Much of the ocean floor remains elusive to scientists, and a new study shows just how much remains to be found. As the Australian Associated Press reports, scientists have discovered remnants of a massive undersea landslide that occurred 300,000 years ago off of the Great Barrier Reef.

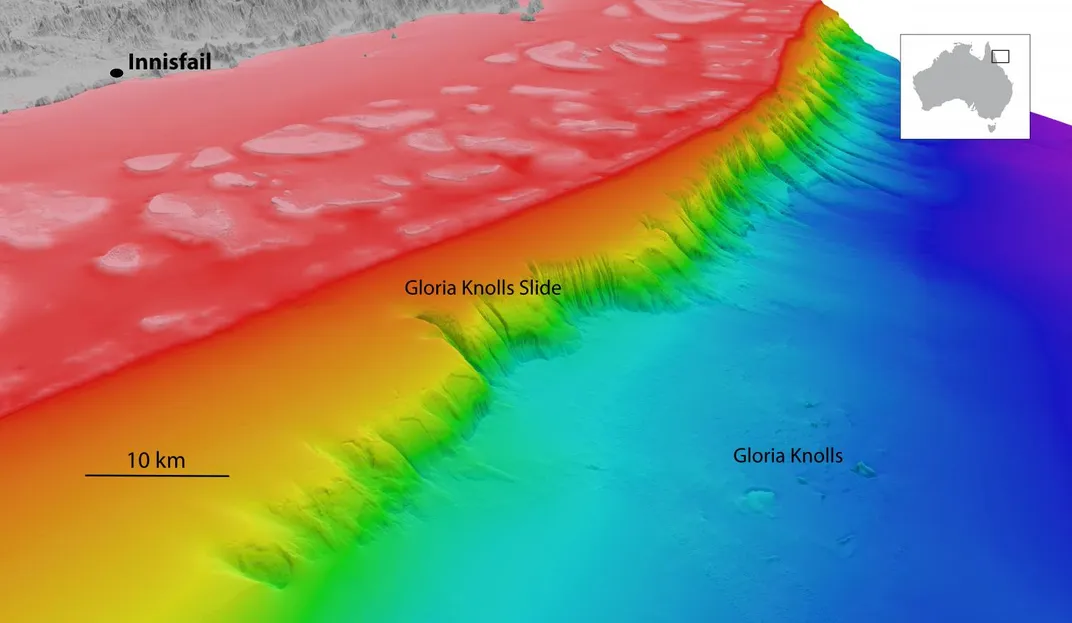

It’s an intriguing find in a location that has already yielded plenty of fascinating scientific information. The study, which was published in the journal Marine Geology, describes the remnants of a long-lost landslide off of northeastern Australia. The area has been named the Gloria Knolls Slide complex.

Scientists were using 3D mapping tools when they realized that they were sailing over a series of eight knolls that ended up being the remains of a landslide that happened hundreds of thousands of years in the past.

When researchers took samples from the area, they found coral fossils that were 302,000 years old. As the AAP notes, the landslide happened before this now-fossilized coral grew. Some of the knolls were up to 4,430 feet deep and over 1.8 miles long, and they were located up to 18.6 miles out from the spot where the landslide’s main remnants were found. They think that the landslide was likely caused by some kind of seismic event and a rising sea.

All in all, they believe that the landslide displaced 32 cubic kilometers—the equivalent of almost 3 billion dumptrucks filled with sand. They also discovered a community of cold-water coral on the top of the largest knoll. The displacement of all that sand seems to have created the perfect environment for these deep-sea corals, which don’t necessarily need sunlight to survive. Cold-water corals thrive on the edges of continental shelves and make a great haven for a diverse group of undersea creatures. The researchers say that the discovery further underscores the relationship between undersea landslides and the presence of cold-water corals—a relationship that, if studied further, could yield important conservation clues.

There’s a potential downside to the discovery—it could point to a tsunami hazard to the coast of Queensland, which would bear the brunt of a wave caused by a similar landslide in the future. But perhaps by further studying the landslide area, scientists can figure out exactly what kinds of threats Australia faces and help officials mitigate tsunami risk.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)