This African American Artist’s Cartoons Helped Win World War II

Charles Alston knew how to turn art into motivation

Rosie the Riveter. A pointing Uncle Sam. Art has always been a powerful motivator—which is why it can be such an effective medium for political messaging. But though Rosie and Sam have gained iconic status since the two world wars, fewer people remember the compelling war effort campaigns that specifically targeted African Americans.

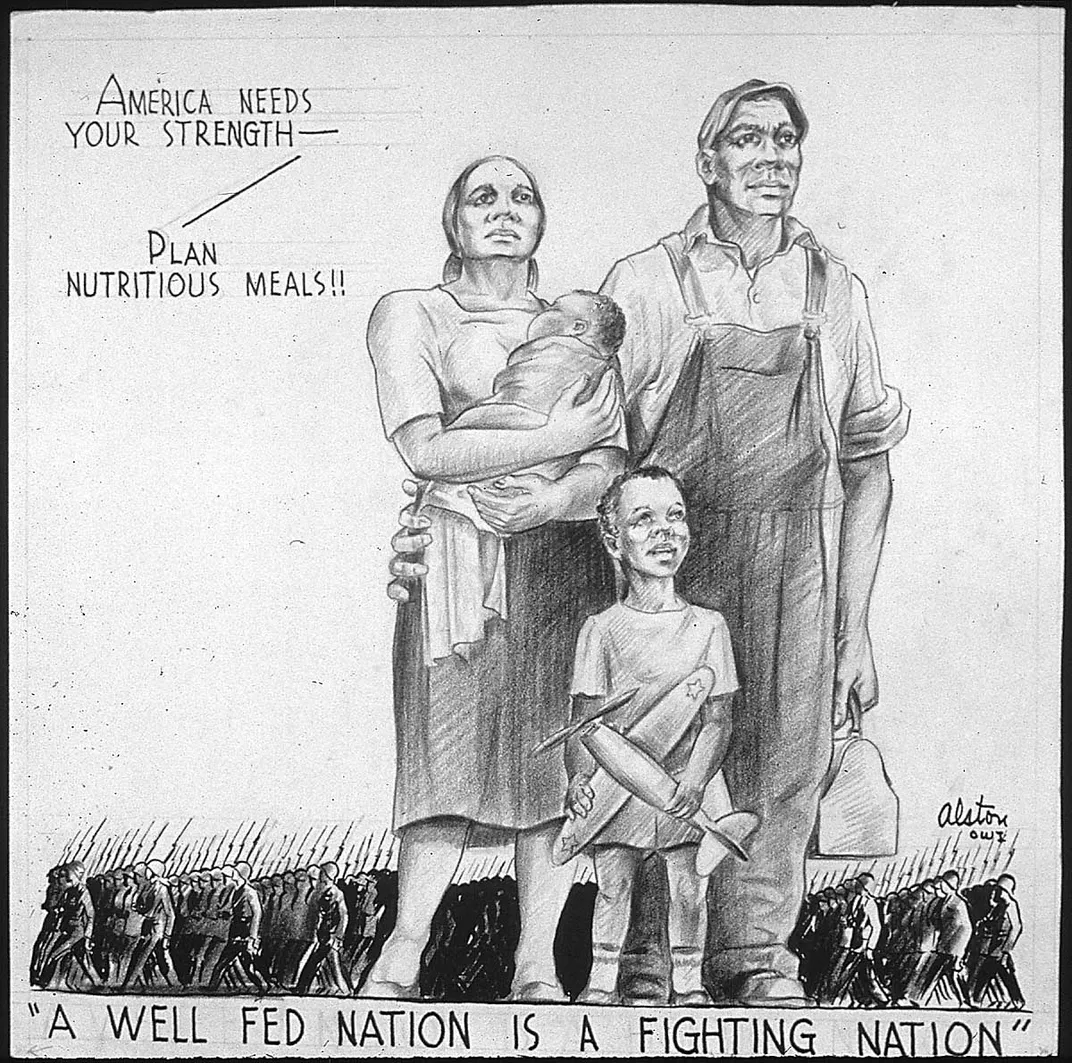

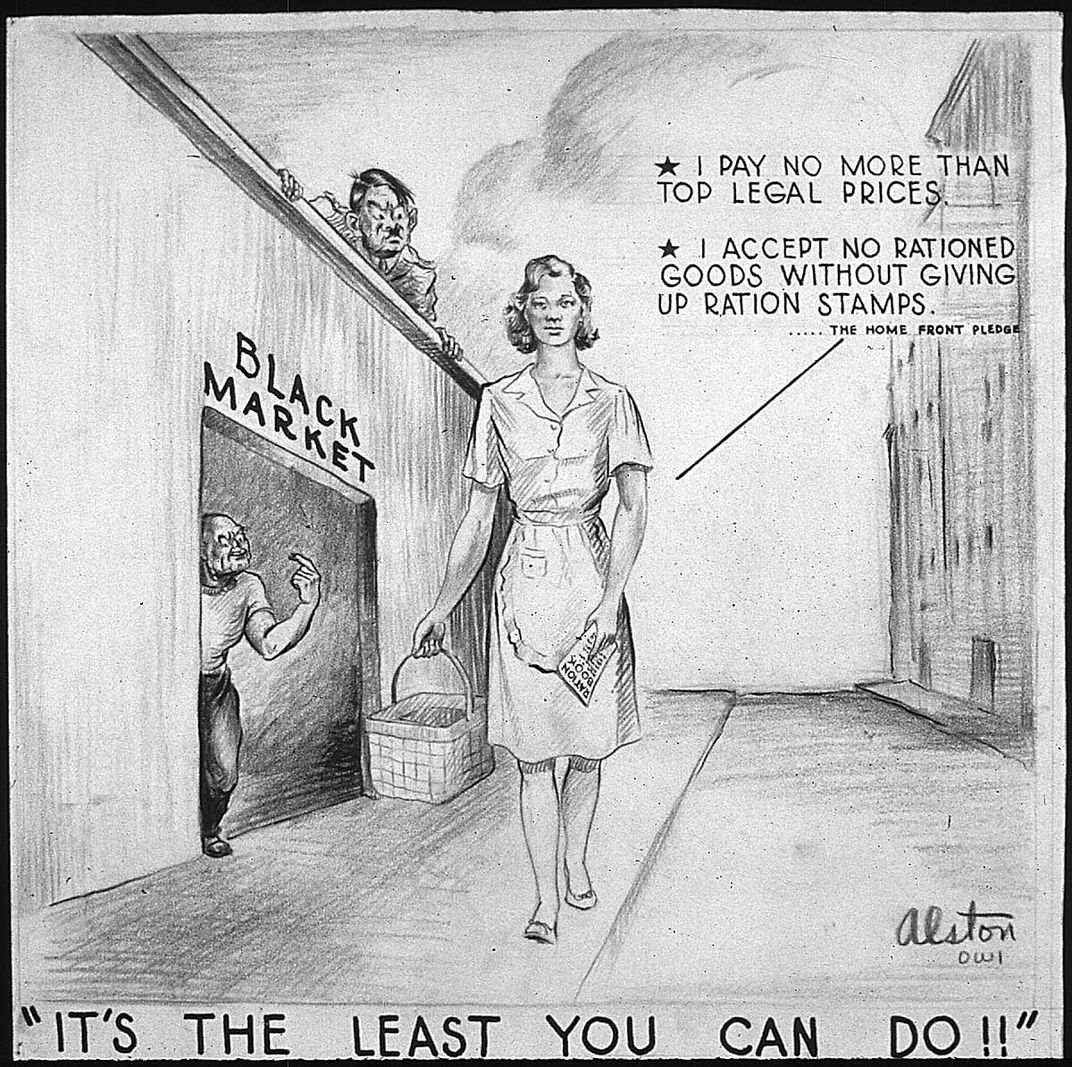

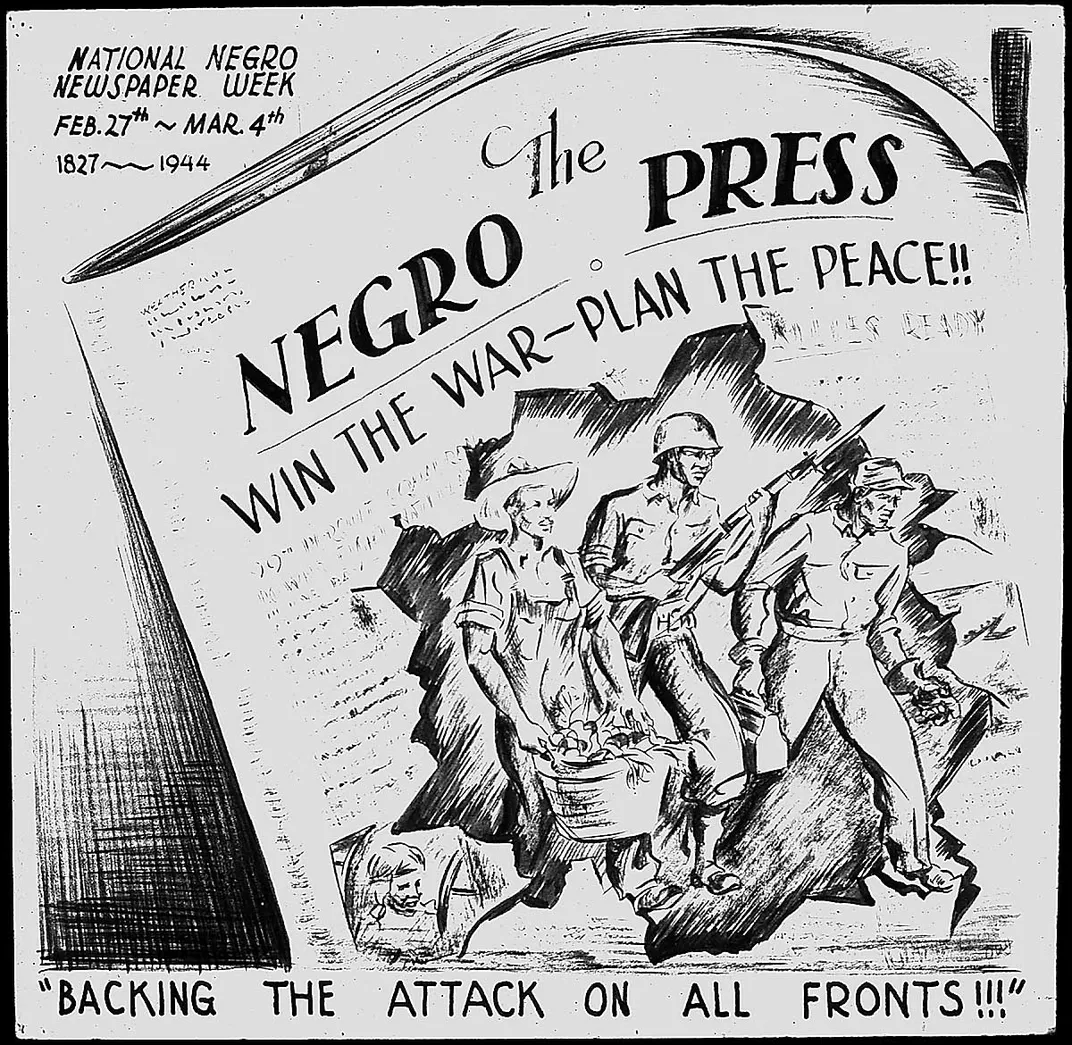

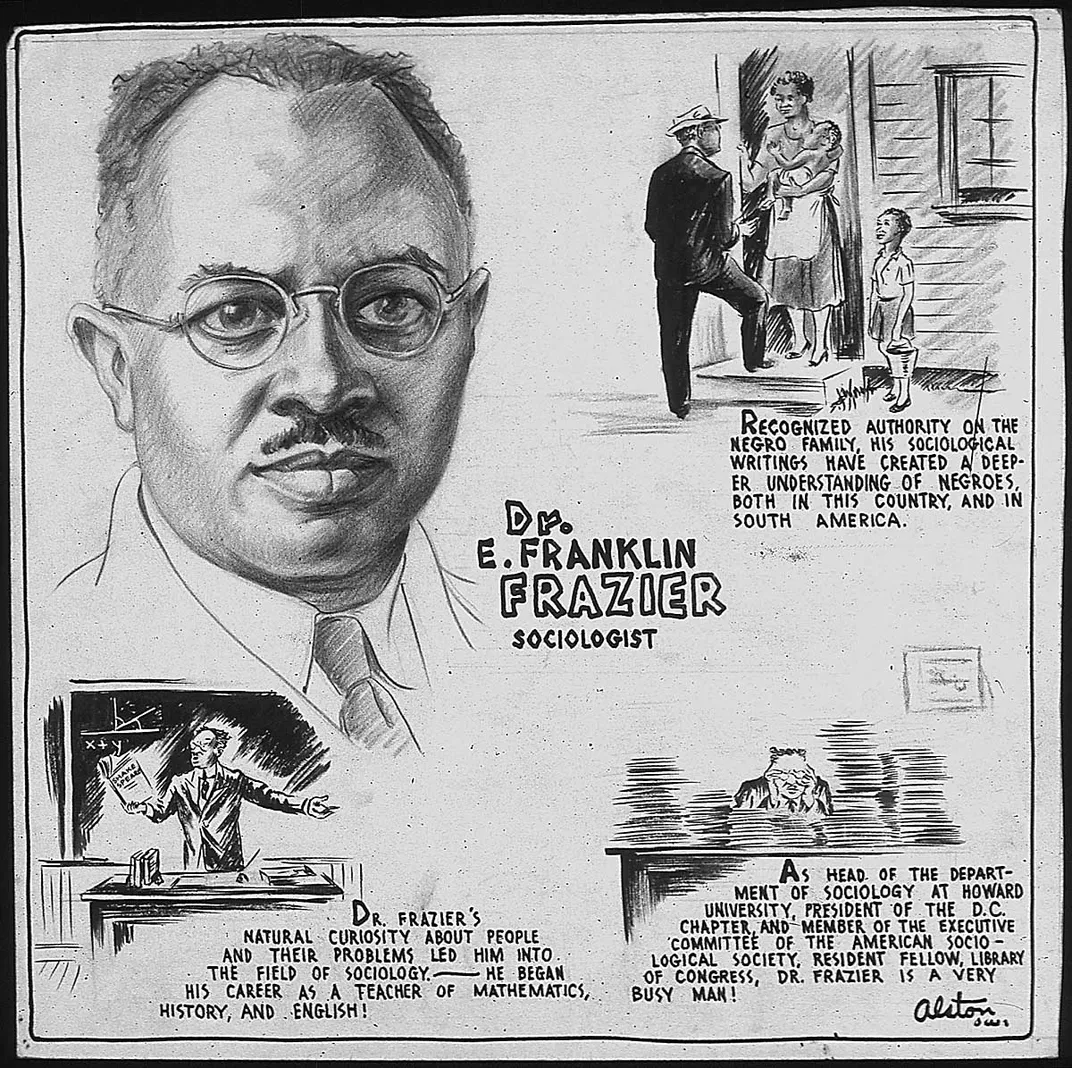

As Jessie Kratz writes for the National Archives blog, the Office of War Information hired a black artist named Charles Alston to create a series of motivational drawings especially for African American newspapers during World War II. His subject matter ranged from famous black heroes to the necessity of growing victory gardens—all in an attempt to boost morale and African American war contributions.

The drawings were designed for and distributed through black newspapers, the press that offered powerful news for and about black life during an era of segregation. The black press was also ambivalent about the United States’ entry into World War II—a stance that reflected the view of many African Americans that it was impossible to fight for freedom abroad when black lives were not valued at home. One black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, was even investigated for treason and sedition because of its “Double V” campaign, which declared that black people should fight for a dual victory over enemies at home and abroad. Today, the campaign is seen as a precursor to the Civil Rights Movement.

Alston’s images battled that ambivalence by highlighting the accomplishments of African Americans within the U.S. Armed Forces and their necessity to the war effort at home, and spotlighted famous black people like Willa Brown, the United States’ first African American woman pilot, in biographical cartoons.

Despite a segregated military, black people contributed significantly to the war effort, serving bravely overseas in the military, volunteering for war duty and working in munitions factories and participating in homefront privations. Perhaps some were inspired to serve because of Alston’s images.

Alston didn’t only draw cartoons. In the 1930s, he produced a series of murals about black history for the Harlem Hospital Center under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration, and his long career included stints as a painter and art teacher. But you may know him best as the sculptor of the bust of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. that currently sits in the Oval Office. Another copy is owned by the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture—a tribute to an artist who knew how to turn art into motivation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/29/cf294593-cff4-4dea-bf62-1cde8beabff1/03-0046a.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)