Artifacts Found in Indonesian Cave Show Complexities of Ice Age Culture

Pendants and buttons as well as carvings suggest the inhabitants of Wallacea were as advanced as Europeans during the Ice Age

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/be/dcbe0981-183a-4f98-b007-6fd379a0917b/pendant.jpg)

The archaeological record of modern humans living in the island chain known as Wallacea, which covers portions of modern-day Indonesia, is sparse. Of the 2,000 small islands considered part of Wallacea, many of which were inhabitable, Charles Q. Choi at LiveScience reports that just a few sites on seven of the islands have been studied. So, perhaps it's not surprising that recent discoveries, including newly discovered cultural artifacts dating from 30,000 to 22,000 years ago, are upending notions about Wallacea's early inhabitants.

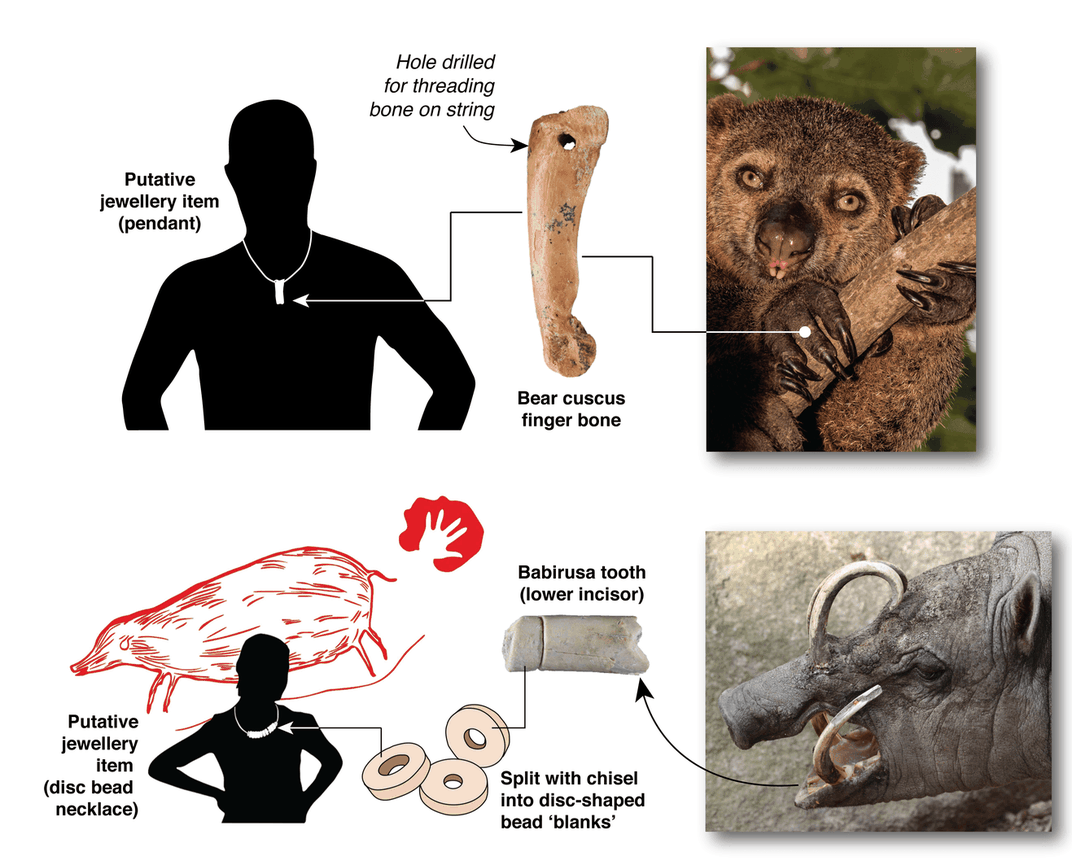

According to a press release, in a cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, researchers uncovered beads made from the tusks of pig-like babirusas and a pendant made from the finger bone of a bear cuscus, a type of marsupial that lives in trees. The archaeologists also found stones cut with geometric patterns and hollow animal bones with traces of ochre on them that could have been used to blow the pigment on rocks to create art.

“The discovery is important because it challenges the long-standing view that hunter-gatherer communities in the Pleistocene tropics of Southeast Asia were less advanced than their counterparts in Upper Paleolithic Europe, long seen as the birthplace of modern human culture," Adam Brumm, archaeologist at Australia’s Griffith University and co-author of a paper on the find in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, tells Choi.

Alice Klein at New Scientist reports that the team decided to excavate the shelter because other signs of early cultural sophistication were found in the area in 2014 including a 40,000-year-old hand stencil and a 35,000-year-old depiction of a babirusa. The new artifacts are building a new narrative about the first peoples to move into the region. “The idea that complex, figurative behaviors did not exist in Wallacea and Australia at this time is just not true,” Peter Veth, an archaeologist at the University of Western Australia who was not involved in the study, tells Klein. “It’s exciting that we’re now filling in the gaps.”

While the research shows the sophistication of the people moving into the area, the researchers also say it shows that moving into new areas and encountering news species also changed the way early humans looked at the world and influenced their spiritual practices. “The discovery of ornaments manufactured from the bones and teeth of two of Sulawesi's flagship endemics—babirusas and bear cuscuses—and a previously recorded painting of a babirusa dated to at least 35,400 years ago, shows that humans were drawn to these dramatically new faunal species,” Brumm says in the press release. “This may indicate that the conceptual world of these people changed to incorporate exotic animals.”

In fact, Brumm and paper co-author Michelle Langley note over at The Conversation that there were very few babirusa bones among the thousands of animal bones found in the cave, showing that the people likely did not often eat the species and had some sort of reverence for the beast. The researchers think that the complex interactions of people in Wallacea with new species may show that the strong spiritual relationships indigenous people in Australia have with certain animals may have begun before their ancestors even reached the continent, migrating from Eurasia, through Wallacea to Australia.