Five Epic Patent Wars That Don’t Involve Apple

The recent Apple patent decision was a big one, but here are some historical patent wars you might not have heard of

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201208270240075288349613_9475e73c09_b.jpg)

On Friday, a court awarded Apple $1.05 billion, ruling that Samsung had violated several of Apple’s patents. Both companies have their opinions about the case, and the net result will probably be an increase in prices for the consumer who will have to absorb licensing fees. But this is far from the first big patent case to get ugly. Here are some historical patent wars you might not have heard of.

The Wright Brothers v. Glenn Curtis

In 1906 the Wright Brothers were issued a patent for a flying machine. The patent included the steering system and the wing design. They then showed the patents and designs to Thomas Selfridge, a member of the Aerial Experiment Association established by Alexander Graham Bell in 1907.

The AEA then constructed several aircraft, including the Red Wing and the White Wing. Both looked a lot like the Wright’s patented designs. Glenn Curtis, a pilot, flew the White Wing 1,017 feet, which was far further than anyone had flown the plane before. Curtis then designed and piloted a plane called the June Bug, and in 1908 flew it 5,360 feet in one minute and forty seconds. The flight won him a prize offered by Scientific American to be the first plane to fly a kilometer in a straight line. A year later, Curtiss won another prize for flying 25 miles in a plane he designed. All of these planes used the same design the Wright’s had patented.

So the Wright’s finally sued Curtiss, claiming that he (and his company, the Herring-Curtiss Company) had stolen the Wright’s design. Then things got ugly. The U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission writes:

The battles that followed drained the financial resources of both parties with legal and court fees. Lawyers attempted to bring Curtiss and the Wrights together for an amicable settlement, but had no success. When Wilbur died of typhoid fever in 1912, the Wright family blamed Curtiss’ stubborn refusal to back down, claiming that Wilbur had lost his health over concern for the patent litigation.

The final verdict came in 1913. Orville Wright, now without Wilbur, was the unmistakable winner. All delays and appeals had been exhausted. The Federal Circuit Court of Appeals ordered Curtiss to cease making airplanes with two ailerons that operated simultaneously in opposite directions.

It didn’t end there either, it wasn’t until 1918, after World War I, that the suit was finally dropped.

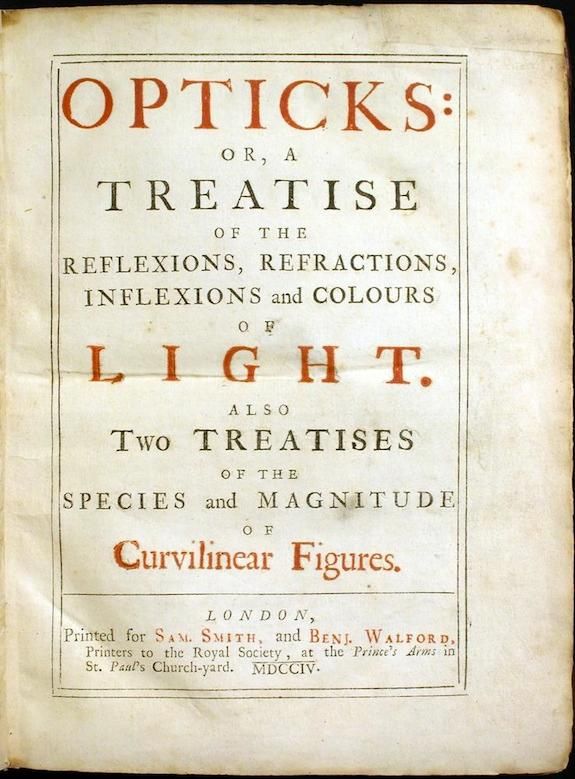

Isaac Newton v. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

This isn’t exactly a patent claim, since patents didn’t really exist during Newton’s time, but it is a claim on intellectual property. In the 18th century, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz invented calculus. He was the first one to publish papers on the topic, one in 1684 and one in 1686. But in 1704, Isaac Newton published a book called Optiks, claiming that he himself was the inventor of calculus. Of course, Leibniz wasn’t so happy about this. Smithsonian writes:

Newton claimed to have thought up the “science of fluxions,” as he called it, first. He apparently wrote about the branch of mathematics in 1665 and 1666, but only shared his work with a few colleagues. As the battle between the two intellectuals heated up, Newton accused Leibniz of plagiarizing one of these early circulating drafts. But Leibniz died in 1716 before anything was settled. Today, however, historians accept that Newton and Leibniz were co-inventors, having come to the idea independently of each other.

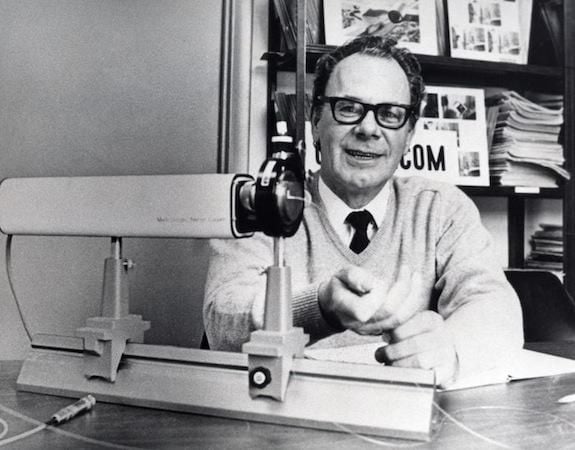

Gordon Gould v. the United States Patent and Trademark Office

In 1957, Gordon Gould invented the laser. He scribbled the idea into his notebook, writing, “Some rough calculations on the feasibility of a LASER: Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation,” and sketching out how he would make the beam. He even understood how important this idea might be, so he took it to a neighborhood store and had the notebook notarized. Three months later, two other physicists arrived at the same design.

Gould, who was a PhD student at Columbia at the time, thought that before he could patent his laser he had to build one that worked. So he dropped out of school and joined a company called Technical Research Group (TRG), convincing his new employer to fund and support his quest to build a working laser. They took on the project, but it was declared classified, and Gould – who had communist leanings – was banned from working on it. Regardless, Gould and TRG filed for a patent on the laser in April 1959. But a patent had already been requested for the same technology, by Schawlow and Townes, the two physicists who had figured out the laser three months after Gould. These other scientists were awarded their patent in 1960, leaving Gould and TRG to file a suit challenging those patents.

Fast forward thirty years, and Gould was still battling for his patents. In 1987, he started to win back several of his patents. All told, he was awarded 48 patents. Eighty percent of the proceeds of those patents were already signed away to pay for his thirty year court battle, but even with only a fraction of the profits left over he made several million dollars.

Kellogg Co v. National Biscuit Co.

Science and technology aren’t the only fields with epic patent battles, either. The fight extends into the kitchen, too. Early cereal makers fought over cereal design. Smithsonian writes:

In 1893, a man named Henry Perky began making a pillow-shaped cereal he called Shredded Whole Wheat. John Harvey Kellogg said that eating the cereal was like “eating a whisk broom,” and critics at the World Fair in Chicago in 1893 called it “shredded doormat.” But the product surprisingly took off. After Perky died in 1908 and his two patents, on the biscuits and the machinery that made them, expired in 1912, the Kellogg Company, then whistling a different tune, began selling a similar cereal. In 1930, the National Biscuit Company, a successor of Perky’s company, filed a lawsuit against the Kellogg Company, arguing that the new shredded wheat was a trademark violation and unfair competition. Kellogg, in turn, viewed the suit as an attempt on National Biscuit Company’s part to monopolize the shredded wheat market. In 1938, the case was brought to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the Kellogg Company on the grounds that the term “shredded wheat” was not trademarkable, and its pillow shape was functional and therefore able to be copied after the patent had expired.

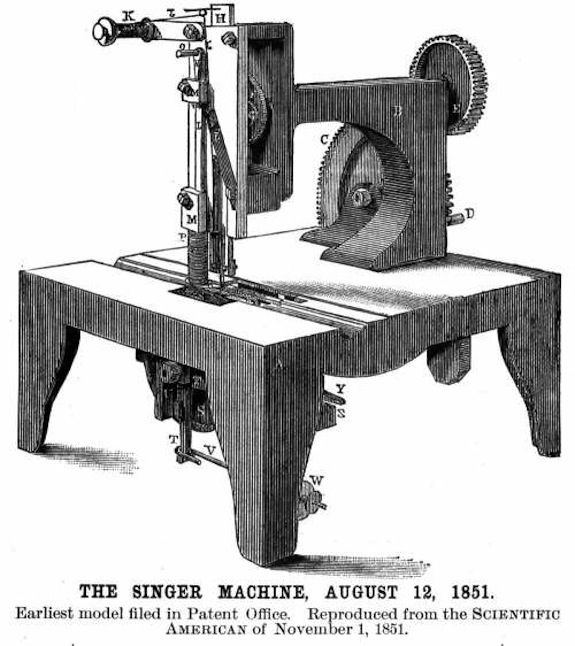

Howe v. Singer

In 1850, Elias Howe stared through a storefront window at a man operating a Singer Sewing Machine. He watched with interest – not because he wanted to buy the new machine – but because the machine seemed to be based off his own patents. Shortly after seeing the Singer machine, he sued Singer Sewing Machine and demanded a $2,000 royalty payment. The problem was that Singer hadn’t managed to sell any sewing machines yet, so they didn’t have any money to pay him. But when Howe returned a year later asking this time for $25,000, Singer had to actually deal with him. Singer’s attorney wrote, “Howe is a perfect humbug. He knows quite well he never invented anything of value.” They countersued, and the battle was on.

In what is now called “The Sewing Machine Wars,” Elias Howe and Isaac Singer faced off not just in the court room, but in the public eye as well. In 1853, the New York Daily Tribune ran these two advertisements on the same page:

The Sewing Machine-It has been recently decided by the United States Court that Elias Howe, Jr., of No. 305 Broadway, was the originator of the Sewing Machines now extensively used. Call at his office and see forty of them in constant use upon cloth, leather, etc., and judge for yourselves as to their practicality. Also see a certified copy, from the records of the United States Court, of the injunction against Singer’s machine (so called) which is conclusive …. You that want sewing machines, be cautious how you purchase them of others than him or those licensed under him, else the law will compel you to pay twice over.”

Sewing Machines-For the last two years Elias Howe, Jr., of Massachusetts, has been threatening suits and injunctions against all the world who make, use or sell Sewing Machines …. We have sold many machines-are selling them rapidly, and have good right to sell them. The public do not acknowledge Mr. Howe’s pretensions, and for the best reasons. 1. Machines made according to Howe’s patent are of no practical use. He tried several years without being able to introduce one. 2. It is notorious, especially in New-York, that Howe was not the original inventor of the machine combining the needle and shuttle, and that his claim to that is not valid … Finally-We make and sell the best SEWING MACHINES.

The Sewing Machine Wars are particularly interesting for their parallel to modern patent issues. Adam Mossof writes:

Howe was a non-practicing entity, i.e., a patent-owner who is not actively commercializing his own intellectual property. In modern parlance, Howe was a “patent troll.”

In the end, Singer settled with Howe for $15,000. But the Sewing Machine War wasn’t over. Instead, it sparked an eruption of litigation among sewing machine companies all over the United States.

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)