The Only Primate With a Toxic Bite Might Have Evolved to Mimic Cobras

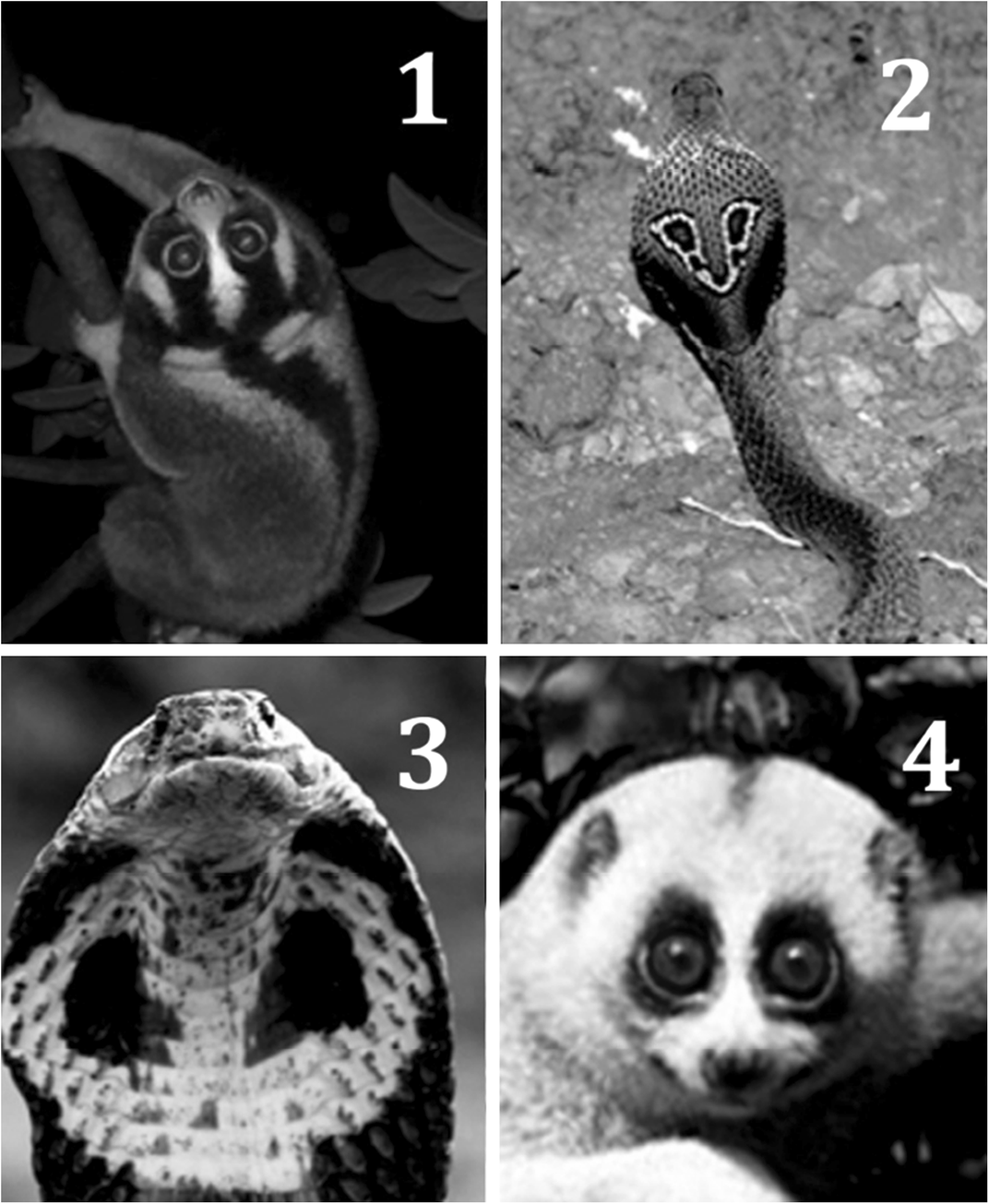

Slow lorises have snake-like markings, postures and a hiss that all resemble the speckled cobra

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/b6/6cb65f8d-1d74-4cd3-a270-616342141efd/42-33340777.jpg)

Slow lorises are known for their cuteness. Nocturnal primates that live in Southeast Asia, the lorises have round heads, big eyes, fuzzy fur, and—if they lick a gland under their arms and combine the secretion there with their saliva—a less-than-adorable toxic bite.

That bite, combined with a hiss-like vocalization, sinuous movements, and a distinctive defensive posture in which the loris raises its arms above its head, make the primate look remarkably like a spectacled cobra ready to strike. Which raises the question: Did the loris evolve to mimic poisonous snakes?

Yes, argues a paper published in the Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases last year. To back up this idea, the researchers noted that cobras and slow lorises lived and migrated through the same part of Asia about eight million years ago. Quick climate changes in the region stripped the Malay Peninsula of tropical forests and replaced them with drier woodlands. That opened up the loris’s habitat more and could have provided pressure to mimic a poisonous snake.

As a result, the researchers suggest, the loris’s markings resemble those of the snake, especially if the animal is encountered in the dusk of twilight, as one naturalist found out. John Still was living in Sri Lanka in 1905 when he heard a strange sound from his room:

With the breathing sound came the occasional quick hiss of a strike. So I got up and took a stick , for I thought that a cobra might be attacking my Loris, who was not in his cage, but only tethered to the top of it. The sound came from my room, where, although it was dusk, there was plenty of light to kill a snake.

As I went into the room I looked at the cage, which was on the floor, and on the top of it I saw the outline of a cobra sitting up with hood expanded, and threatening a cat who crouched about six feet away. This was the Loris, who, with his arms and shoulders hunched up, was a sufficiently good imitation of a cobra to take me in, as he swayed on his long legs, and every now and then let out a perfect cobra's hiss. As I have said, it was dusk at the time, but the Loris is nocturnal, so that his expedient would rarely be required except in the dusk or dark ; and the sound was a perfect imitation. I may mention that I have kept snakes, including a cobra, and am therefore the less likely to be easily deceived by a bad imitation.

"Few people have ever researched loris venom, so few hypotheses have been generated," lead author Anna Nekaris, the director of Oxford Brookes University's Little Fireface Project, told mongabay.com. "We are hoping that people would like to test the cobra hypothesis—it does have some scientific basis. But of course there are other hypotheses."

For instance, the primates are called slow lorises for a reason. Toxin might help them subdue the birds, bats, lizards and even tarsiers they are known to eat. But observations suggest that lorises can take down these animals and eat them fairly quickly—no paralysis needed.

Maybe the toxin helps protect against predators and parasites. Or, like the male platypus’s spur, it could have evolved to be used as a weapon during fights with other lorises. None of these explain the snake-like movements (an extra vertebrate in their spine gives lorises this ability), hiss and markings, but they certainly could have sped along the evolution of a poisonous bite.