The First Photos of Free-Falling Snowflakes Reveal Their Imperfections

Collisions in mid-air often produce ice crystal aggregates, rather than single symmetrical flakes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/76/e27602dd-01d2-42c5-9060-24fa25975bea/snowfallaggregate2.jpg)

It took Wilson Bentley, a self-educated farmer in Vermont, years to figure out how to do it, but his patience paid off with the first photograph of a single snowflake in 1885. Bentley united a microscope with an early camera to capture the crystal’s six-sided intricacy. It was just the first of more than 5,000 such images he would collect in his lifetime—work that gave us the idea that "no two snowflakes are exactly alike."

Since then, whether driven by curiosity or science, people have tried to capture even better photos of the most enchanting form of winter precipitation. Provided that your appetite for snow hasn’t been throughly satiated this winter, the latest effort is worth a gander.

Recently, the National Science Foundation funded a project to capture images of snowflakes as they fall. In the hands of University of Utah engineer Cale Fallgatter and atmospheric scientist Tim Garrett, a high-speed camera reveals something slightly different than beautiful uniqueness, reports EarthSky.

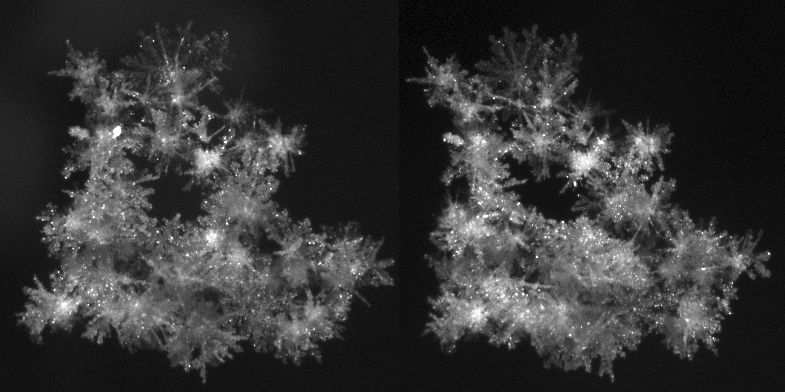

[M]ost of the snowflakes you see in softly falling snow aren’t single perfect ones. Fallgatter and Garrett’s camera showed most are aggregates of several snowflakes, which collided and stuck together during their fall from a cloud to Earth.

With two cameras, the researchers can even create stereoscopic images. NSF explains that if you look at the center of the image below, unfocus your eyes and find the right distance from the screen (a process similar to a "Magic Eye trick") the images merge and pop into 3D.

The next camera the researchers are working on will be a cheaper, hardier version that could actually help keep drivers safe. "Right now the problem in the transportation safety sector is to understand exactly what's falling out of the sky," says engineer Cale Fallgatter in an NSF statement. "Our goal was to come up with a game-changing instrument based on new technology to compete with what is currently out there."

Precipitation falling right at the freezing point is particularly difficult to classify—and also to determine what driving conditions will be like. Better pictures of falling precipitation will help make the road safer.

Plus, while the photos aren’t as perfect as Bentley’s (and some now suspect that he altered photo negatives to emphasize the flakes’ symmetry), they are still beautiful.