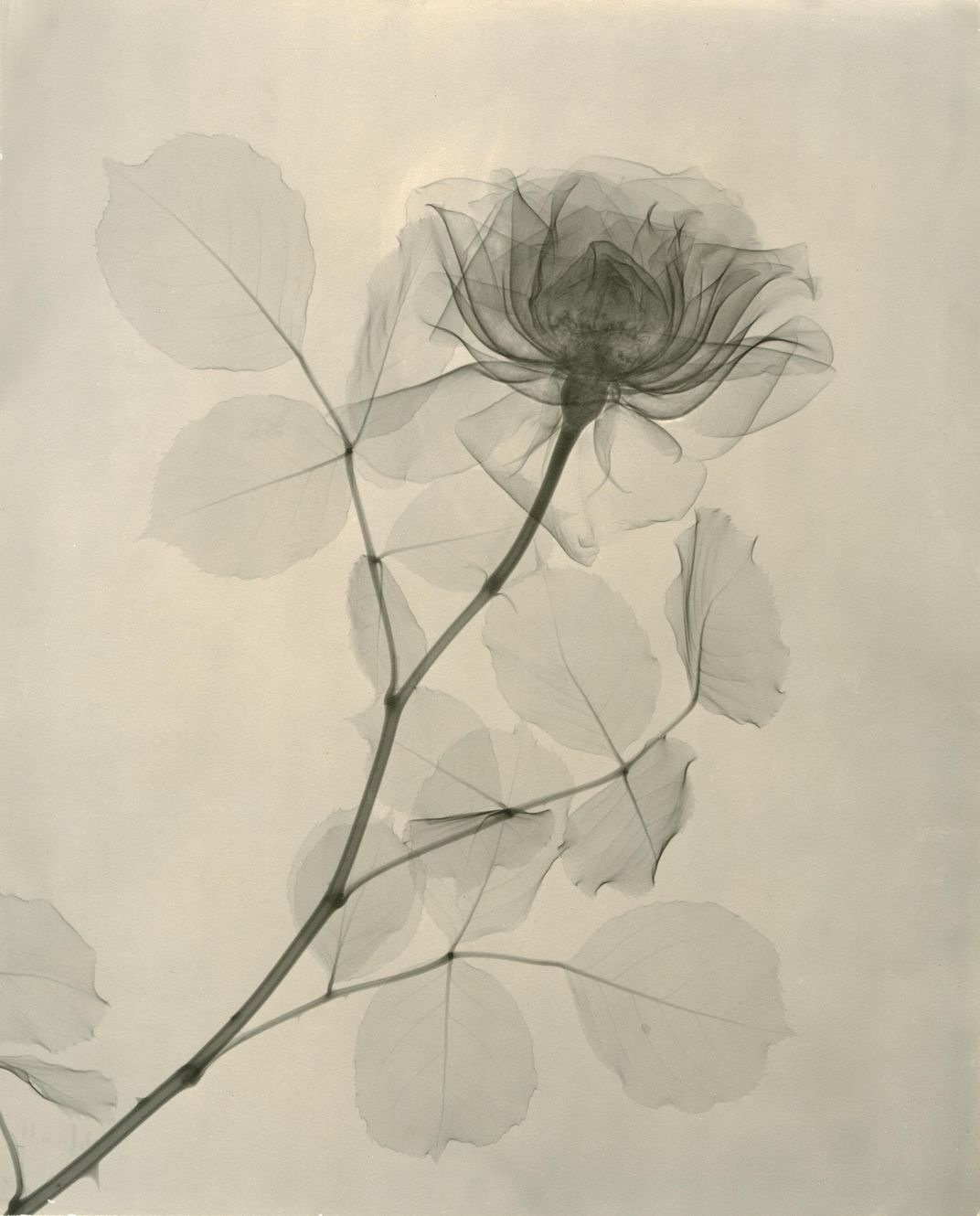

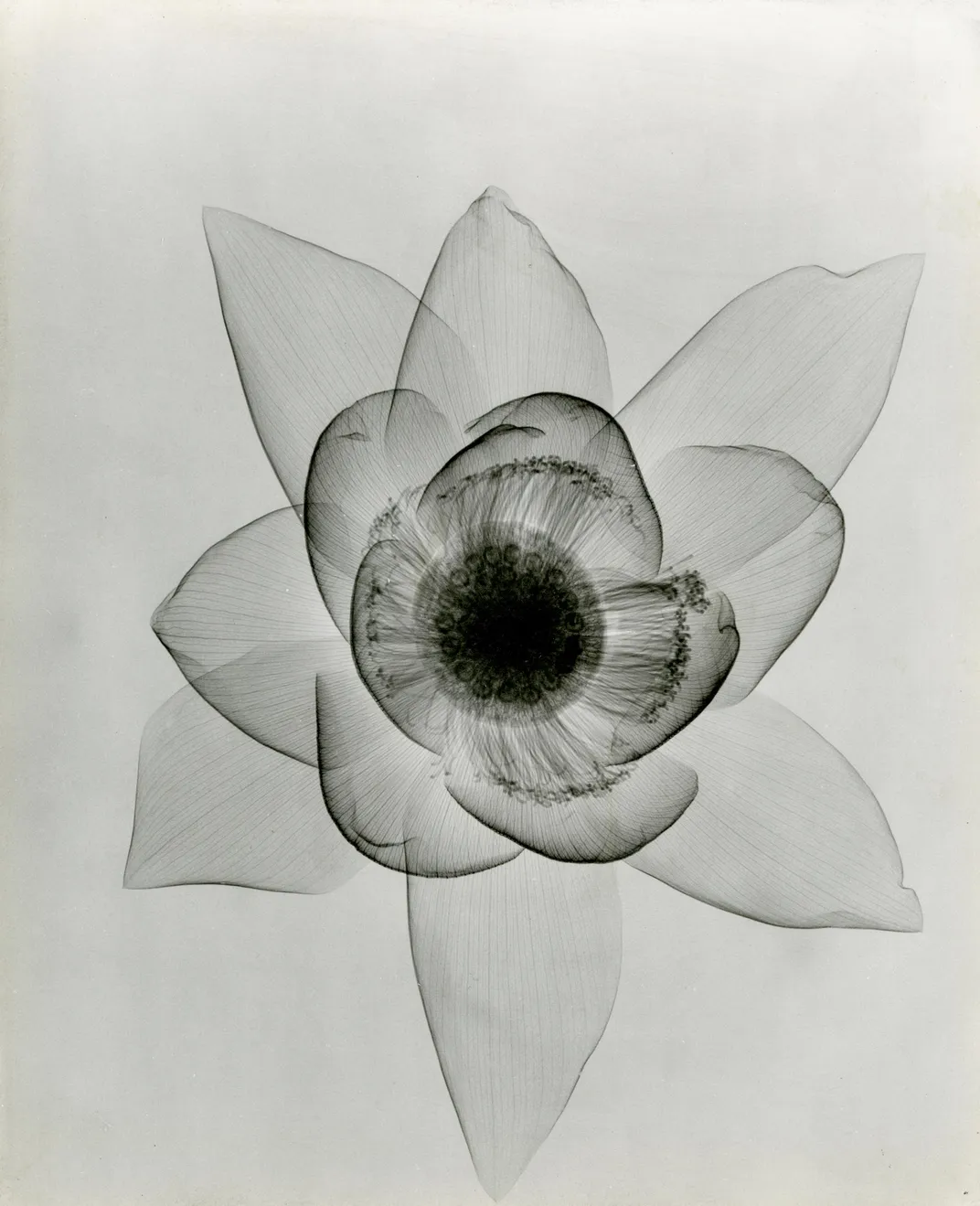

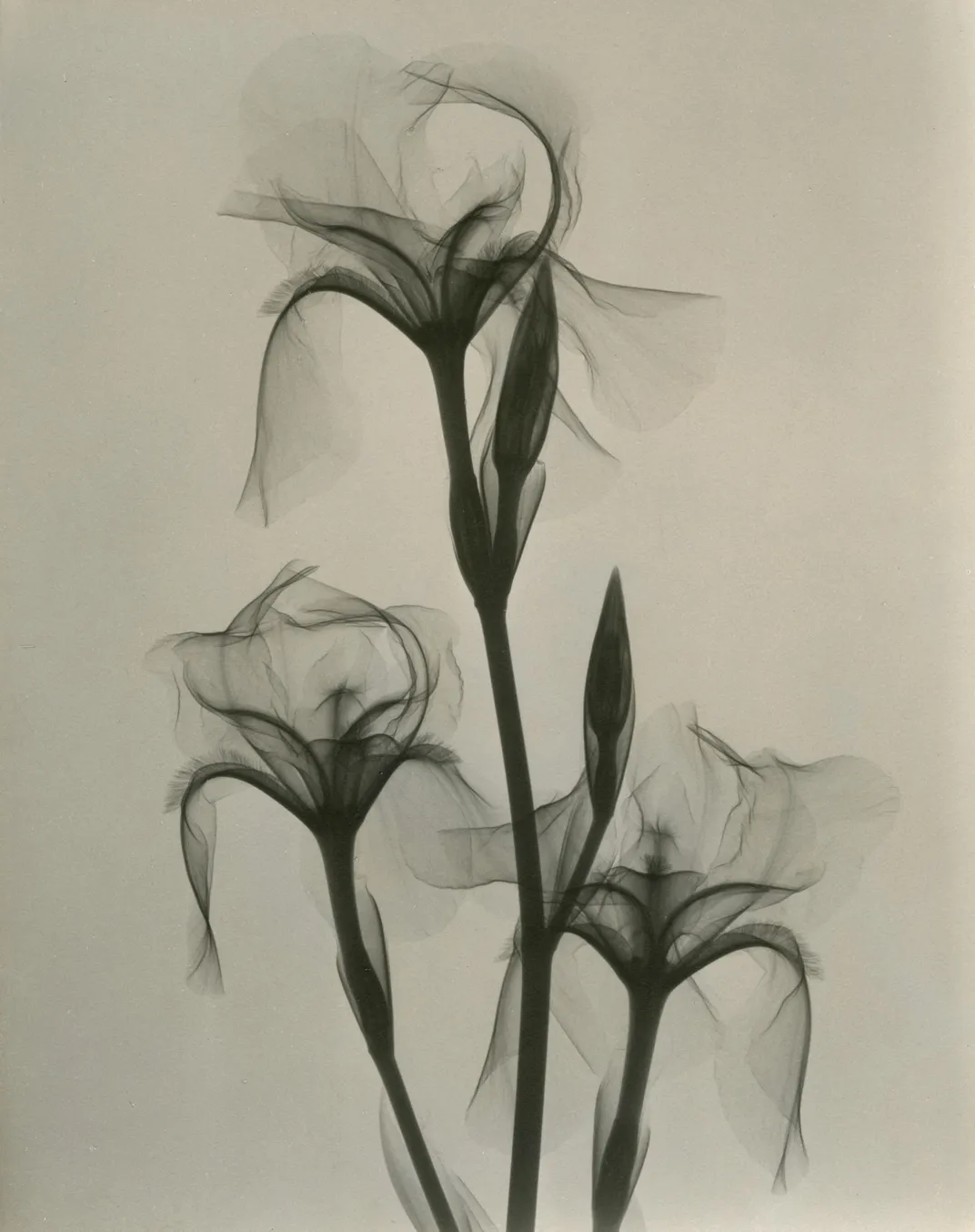

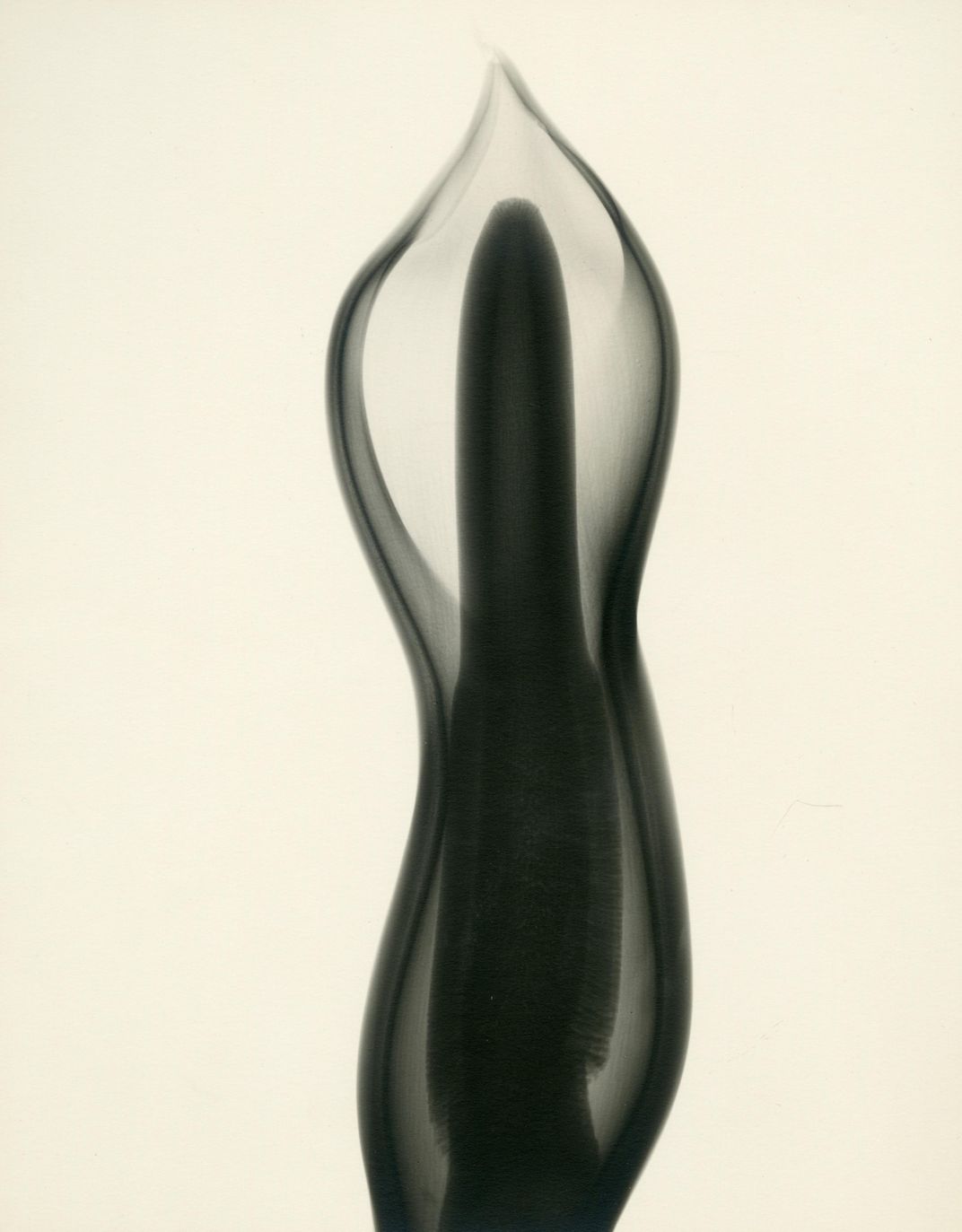

Check Out These X-Rays of Flowers From the 1930s

Dain L. Tasker’s radiographs depict delicate flowers from the inside out

More often than not, x-rays are a medical tool used to take a peek inside a body and see if everything’s in the right place. But during the 1930s, one doctor turned his x-ray machine to another subject: the anatomy of flowers. Now, a collection of Dain L. Tasker’s x-ray images of flowers are on display in an exhibit called “Floral Studies” at the Joseph Bellows Gallery in La Jolla, California.

When most people think of x-rays, they probably imagine sitting or standing in a hospital rooms in front of a strange-looking machine. However, at it’s core, an x-ray machine is really just a big camera—albeit one that takes photographs using radiation. Back in the 1930s, x-rays were still a pretty new technology when Tasker, then the head radiologist at Los Angeles’ Wilshire Hospital, turned the machine on one of his favorite subjects: flowers.

“Flowers are the expression of the love life of plants,” Tasker wrote of his work.

Tasker had been an amateur photographer for years, but didn’t connect his hobby to his day job until some time during the 1930s, when he began capturing images on x-ray film. After experimenting with self-portraits, Tasker turned to flowers, often framing a single flower and focusing on their internal structures and anatomy instead of trying to capture whole bouquets, Kate Sierzputowski writes for Colossal. As a result, his images often appear almost as translucent, minimalist ink drawings instead of photographs.

Operating an x-ray machine isn’t something most people know how to do, but apparently Tasker didn’t struggle too much in taking his radiographs, noting that it just takes “an abiding patience” and an understanding of “flowers and their habits,” Claire Voon writes for Hyperallergic.

But when he wanted to start making prints of his x-rays, Tasker reached out to photographer Will Connell, who was then teaching at Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design. Connell not only helped Tasker print his pictures, but helped him to exhibit his work in photography shows. Eventually, Tasker’s radiographs were published in national magazines—yet he still gave out prints to his nursing students when they graduated their program.

Over the years, x-rays outside of a medical context became more common, as archaeologists and some museums often use them to take images of the insides of objects without damaging them. During the 1950s, Soviet teenagers would also repurpose medical x-rays to make bootleg copies of records smuggled in from the West. But Tasker was one of the first radiologists to see that x-rays weren’t just a medical tool. They could also be used for art.

“Floral Studies” is on display at Joseph Bellows Gallery in La Jolla, California through February 19, 2016.