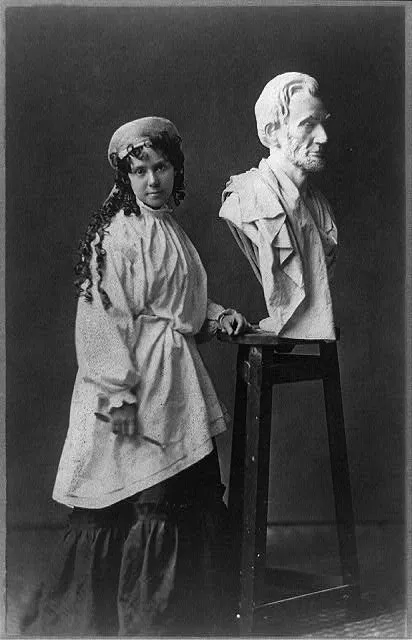

This Ambitious Young Sculptor Gave Us A Lincoln For the Capitol

Vinnie Ream was the first female artist commissioned to create a work of art for the U.S. government

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/1c/b81cd890-badf-4880-8db9-ae66b4da547b/ream2.jpg)

Lincoln stands in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, staring contemplatively down at the marble Emancipation Proclamation in his right hand. He’s wearing the outfit he word the night he was assassinated: “a bow tie, a single-breasted vest and… double-breasted frock coat,” according to the Architect of the Capitol. On the statue’s base are inscribed two names: Abraham Lincoln and Vinnie Ream.

Ream, born on this day in 1847, was only 18 when she started work on the memorial, and she had both known and sculpted Lincoln during his life. She stands out as an unconventional and talented figure in the Washington of the 1860s and 1870s, and her artistic relationship with Lincoln allowed her to capture him in a unique light.

Ream’s career was a major diversion from the kinds of things expected of middle-class women of the time, writes art historian Melissa Dabakis. She was 14 when the Civil War began, living in D.C. after being raised on the Wisconsin frontier. The war created new opportunities for women to work, and Ream worked at the post office and as a clerk for Missouri Congressman James Rollins before apprenticing with Washington sculptor Clark Mills when she was 17, in 1864.

Rollins was the one who introduced her to Mills, writes Stacy Conradt for Mental Floss: she was already known as a talented painter. She also proved to be a talented sculptor, and her connections to Congress continued to prove useful in her career. “After creating small, medallion-sized likenesses of General Custer and many Congressmen, including Thaddeus Stevens, several senators commissioned Ream to make a marble bust–and this was just over a year after she had picked up the skill,” writes Conradt. She was allowed to pick who she wanted to sculpt–with characteristic boldness, she picked Lincoln.

The president initially had no interest in sitting for a sculpture, something that would take months. However, he relented when he heard “that she was a struggling artist with a Midwestern background not dissimilar to his own,” Conradt writes. She spent half an hour per day with him for five months to sculpt the bust.

Ream was a talented if inexperienced sculptor, as her portrayals of Lincoln demonstrated. But she was also a smart and ambitious businesswoman. In the aftermath of Lincoln's assassination, when lawmakers were searching for a sculptor to memorialize him in a piece that would stand in the Capitol, she actively campaigned for the commission, winning out against 18 other more experienced sculptors, including her mentor Mills.

“It would take four and a half years before the work would be completed,” writes historian Gregory Tomso, “and during this time Ream became the center of one of the most public and divisive debates ever to take place in America concerning the relationship between art and American nationhood.”

Ream’s statue of Lincoln was contemplative, emotional and realistic–a big departure from American sculpture that portrayed leaders as larger-than-life and idealized figureheads, Tomso writes. Its realism stood in contrast to the classical forms of sculpture favored by those who saw Washington as an “American Athens,” he writes–take, for example, the 1920 Lincoln Memorial. And because of who Ream was, the sculpture was particularly controversial–she was a woman under 20, from a family that was not wealthy, who courted friendships with senators.

“Bursting in on the professional art world in a daring manner, Ream also actively marketed herself and her sculpture by staging events in her studio and courting newspaper attention,” Dabakis writes. Like other nineteenth-century artists, she used her novelty to get access to opportunity–leaving America with the lasting legacy of a sculpture created by someone who had spent a significant amount of time with Lincoln near the end of his life but who had lived to see him pass into public memory.

“So lately had I seen and known President Lincoln, that I was still under the spell of his kind eyes and genial presence when the terrible blow of his assassination came and shook the civilized world,” she wrote later. “The terror, the horror, that fell upon the whole community has never been equaled.”