Channel Childhoods Gone By With This Digital Archive of Victorian Children’s Books

From nursery rhymes to religious lectures, this digital archive shows how kids read in a bygone age

Once upon a time, children didn’t have a literature of their own. Terms like “middle grade” and “picture book” were unheard of, and the majority of books owned by American households were religious in nature and too pricy to collect. But then, an evolving idea of childhood and cheaper printing technology paved the way for something wonderful—children’s books. As Josh Jones notes for Open Culture, over 6,000 of those books are available in a digital archive that captures the essence of 19th-century childhood.

It’s called the Baldwin Library of Historical Literature, and it features thousands of digitized children’s books from the archives of the University of Florida’s library collections. The broader Baldwin collection contains books from the 1600s to the present day, but the selection of 6,092 digitized books focuses on juvenile fiction from the 19th century.

It was a revolutionary time for reading. In an era long before Little House on the Prairie or Goodnight Moon, children weren’t considered a viable reading audience. On the one hand, it makes plenty of sense: Twenty percent of white Americans 14 years or older were unable to read in 1870. For poor and diverse populations like African-American people, who were denied educational opportunities and discouraged from becoming literate at all, the number was even lower—79.9 percent of African-American adults or those identified as "other" could not read in 1870. Those numbers only started to drop in the early 20th century when concerted literacy efforts and more widespread compulsory education initiatives exposed both children and adults to literacy skills.

But lack of literacy wasn’t the only reason children’s books didn’t come into vogue until relatively late in the history of reading. The concept of childhood as we know it simply didn’t exist in colonial America, where kids were expected to work alongside adults and adhere to strict discipline rather than spend their time being children. Only with the growth of Romanticism and the spread of the middle class did childhood—a fleeting time for play, imagination and youth—become a thing. And even as a romanticized ideal of childhood spread, many children played a vital role in their family economies and worked just as hard as their parents.

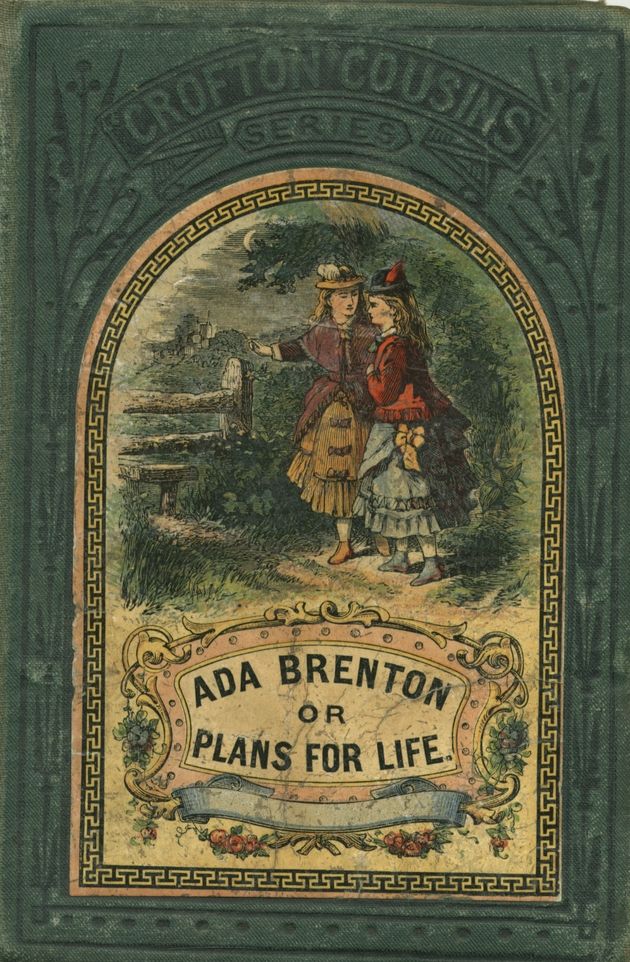

The books in the Baldwin’s collection spread ideas and ideals of childhood even as they entertained kids who were lucky enough to be able to read and afford them. They show off attitudes about kids that might seem foreign today. In the book Ada Brenton, or Plans for Life, published around 1879, for example, the heroine spends pages stressing about the most improving course of reading she can undertake. The 1851 book The Babes in the Wood features ballads and poems about orphaned children who trying to escape the clutches of an uncle who wants to sell them (spoiler alert: they die in each other’s arms). And Harry Hardheart and His Dog Driver, an 1870s book by the American Tract Society, tells the tale of a wicked boy who tries to drown his own dog but is then saved by the dog he’s trying to kill (and a long lecture).

Eventually, children's books became more sophisticated. During the 1930s and 1940s, children's publishing entered its golden age, with publishing houses investing more money in developing new talent and legendary editors like Ursula Nordstrom helping shepherd some of history's most classic children's books (think: Where the Wild Things Are and Harriet the Spy) into publication. Today, juvenile readers are a bona fide market force, buying more books than adults and clamoring for books that are more innovative and diverse.

The books of the 19th century may seem odd or harsh by today’s standards, but their mere existence—books intended for an audience of young readers—was a revelation. And don’t worry: The Baldwin’s collection contains more than scary tracts or morality tales. The digitized collection has everything from a special subsite devoted to Alice In Wonderland to classics like Black Beauty, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Grimm’s Fairy Tales to lesser-known books by the likes of authors like Louisa May Alcott.

Childhood may have changed a lot since the 19th century, but one thing hasn’t: the impulse to cuddle up and read a good book.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)