Barnes Foundation Launches Digital Gallery of Its Amazing Art Collection

Historically infamous for being inaccessible to the public, the foundation has now published images of almost half of its collection online

Any long-time observers of the art world will be flabbergasted by the latest new out of Philadelphia: art housed at the Barnes Foundation has been upgraded to high-res, downloadable images as part of an Open Access program, reports Sarah Cascone at artnet News.

That’s surprising because the original owner of the collection, Albert C. Barnes, left very explicit instructions about how his world-class collection was to be presented to the public after his death, and he forbade any of the images from being reproduced in color.

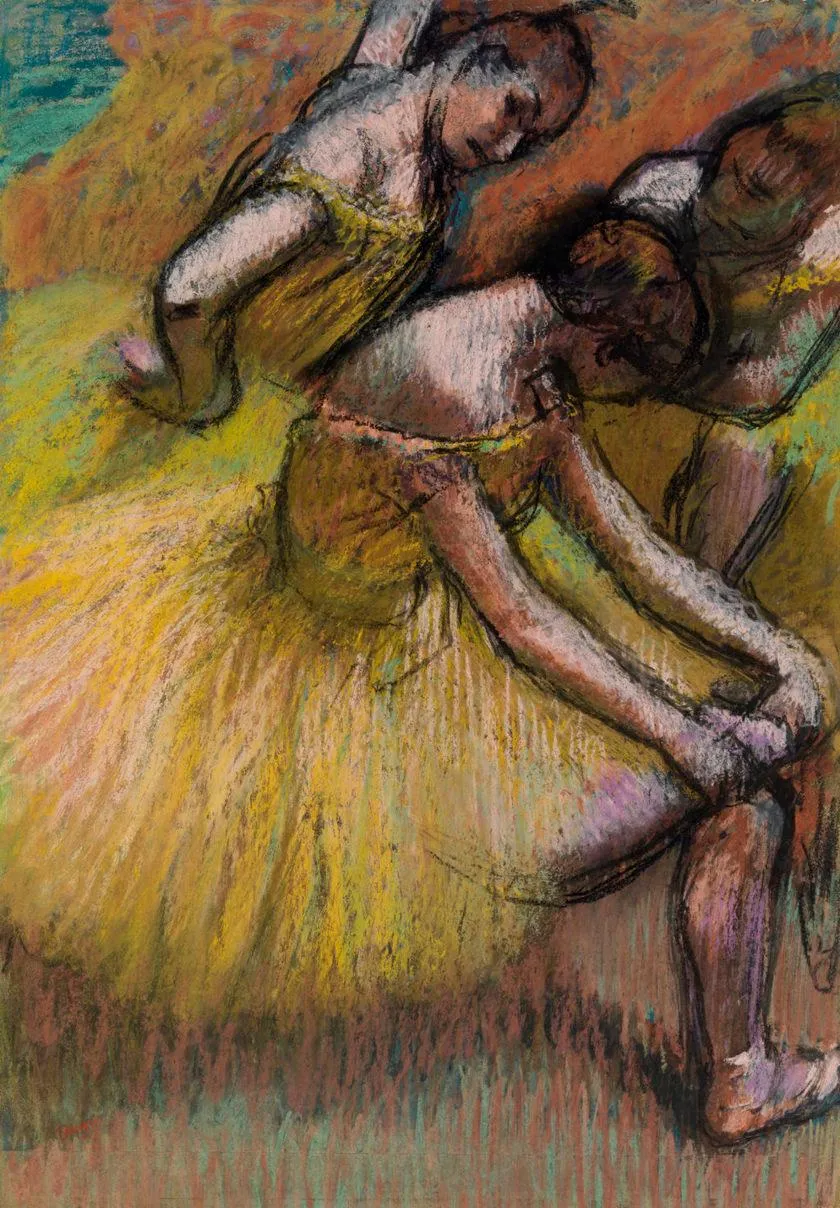

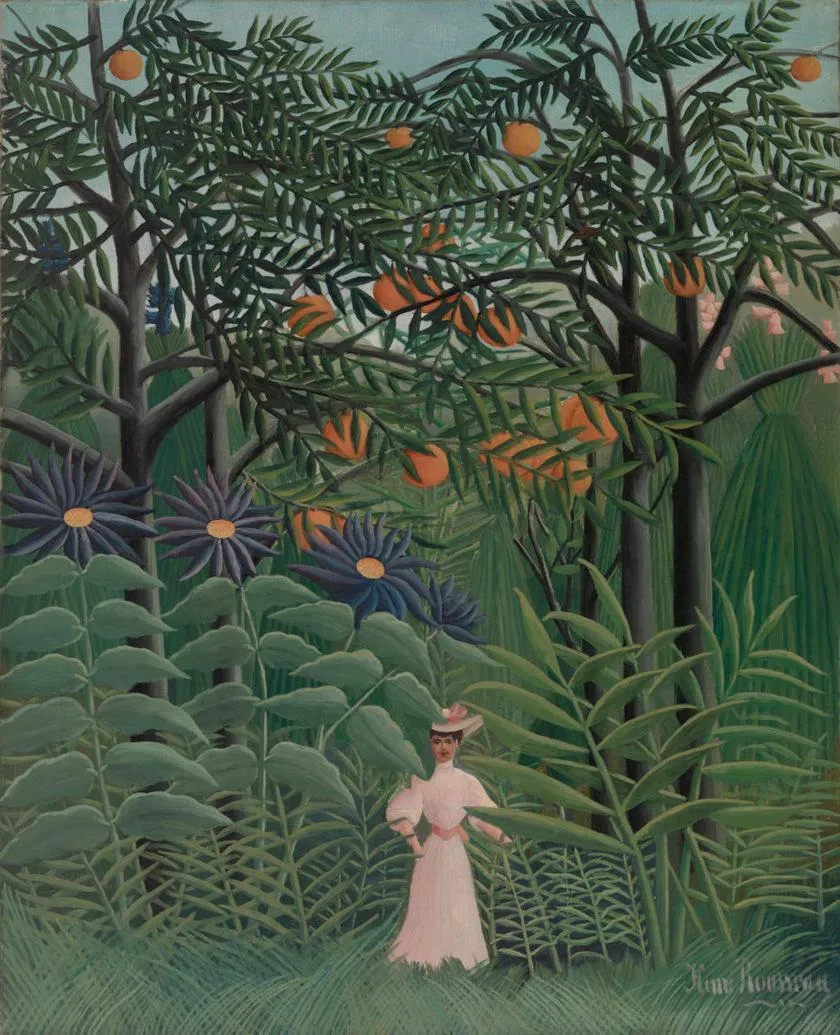

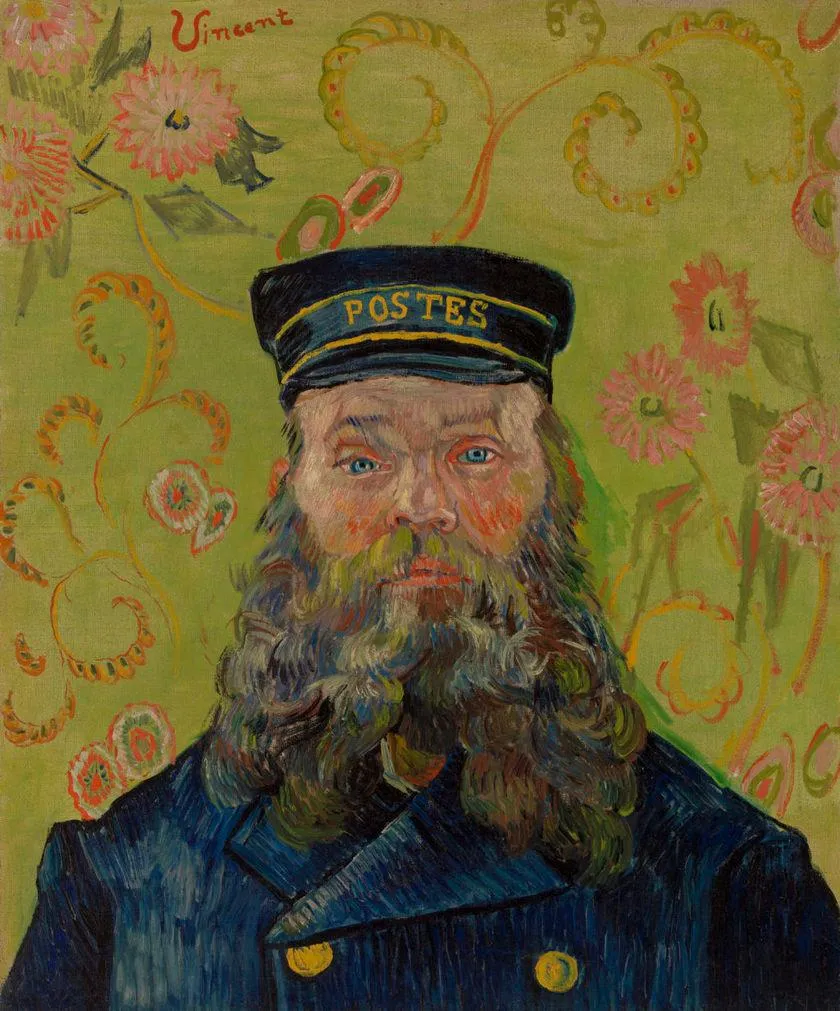

The Barnes Collection is considered one of the greatest galleries of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and Early Modern art in the world. Barnes had a knack for picking winners, and between 1912 and 1951, he amassed a vast collection of works by Renoir, Cezanne, Matisse, Degas, Picasso, Modigliani and many other notables. In 1925, he opened a gallery designed by architect Philippe Cret in Merion, Pennsylvania, to display his work.

In Merion, the public was allowed limited access to view the collection, but, because the Foundation was chartered as a school, its art students were granted greater access. Due to Barnes's stipulations, the collection could not be loaned, moved, sold or reproduced. After Barnes death, his wishes were more or less followed, with attendance to the gallery capped at 60,000 per year. But by 2002, the Foundation had become "financially beleaguered" in the words of Ralph Blumenthal of the New York Times, and had accepted funding from Philadelphia foundations. Philip Kennicott of the Washington Post reported that the foundations gave with a stipulation: "that the collection be made more accessible to the public."

In order to honor that condition, the Foundation announced that it would be moving its hefty collection to a new facility in downtown Philadelphia; a 2009 documentary, The Art of the Steal documents the drama and controversy surrounding the decision. In 2012, the museum debuted on Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway, presenting itself as a more modern, spacious replica of the Barnes Merrion gallery, down to replicating the original positionings of the paintings on the walls.

While the online publication of the works may seem to critics like a continuing erosion of Barnes's vision for his collection, in a blog post, the museum explains that Barnes was not against publishing images from his collection in color, per se. He just thought that the reproductions of his day were very poor. Barnes archivist Barbara Beaucar explains:

The Barnes Foundation always allowed the reproduction of its art works in black and white. The great bugaboo that Dr. Barnes had was with color reproduction. In 1941, he gave Angelo Pinto permission to photograph the gallery in color. These images are most likely those that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in 1942 and they appear garish–a result of the four color separation process that was used in magazine and newspaper reproduction.

It appeared that Dr. Barnes was not so much against color photography, but felt that the methods of reproduction of color photographs were not advanced enough. This is likely why Miss de Mazia did not allow any color reproduction of the collection in publications.

We believe that the 1995 publication, Great French Paintings From The Barnes Foundation: Impressionist, Post-impressionist, and Early Modern, was the first publication to include works in color.

The museum adds that the online gallery is a chance to pull the collection into the 21st century and finally educate the public about the incredible collection and its masterpieces. Some 2,081 of the foundation's 4,021 pieces will be digitized. While paintings in the public domain can be downloaded and shared from the museum site, those still under copyright have some lower resolution and cannot be downloaded.

Michele Debczak at Mental Floss reports that similar open access projects at other art museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, The Getty Museum and Metropolitan Museum, also influenced the foundation's decision. Whatever the politics or controversies behind the move, having the images online is undeniably something to celebrate.