An Archive of Native Americans Portraits Taken a Century Ago Spurs Further Exploration

Edward S. Curtis’ photography is famous, but contemporary Native American artists go beyond stereotypes

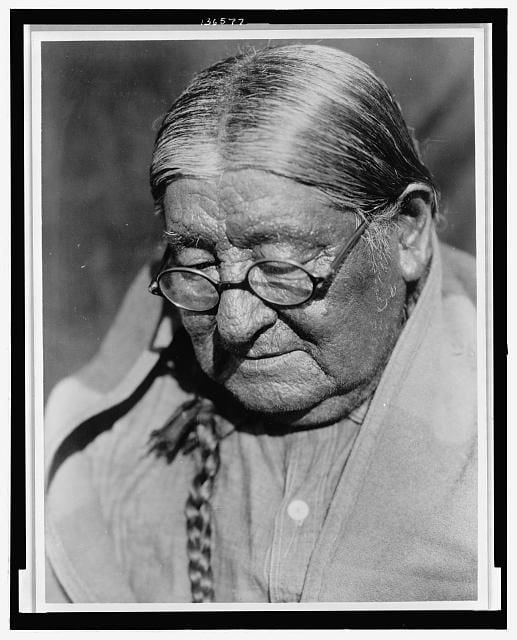

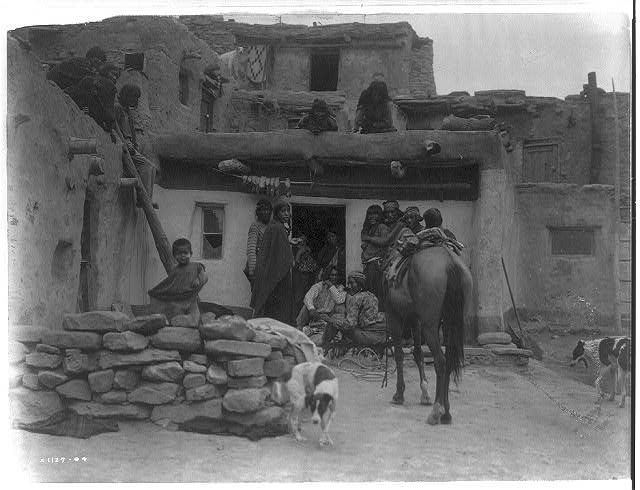

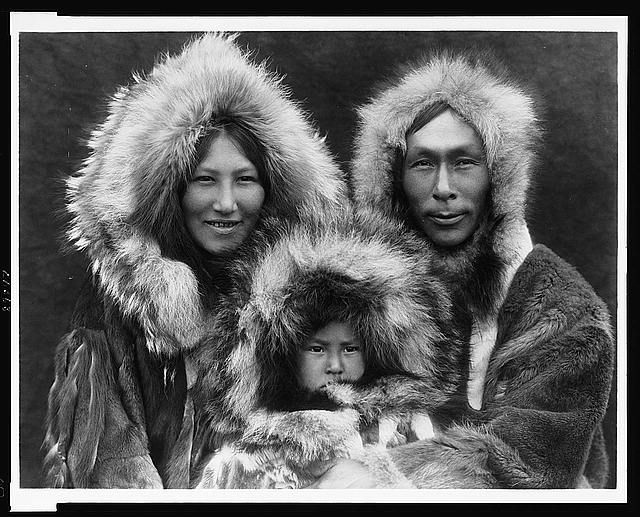

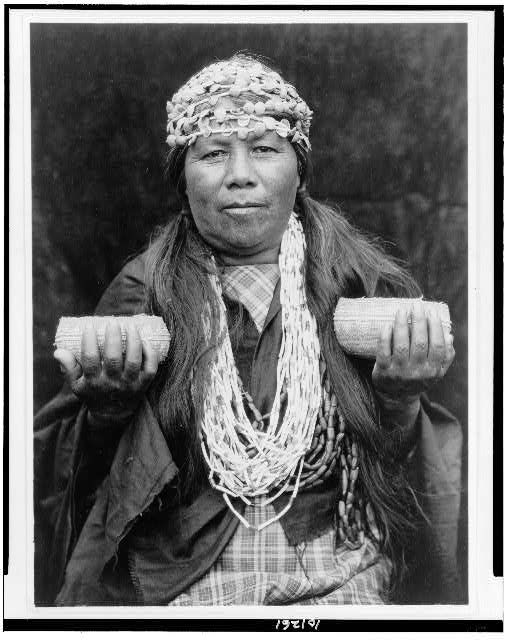

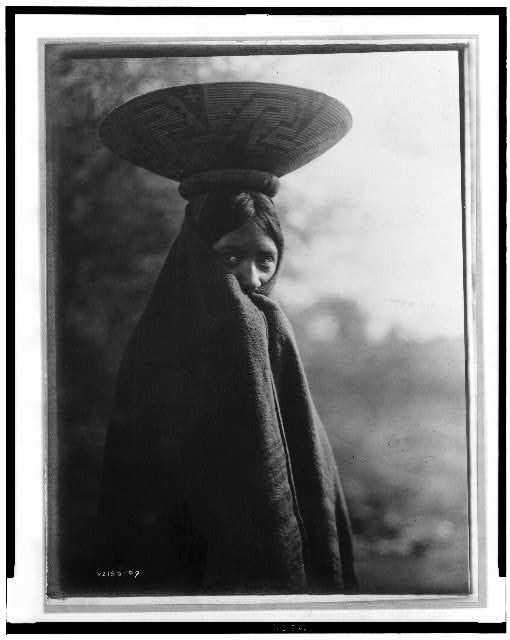

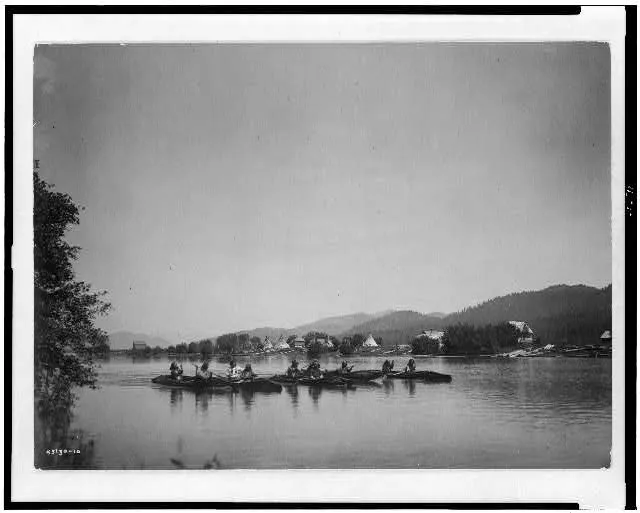

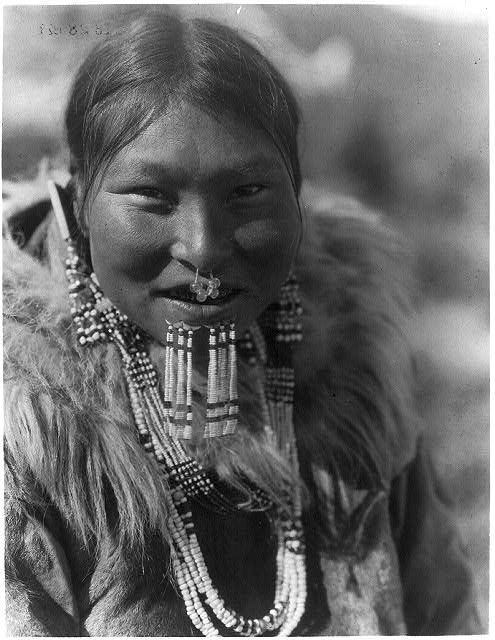

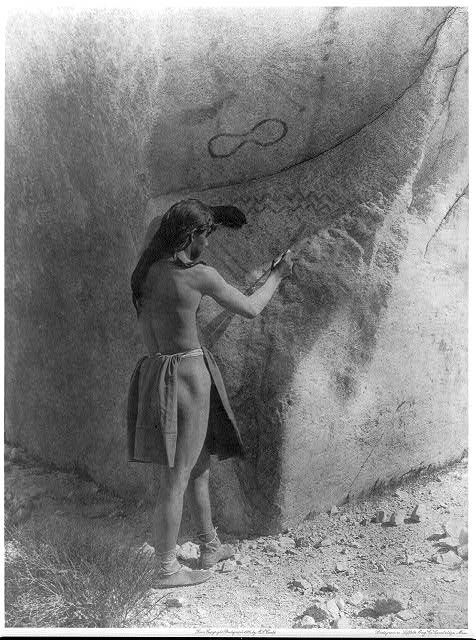

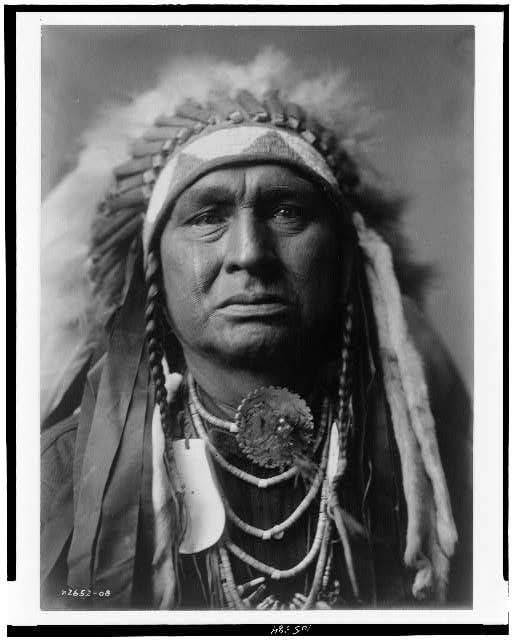

Ask the typical Euro-American to conjure up an image of a Native American and there's a chance that they might still be informed by the work of photographer Edward S. Curtis. Between 1907 and 1930, Curtis traveled North America, recording more than 40,000 images of people in more than 80 different tribes, creating thousands of wax cylinder recordings of indigenous songs and writing down stories, histories and biographies, writes Alex Q. Arbuckle for Mashable.

The documentary project ultimately became a 20-volume series, called The North American Indian, a magnum opus that The New York Herald called "the most ambitious enterprise in publishing since the production of the King James Bible," as Gilbert King reports for Smithsonian.com.

The last volume of the project was published in 1930. Today, more than 1,000 of the images he produced are available online through the Library of Congress, writes Josh Jones for Open Culture.

Jones points out that the documentary images Americans associate with the early 20th century—photographs captured by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and others—are all influenced by Curtis' work. But it's important to note that the photographer and amateur ethnologist's legacy added to the myth that Native Americans were a stoic, rapidly vanishing people, based on the way he depicted them in his photographs.

At the time, his appreciation of the people he photographed may have seemed laudable when compared to the intolerance of many of his contemporaries. However, his legacy today is of furthering false stereotypes about Native Americans as well as failing to confront the reality that he saw around his lens, of the devastating harm that United States policies were doing to indigenous people.

In a crowd-funding campaign for her own work on modern-day Native Americans living in Los Angeles, Navajo photographer and filmmaker Pamela J. Peters writes that these stereotypes that Curtis' work depicted remain fresh today. "[They] have been recreated, updated and reinforced by more recent generations, so that most Angelenos and Americans as a whole still don’t see American Indians as modern people, only as relics of the past."

King writes that at the same time as Curtis' travels, Native American children were being taken from their parents and forced into boarding schools. Curtis did not document that. He also retouched his images to remove signs of modern life — a clock, for example, became a fuzzy blur in the photograph titled In a Piegan Lodge.

"Yet, because of Curtis’ thorough documentation, some present-day tribal members utilize The North American Indian to identify ancestors and cultural objects critical to their histories," writes curator Deana Dartt of the Portland Art Museum. There is value in viewing Curtis' work with a critical eye: Dartt featured Curtis' work in a recent exhibition that juxtaposed the century-old photographs with the work of contemporary Native American photographers.

“If we are going to show the Curtis work, we had to do so in a way that really unpacks the critical issues and also privileges the contemporary Native voice over the voice of [Curtis],” Dartt tells Dalton Walker of Native Peoples. The exhibition just closed on May 9 and featured Zig Jackson, Wendy Red Star and Will Wilson. Fortunately, their portfolios can be explored online.

Portland-based Red Star is a multimedia artist whose work is informed by her cultural heritage and upbringing on the Apsáalooke reservation in south-central Montana. Her photographs pop with vivid colors as she mixes stereotypical and authentic imagery. In her self-portrait series "Four Seasons," she wears traditional garb, an image that might first seem familiar at first. "[B]ut upon further inspection, the viewer can see tacks holding up the background, many of the animals are inflatable toys, and cellophane [is] used to evoke the reflective quality of water," writes Luella N. Brien for Native Peoples. In the exhibition, she altered familiar images of Medicine Crow and other famous Native American leaders with notes and extra information, sometimes drawing a connection to herself.

"Through all this artwork, Red Star makes a powerful move to reclaim her own history," writes Marissa Katz for Go Local PDX.

Zig Jackson, also known as Rising Buffalo, is of Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara descent. He was the first Native American photographer whose work was collected by the Library of Congress. He strives to dismantle stereotypes, document the commodification of Native American culture and questions the role of photography itself. His two series "Indian Photographing Tourist Photographing Indian," and "Indian Photographing Tourist Photographing Sacred Sites" are especially effective.

"I am impatient with the way that American culture remains enamored of one particular moment in a photographic exchange between Euro-American and Aboriginal American societies: the decades from 1907 to 1930 when photographer Edward S. Curtis produced his magisterial opus," writes Wilson, a Diné photographer who grew up in the Navajo Nation on his website. In his work, The Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange, he writes that he seeks to supplant the portraits Curtis took with his own documentary mission. His series features "tintypes" that help his work mess with time. He also collaborates with his sitters to produce his portraits, rather than directing them to come off any certain way.

Stereotypes about Native Americans persist, but these artists and many others are making a powerful statement about Native people today, who are working against the image embedded by Curtis in the popular consciousness 100 years ago.