The First Artificial Skating Rinks Looked Pretty But Smelled Terrible

Before the technology to reliably freeze water existed, the first rinks used pig fat and salts

:focal(323x275:324x276)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/fa/a3fa1f1e-3fa8-44d1-8dd4-a98ccf1700c7/glaciarium_ice_rink1976.jpg)

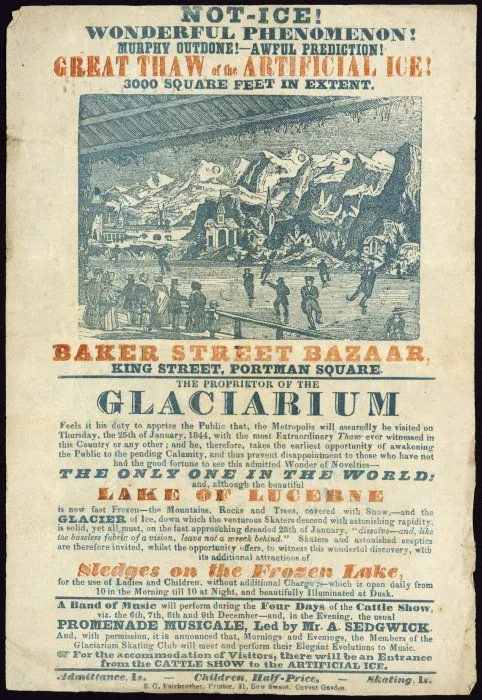

Skating rinks can be blissful. And images of the Glaciarium, the world’s first permanent artificial ice rink, seem no different. Skaters glide by on the frozen pond moving to the tunes of a live band. But images can't capture the rink's fatal flaw: it smelled.

The Glaciarium opened to the public in June 1844—hardly a month when people of the age normally engaged in “the graceful and manly pastime of skating,” as the journal Littel’s Living Age put it at the time. The rink was also pretty. According to the journal, “[i]t represents a lake imbedded amid Alpine scenery, with snow-covered mountains and precipitous glaciers, the judicious management of the light giving everything a cold and wintry appearance.” Mounds of “snow” surrounded the “lake.”

But, as Tim Jepson and Larry Porges write in the National Geographic London Book of Lists, it smelled noxious. “At the time, ice couldn’t be manufactured and kept frozen in sufficient quantities to create a proper rink. The appalling smell of the substitute, a mixture of pig fat and salts, would be the project’s undoing,” they write.

The Glaciarium was originally a Covent Garden spectacle, according to author Julian Walker, opening in the public market in January before moving to a more permanent location in June. “Entry cost one shilling,” writes Walker, “with skating an extra shilling.”

The novelty wore off as skaters tired of the smell, writes Zoe Craig for Londonist, and the Glaciarium closed before the year was out.

Though the original didn’t hang around for long, write Jepson and Porges, technology continued to develop and the idea of an artificial skating rink wasn’t forgotten. "By January 1876... refrigeration technology was such that John Gamgee was able to open the world’s first mechanically frozen rink in a tent just off King’s Road," they write.

Gamgee was an inventor and veterinarian. Like many others at the time, he was working on the problem of how to freeze meat for long-distance transport, Jepson and Porges write. What he developed, however, allowed him to build a better ice rink.

“Gamgee’s rink was based on a concrete surface, with layers of earth, cow hair and timber planks,” Craig writes. Atop this substrate sandwich ran copper pipes that carried Gamgee’s special solution of glycerine, ether, nitrogen peroxide and water. Water was poured over the pipes and, similar to how modern refrigeration works, the solution pumped through the pipes froze the surrounding liquid.

Gamgee’s rink was members only, Craig writes, and when it became established on King’s Road he added touches to appeal to his rich clients. These included an orchestra gallery and images of the Alps—similar to the original Glaciarium.

But there was a problem with this new technology, writes Craig, it worked too well. “The ice was just too cold,” she writes: “the intense chill meant skaters had to deal with a thick mist rising off the surface of the rink.”

But skaters were more willing to battle the mist than they were the stench. Gamgee's ice rinks hung around for at least a decade, writes Craig, giving way to the modern ice rink that brings year-round winter fun to people worldwide.