A Free Man’s Letter to A Former Slaveowner in 1865

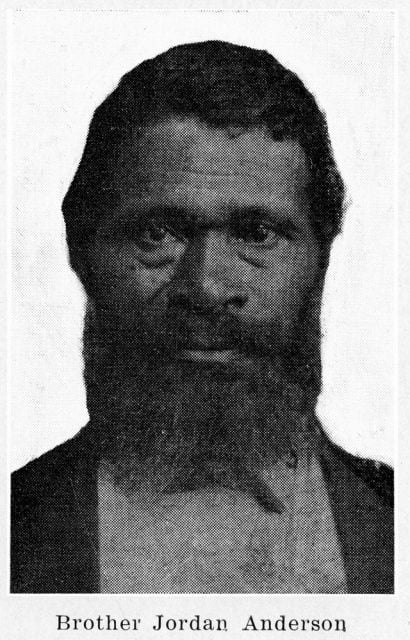

When asked to return to the farm where he was held in bondage, Jourdon Anderson wrote this thoughtful reply

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/f7/18f78684-2553-4fd6-8b7b-7a8f1319f1eb/ih137863.jpg)

For much of America's history, slavery was "omnipresent, from the economy to foreign policy, from the pulpit to the halls of Congress, from westward expansion to the educational system," writes Lonnie Bunch, the director of the African-American History and Culture Museum.

Perhaps that's why, in August 1865, a former slaveowner named Colonel P.H. Anderson asked Jourdon Anderson, a free man, to return to his Tennessee farm. The slaveowner's letter has been lost to the passage of time, writes Josh Jones for Open Culture, but Jourdon's response was published in a Cincinnati newspaper and survives to this day.

Based on his sardonically civil letter, it's clear what Jourdon thought of the Colonel. "Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon," he writes. But, he adds, "I have often felt uneasy about you." Jourdon, who explains he was freed by the "Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville" in 1864, had no need to consider the offer. He describes his life in Dayton, Ohio:

I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated.

In the letter, Jourdon asks that the Colonel what "good chance" he proposes to pay for the work. He also asks for the wages owed to him and his family: 32 years' worth for himself and 20 years' worth for his wife. The total tallied to $11,680, plus interest. The sly humor of Jourdon's response was no rare thing, report Allen G. Breed and Hillel Italie for the AP. "Slaves had to be guarded as to what they said because they would be punished if caught critiquing or offending the master class—thus they developed sophisticated forms of indirection and other forms of masking," Glenda Carpio, a professor of African and African-American studies at Harvard University, tells Breed and Italie.

While some critics have questioned the letter's authenticity, research reveals that Jourdon was very much a real person. Jason Kottke writes that a 1900 census lists a "Jordan Anderson" who was living in Ohio with his wife and three of their 11 children. According to a Dayton Daily Journal obituary that Kottke also discovered, Jourdon passed away in 1905 at age of 79.

"We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense," Jourdon writes. The full letter, which is well worth reading, is available at Letters of Note.