Better, Faster, Taller – How Big can Buildings Really Get?

The race for the tallest structure in the world has been with us since humans built structures, and today it is going strong. But where’s the limit?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120820102008towers.jpg)

In four years, Saudi Arabia plans to have a tower that’s 1,000 meters high. To put that into perspective, the Empire State Building is 381 meters. The race for the tallest structure in the world has been with us since humans built structures, and today it is going strong, sending tall spindly spires upwards.

But the Atlantic Cities asks the real question: when does it stop? How tall can we get? They write:

Ask a building professional or skyscraper expert and they’ll tell you there are many limitations that stop towers from rising ever-higher. Materials, physical human comfort, elevator technology and, most importantly, money all play a role in determining how tall a building can or can’t go.

It’s somewhat reminiscent of the story of the Tower of Babel. Humans decided to build a tower up to heaven. When God saw what they were up to, he realized that he had to stop them. To do so, he spread them across the Earth and gave them all different languages so they couldn’t communicate with one another. Archaeologically, the tower from the story in the Bible was probably the Great Ziggurat of Babylon from 610 BC, which stood 91 meters high.

The skyscrapers of today are tall for a quite different reason than the first skyscrapers ever built (although compared to today’s towers, early skyscrapers are minute). Forbes explains:

One of the first skyscrapers was designed and built by Bradford Lee Gilbert in 1887. It was designed to solve a problem of extremely limited space resulting from the ownership of an awkwardly shaped plot of land on Broadway in New York City. Gilbert chose to maximize the value (and potential occupancy) of the small plot by building vertically. His 160-foot structure was ridiculed in the press, with journalists hypothesizing that it might fall over in a strong wind. Friends, lawyers and even structural engineers firmly discouraged the idea, warning that if the building did fall over, the legal bills alone would ruin him. To overcome the skepticism of both the press and his advisors, Gilbert took the top two floors for his personal offices. From then on, the skyscraper has been a symbol of economic and financial success, the mark of one’s ascent.

Today, these monster buildings do actually have many of the same problems that Gilberts critics cited. And the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat recently asked the world’s leading skyscraper architects just when, and why, skyscraper madness would have to stop. Their answers are in this video.

The man behind the soon-to-be tallest tower, Adrian Smith, says in the video that elevators are the real issue. William Backer, the lead structural engineer at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, on of the world’s leading skyscraping firms, says the limit is far beyond our current structures. “We could easily do a kilometer. We could easily do a mile,” he says in the video. “We could do at least a mile and probably quite a bit more.”

The video also features Tim Johnson, chairman of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. The Atlantic Cities:

For a Middle East-based client he’s not allowed to identify, Johnson worked on a project back in the late 2000s designing a building that would have been a mile-and-a-half tall, with 500 stories. Somewhat of a theoretical practice, the design team identified between 8 and 10 inventions that would have had to take place to build a building that tall. Not innovations, Johnson says, but inventions, as in completely new technologies and materials. “One of the client’s requirements was to push human ingenuity,” he says. Consider them pushed.

These buildings are so tall, that in the 1990′s, when a 4,000 meter tower was proposed in Tokyo, they called it a “skypenetrator” rather than a skyscraper. That tower would have been 225 meters taller than Mount Fuji. That’s right, taller than mountains. But could we really, actually, build buildings taller than, say, Mount Everest? Based on Baker’s calculations, a building that was 8, 849 meters tall (one meter taller than Everest) would need a base of about 4,100 square kilometers. Possible? Baker says so. The Atlantic:

And this theoretical tallest building could probably go even taller than 8,849 meters, Baker says, because buildings are far lighter than solid mountains. The Burj Khalifa, he estimates, is about 15 percent structure and 85 percent air. Based on some quick math, if a building is only 15 percent as heavy as a solid object, it could be 6.6667 times taller and weigh the same as that solid object. A building could, hypothetically, climb to nearly 59,000 meters without outweighing Mount Everest or crushing the very earth below. Right?

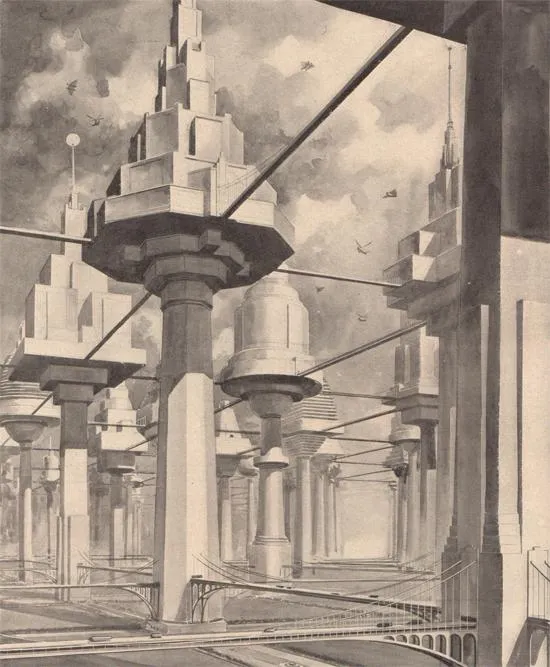

Perhaps the real question is, do we want a tower taller than Mount Everest? People have worried about the rise of skyscrapers since the Biblical Tower of Babel. In New York City, during the skyscraper boom, some architects worried that the gigantic buildings would deprive New Yorkers of sunlight. In 1934, Popular Science printed an illustration showing future cities constructed like trees to let light in.

The design came from R.H. Wilenski depicts skyscrapers in a quite different way than we see them now. Rather than broad at the base and spindly at the top, these have long, skinny trunks topped with a building’s base. But many of the challenges in building our modern elevators, and these hypothetical tree buildings, remain the same. Popular Science wrote:

The scheme leaves the ground level virtually unobstructed. Each building is supported upon a single, stalk-like shaft of steel or strong, light alloys, resting in turn upon a massive subterranean foundation. Modern advances in the design of high-speed elevators simplify the problems of transporting passengers between the buildings and the earth. Access from one building to another is provided by a system of suspension bridges, and stores and places of recreation contained in the building make it possible to dwell aloft for an indefinite time without needing to descend. Gigantic, luminous globes are placed at strategic points to light the aerial city by night, while by day the inhabitants enjoy the unfiltered sunshine and fresh air of their lofty nests.

No matter their shape, the world can be pretty certain of one thing. Skyscrapers are going to keep getting bigger for a long time coming. Here’s a graphic of about 200 high rises that are on hold right now. And in there are almost certainly more to come.

More at Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)