How Forensic Scientists Once Tried to “See” a Dead Person’s Last Sight

Scientists once believed that the dead’s last sight could be resolved from their extracted eyeballs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/94/26948dab-97b1-495e-ad4c-7e7a32057cab/1599361851_dbab338ad3_o.jpg)

"Image on her retina may show girl's slayer," reads a headline from a 1914 article in The Washington Times.

A 20-year-old woman, Theresa Hollander, had been beaten to death and her body found in a cemetery. But the fact that her eyes were still open gave her family hope: Perhaps the last thing she saw—presumably the face of her murderer—was imprinted like a the negative of a photograph on her retinas, writes Lindsey Fitzharris for The Chirurgeon's Apprentice.

Accordingly, a photograph of the woman's retina's was taken, "at the suggestion of a local oculist, who told police that the retina would show the last object within her vision before she became unconscious," The Times reported. The grand jury would see the image on Saturday.

Though it may sound like folly these days, many believed in these statements at the time, which was a period of riveting developments in both biology and photography. People were well aware of the similarities between the structure of the human eye and that of a camera, so the idea that the eye could capture and hold an image didn't seem so far fetched. Indeed, some experiments made it seem possible.

The process of developing the retina's last images was called optography and the images themselves, optograms, writes Dolly Stolze for her blog Strange Remains. Experiments in this field first started with Franz Christian Boll, a physiologist who in 1876 discovered a pigment hiding in the back of the eye that would bleach in the light and recover in the dark. He called this retinal pigment "visual purple" and today we call it rhodopsin.

Wilhelm Friedrich Kühne, a professor of physiology at the University of Heidelberg, quickly took up the study of rhodopsin, according to Arthur B. Evans, writing about optograms. Kühne devised a process to fix the bleached rhodopsin in the eye and develop an image from the result. Evans quotes an article by biochemist George Wald about Kühne's work:

One of Kühne’s early optograms was made as follows. An albino rabbit was fastened with its head facing a barred window. From this position the rabbit could see only a gray and clouded sky. The animal’s head was covered for several minutes with a cloth to adapt its eyes to the dark, that is to let rhodopsin accumulate in its rods. Then the animal was exposed for three minutes to the light. It was immediately decapitated, the eye removed and cut open along the equator, and the rear half of the eyeball containing the retina laid in a solution of alum for fixation. The next day Kühne saw, printed upon the retina in bleached and unaltered rhodopsin, a picture of the window with the clear pattern of its bars.

People quickly latched on to the idea as a tool for forensic investigations. The College of Optometrists in the U.K. reports that police photographed the eye of a murdered man in April 1877, "only partly aware of what optography involved," and that investigators on the trail of Jack the Ripper may have considered a proposal to use the technique.

Faith in optography was misplaced, however, as Kühne's experiments showed that only simple, high-contrast surroundings were able to produce interpretable optograms, Douglas J. Lanska writes in Progress in Brain Research. Furthermore, the retina needs to be removed very quickly from the recently deceased. He wrote at the time:

I am not prepared to say that eyes which have remained in the head an hour or more after decapitation will no longer give satisfactory optograms; indeed, the limit for obtaining a good image seems to be in rabbits from about sixty to ninety minutes, while the eyes of oxen seem to be useless after one hour.

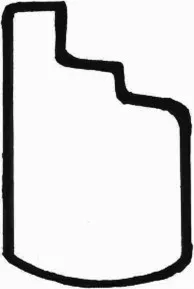

The only optogram known to have come from the eye of a human was developed by Kühne, writes Stolze. The man was Erhard Gustav Reif, sentenced to death for drowning his two youngest children. On November 16, 1880, Kühne took the man's decapitated head from the guillotine and created an optogram within 10 minutes. The image, however, is very ambiguous, as Kühne's drawing of it shows:

Kühne never claimed to say what the image depicted, but people have interpreted the shape as the guillotine's blade or the steps the man had to take to reach it. Both are probably fanciful interpretations as Reif was blindfolded shortly before his death.

Still, the idea persisted and leapt into fiction. Jules Verne used optography as a plot device in his Les Frères Kip (The Brothers Kip), published in 1902, Evans writes. The eponymous brothers end up falsely accused of the murder of a ship's captain. When the victim's friend asks for an enlargement of a photograph of the dead captain, the captain's son notices two points of light in the man's eyes. With the aid of a microscope, the faces of the real murderers, "two villainous sailors," are seen and the Kip brothers are set free.

For decades, people claimed to use the technique, at least if newspapers were to be believed. "Photos show killer's face in Retina," and "Slain man's eye shows picture of murderer" are just two headlines showing the optogram hype. Even more modern minds are tantalized by the idea: optograms appear in Doctor Who ("The Crimson Horror" from 2013) and in Fringe ("The Same Old Story" in 2008).

The photograph in the case of Theresa Hollander never did reveal anything to help or hurt the suspicions that her ex-boyfriend was responsible, Fitzharris reports. He was tried twice and found not guilty.