Egypt’s Mammal Extinctions Tracked Through 6,000 Years of Art

Tomb goods and historical texts show how a drying climate and an expanding human population took their toll on the region’s wildlife

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/0d/9e0d5080-300b-497e-b30c-fb1f72f80f1c/42-19305416.jpg)

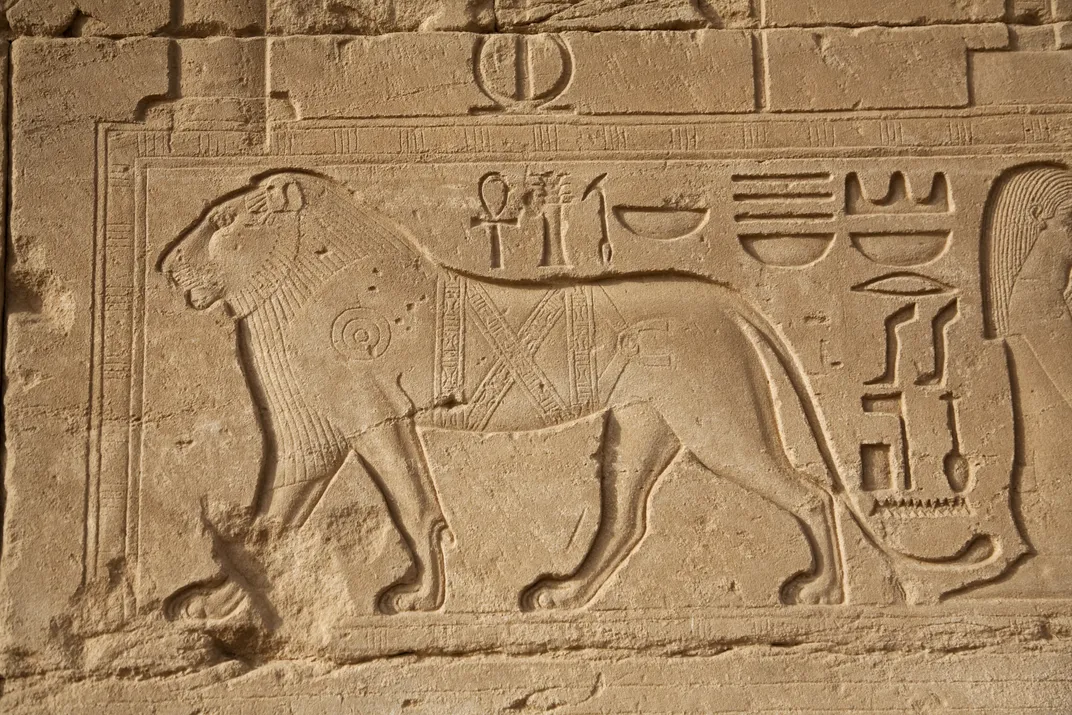

Ancient Egypt’s highly decorated tombs and funerary objects—meant to ensure a safe trip into the afterlife—also hold a rich record of the region’s wildlife. Now scientists have used that art, along with other paleontological, archaeological and historical evidence, to map out the rise and fall of Egypt’s large mammals and match those patterns to changes in climate and human interactions.

The results, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offer an unprecedented glimpse into the ways population growth and climate change can influence an ecosystem over millennia—perhaps giving scientists crucial insight into the long-term impacts of modern human activities.

Justin Yeakel at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and his colleagues began with a book, The Mammals of Ancient Egypt, which documented the distribution of animal communities from their artistic representations and historical records. According to the book, for example, two species of rhinoceroses had once been present but had disappeared by the Late Predynastic or Early Dynastic periods, approximately 5,000 years ago. The researchers then combined this information with other animal records, such as ancient writings. Lions, for instance, were present during the time of Herodotus, around 2,400 years ago, but had become rare a little over a century later, according to Aristotle.

To analyze the patterns of extinctions, the scientists created a computer model that let them relate the disappearances to predator-prey dynamics and changes in local climate. Previous geological and paleontological research shows that the Egypt of 6,000 years ago was very different from the landscape today. That’s because Earth is tilted on its axis with respect to the sun, and the planet wobbles slowly as it orbits, creating slight variations in its tilt that can affect global climate.

Millennia ago, northern Africa was much wetter and cooler. Monsoons struck periodically, and the Sahara was covered with lakes and vegetation. This greener version of Egypt was home to a mix of wildlife more like the one now found in East Africa, with 37 species of large mammals including lions, wildebeest, warthogs and spotted hyenas.

The region began to dry out about 5,000 years ago, a time that coincides with the fall of the Uruk Kingdom in Mesopotamia (located in present-day Iraq) and the rise of the pharaohs in Egypt. The Egyptian people at this time switched from a mobile, pastoral life to one of agriculture and subsistence hunting. The new research shows that several species of antelope, along with giraffes and rhinoceroses, disappeared around the same time—extinctions that could be due to overhunting of herbivores. Shortly afterward, the long-maned lion vanished.

Egypt became even drier around 4,200 years ago, during a time known as the “First Intermediate Period” or the “dark period.” The region depended on yearly flooding of the Nile to inundate the land and leave behind nutrient-laden silt to feed agricultural fields. But during the dark period, this flooding became inconsistent, crop yields dropped and famine ensued. War and chaos reigned, and eventually the Old Kingdom—and with it, the “Age of the Pyramids”—ended. This is when the roan antelope and African wild dog disappeared from the records.

A third aridification event occurred about 3,000 years ago, again bringing drought and an end to the New Kingdom, a time that included Tutankhamun and 12 kings named Ramses. Egypt’s short-maned lions, revered as sacred and even occasionally mummified, vanished around this time.

Then about 150 years ago, as Egypt’s growing population became more industrialized, more species disappeared, including leopards and wild boar. Today, only 8 of the original 37 large-bodied mammals remain.

Egypt’s complex food web didn’t suffer too badly from the first few species disappearances, according to the study. When some herbivores were lost, most predators still had plenty of other prey animals to keep them fed. But as more species were removed, the ecosystem became increasingly unstable, and eventually most animals just couldn’t survive in a dry landscape populated with an ever-growing human population.

While the team notes that they can’t assign a specific cause to any particular extinction event, the model does show that the pattern of extinctions did not occur randomly, perhaps helping to refine theories about modern drops in biodiversity. “The trajectory of extinctions over 6,000 [years] of Egyptian history is a window into the influence that both climatic and anthropogenic impacts have on animal communities,” the researchers write.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/f3/dff376ae-bc0e-4f56-ad2b-731f036fa6af/42-19305445.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)