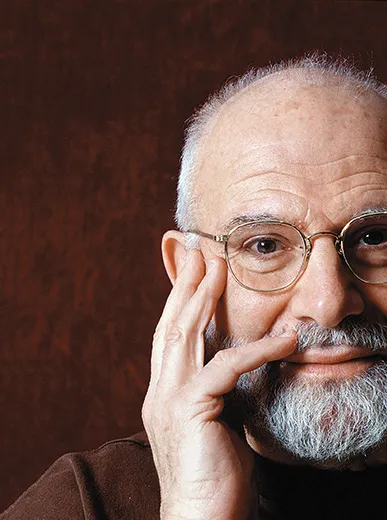

Why Oliver Sacks is One of the Great Modern Adventurers

The neurologist’s latest investigations of the mind explore the mystery of hallucinations – including his own

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Gonzo-Neurologist-631.jpg)

It’s easy to get the wrong impression about Dr. Oliver Sacks. It certainly is if all you do is look at the author photos on the succession of brainy best-selling neurology books he’s written since Awakenings and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat made him famous. Cumulatively, they give the impression of a warm, fuzzy, virtually cherubic fellow at home in comfy-couched consultation rooms. A kind of fusion of Freud and Yoda. And indeed that’s how he looked when I spoke with him recently, in his comfy-couched consultation room.

But Oliver Sacks is one of the great modern adventurers, a daring explorer of a different sort of unmapped territory than braved by Columbus or Lewis and Clark. He has gone to the limits of the physical globe, almost losing his life as darkness fell on a frozen Arctic mountainside. He’s sailed fragile craft to the remotest Pacific isles and trekked through the jungles of Oaxaca. He even lived through San Francisco in the 1960s.

But to me, the most fearless and adventuresome aspect of his long life (he’s nearing 80) has been his courageous expeditions into the darkest interiors of the human skull—his willingness to risk losing his mind to find out more about what goes on inside ours.

I have a feeling this word has not yet been applied to him, but Oliver Sacks is a genuine badass, and a reading of his new book, Hallucinations, cements that impression. He wades in and contends with the weightiest questions about the brain, its functions and its extremely scary anomalies. He is, in his search for what can be learned about the “normal” by taking it to the extreme, turning the volume up to 11, as much Dr. Hunter Thompson as Dr. Sigmund Freud: a gonzo neurologist.

You get a sense of this Dr. Sacks when you look around the anteroom to his office and see a photo of the young doctor lifting a 600-pound barbell at a weight-lifting competition. Six hundred pounds! It’s more consonant with the Other Side of Dr. Sacks, the motorcyclist who self-administered serious doses of psychedelic drugs to investigate the mind.

And though his public demeanor reflects a very proper British neurologist, he’s not afraid to venture into some wild uncharted territory.

At some point early in our conversation in his genteel Greenwich Village office I asked Sacks about the weight-lifting picture. “I wasn’t a 98-pound weakling,” he says of his youth in London, where both his parents were doctors. “But I was a soft fatty...and I joined a club, a Jewish sports club in London called the Maccabi, and I was very affected. I remember going in and seeing a barbell loaded up with some improbable amount, and I didn’t see anyone around who looked capable of touching it. And then a little grizzled old man came in who I thought was the janitor, stationed himself in front of it and did a flawless snatch, squat-snatch, which requires exquisite balance. This was my friend Benny who’d been in the Olympic Games twice. I was really inspired by him.”

It takes a strong man of another kind for the other kind of heavy lifting he does. Mental lifting, moral uplifting. Bearing on his shoulders, metaphorically, the heavyweight dilemmas of a neurologist confronted by extraordinary dysfunctional, disorderly, paradoxical brain syndromes, including his own. In part, he says, that’s why he wrote this new book, this “anthology,” as he calls it, of strange internal and external hallucinations: as a way of comforting those who might only think of them as lonely, scary afflictions. “In general people are afraid to acknowledge hallucinations,” he told me, “because they immediately see them as a sign of something awful happening to the brain, whereas in most cases they’re not. And so I think my book is partly to describe the rich phenomenology and it’s partly to defuse the subject a bit.”

He describes the book as a kind of natural scientist’s typology of hallucinations, including “Charles Bonnet syndrome,” where people with deteriorating vision experience complex visual hallucinations (in one case, this involved “observing” multitudes of people in Eastern dress); blind people who don’t know—deny—they’re blind; hallucinations of voices, of the presence of God; tactile hallucinations (every one of the five senses is vulnerable); his own migraine hallucinations; and, of course, hallucinations engendered by hallucinogens.

What makes this book so Sacksian is that it is pervaded with a sense of paradox—hallucinations as afflictions and as perverse gifts of a sort, magic shows of the mind. This should not be surprising since as a young neurologist, Sacks became famous for a life-changing paradoxical experience that would have staggered an ordinary man.

In case you don’t recall the astonishing events that made Sacks the subject of the Oscar-winning film Awakenings, they began when he found himself treating chronic psychiatric patients in a dusty and neglected hospital in the Bronx (Robin Williams played him in the film; Robert De Niro played one of his patients). Dozens of his patients had been living in suspended animation for decades as the result of the strange and devastating aftereffects of the encephalitis lethargica (“sleeping sickness”) epidemic that raged through the ’20s, which had frozen them in time, semiconscious, mostly paralyzed and virtually unable to respond to the outside world.

It was grimly horrifying. But Sacks had an idea, based on his reading of an obscure neurophysiology paper. He injected his patients with doses of L-dopa (which converts into dopamine, a primary neurotransmitter), and a veritable miracle ensued: They began to come alive, to awaken into life utterly unaware in most cases that decades had passed, now suddenly hungry for the life they’d lost. He’d resurrected the dead! Many moments of joy and wonder followed.

And then disturbing things began to happen. The dopamine’s effectiveness seemed to wear off in some cases. New troubling, unpredictable symptoms afflicted those who didn’t go back to “sleep.” And the patients experienced the doubly tragic loss of what they had all too briefly regained. What a doctor’s dilemma! What a tremendous burden Sacks bore in making decisions about whether he was helping or perhaps further damaging these poor souls whose brains he virtually held in his hands. How could he have known some of the miraculous awakenings would turn into nightmares?

I must admit that I’ve always felt a little fearful just contemplating Sacks’ books. The panoply of things that can go frighteningly wrong with the brain makes you feel you are just one dodgy neuron away from appearing in Sacks’ next book.

I felt a certain kind of comfort, however, in talking to him in his consultation room. I wasn’t seeing things, but who knows, should anything go wrong, this was the place to be. There was something soothingly therapeutic about the surroundings—and his presence. I didn’t want to leave for the hallucinated reality of the outside world.

The book Hallucinations in particular gives one a sense of the fragile tenuousness of consensus reality, and the sense that some mysterious stranger hidden within the recesses of your cortex might take over the task of assembling “reality” for you in a way not remotely recognizable. Who is that stranger? Or are you the stranger in disguise?

It sounds mystical but Sacks claims he has turned against mysticism for the wonder of the ordinary: “A friend of mine, a philosopher, said, ‘Well, why do all you neurologists and neuroscientists go mystical in your old age?’ I said I thought I was going in the opposite direction. I mean I find mystery enough and wonder enough in the natural world and the so-called ‘order experience,’ which seems to me to be quite extra ordinary.”

“Consensus reality is this amazing achievement, isn’t it?” I ask Sacks. “I mean that we share the same perceptions of the world.”

“Absolutely,” he replies. “We think we may be given the scene in front of you, the sort of color, movement, detail and meaning, but it’s an enormous—a hell of a—marvel of analysis and synthesis [to recreate the world accurately within our mind], which can break down at any point.”

“So how do we know consensus reality bears any relationship to reality-reality?” I ask him.

“I’m less moved by that philosophical question of whether anything exists than by something more concrete.”

“OK, good,” I say, “What about free will?”

“You call that more concrete?” he laughs with a bit of mock indignation.

Nonetheless, free will is still a hot topic of debate between philosophers and a large school of neuroscientists who believe it doesn’t exist, that every choice we make is predetermined by the neurophysiology of the brain.

“I think that consciousness is real and efficacious and not an epiphenomenon [a minor collateral effect],” he says, “and it gives us a way of unifying experience and understanding it and comparing with the past and planning for the future, which is not possessed by an animal with less consciousness. And I think one aspect of consciousness is the illusion of free will.”

The “illusion of free will.” Whoa! That was a slap in the face. How can one tell, especially one who has written a book about hallucinations, whether free will is an illusion—a hallucination of choice, in effect produced by various material deterministic forces in the brain that actually give you no real “choice”—or a reality?

He doesn’t put it that way and in fact comes up with what I think is an important insight, the kind of wisdom I was seeking with these abstract questions: “I think,” he says, “we must act as if we had free will.” In other words it’s a moral imperative to take responsibility for our choices—to err on the side of believing we can freely choose, and not say “my neurons made me do it” when we go wrong.

At last I found a subject both concrete enough for Sacks and very much on his mind in a troubling way. One of the most controversial issues in the neuropsychiatric community—and in the community of tens of millions of Americans who take mood disorder pills—is the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is now being revised. Through its coded diagnosis system based on supposedly objective, quantifiable “criteria” for mental illness, the DSM is the primary tool in reshaping the way we think about what is “normal” and what is “malfunctioning.” This is because the health insurance industry demands a certifiable DSM diagnosis from a psychiatrist before it will agree to subsidize payment for medication and treatment. So to get their patients any affordable help, doctors must fit each case into the diagnostic code.

Sacks has big problems with the DSM and the culture of simplistic diagnosis it’s given birth to. He argues that this has been an unfortunate development leading to often-crude, falsely “objective” definitions of patients’ maladies that effectively treat the delicate processes of the mind with a sledgehammer rather than a scalpel, obliterating questions such as what is the difference between “justified” sadness and clinical depression—should we be allowed to feel bad in any way or must we maintain a state of “normality,” even when it is mind-numbing?

“I gave a talk recently on ‘the case history,’” Sacks says. “I have seen clinical notes in psychiatry charts crash in the last 30 years, since the first DSM.”

“‘Clinical notes crashing?’”

Here he becomes eloquent; the matter is clearly close to his heart.

“Meaning wishing one would have beautiful, thoughtful, sensitive, often handwritten descriptions of what people are doing through their lives, of significant things in their lives. And now if you use them without rushing to a diagnosis or [DSM] coding for which one would be paid—in the psychiatric charts you’re liable to see a list of criteria and then say these meet the criteria for schizophrenia, manic depressive Axis III or whatever...”

He laments turning the patient’s mind into a commodity for the pharmacology and health insurance industries. “One may need clarification and consensus ... but not at the expense of what [anthropologist] Clifford Geertz used to call ‘thick description’”—the kind of description that doesn’t lump patients together but looks carefully at their individuality. “And I’m worried about it and my mentor Dr. A.R. Luria worried about it. He would say that the art of observation, description, the comments of the great neurologists and psychiatrists of the 19th century, is almost gone now. And we’re saying it must be revived. I try to revive it after a fashion and so, too, are an increasing number of others who feel that in some ways the DSM has gone too far.”

This is personal for him in two ways.

As a writer and as a scientist, Sacks justly places himself in the tradition of natural scientists like “the great neurologists of the 19th century,” putting “thick description” ahead of rigid prefab diagnosis. It’s a tradition that looks at mental phenomena as uniquely individual, rather than collapsible into classes and codes.

And then, most personal of all, there was the case of his own brother.

“You know, I sort of saw this at home,” he tells me. “I had a schizophrenic brother and he spent the later 50 years of his life heavily medicated and I think partially zombified by this.”

Wishfully, almost wistfully, he tells me about “a little town in Belgium called Geel,” which is “extraordinary because every family has adopted a mad person. Since the 13th century, since 1280,” he says. “I’ve got a little thing I wrote about it, I visited there.”

I’m fairly sure this solution isn’t scalable, as they say, but clearly he believes it’s much more humane than “zombification.” And what an amazing model of communal, loving attentiveness to stricken souls.

The rarity of this altruism prompted me to ask Sacks whether he thought human nature was the best of all possible states or morally depraved.

“E.O. Wilson put this nicely,” Sacks says, “in his latest book when he feels that Darwinian selection has produced both the best and the worst of all possible natures in us.” In other words, the savage struggles of survival of the fittest, and at the same time, the evolutionary advantage conferred by cooperation and altruism that has become a recent subject of evolutionary psychology.

Yes, Sacks says, and our better natures “are constantly threatened by the bad things.”

“A world full of murder and genocide—is it our moral failing or a physio-chemical maladjustment?”

“Well, prior to either of those,” he says, “I would say it is population. There are too many people on this planet and some of the difficulties which Malthus [the economist who warned that overpopulation could lead to doom] wondered about in 1790—pertain, although it doesn’t seem to be so much about the limits of food supply as the limits of space and the amount of soiling, which includes radioactive waste and plastic, which we are producing. Plus religious fanaticism.”

The mysteries of religious experience—not just fanaticism but ecstaticism, you might say—play an important part in the new hallucinations book. Yes, there are some astonishing magic shows. Sacks writes of an afternoon back in the ’60s when a couple he knew showed up at his house, had tea and a conversation with him, and then departed. The only thing is: They were never there. It was a totally convincing hallucination.

But it’s a different kind of “presence hallucination” he writes about that I found even more fascinating. The religious presence hallucination. It is often experienced by epilepsy sufferers before or during seizures—the impression of sudden access to cosmic, mystical, spiritual awareness of infinitude. Where does it come from? How does the mind invent something seemingly beyond the mind?

Sacks is skeptical of anything beyond the material.

“A bus conductor in London was punching tickets and suddenly felt he was in heaven and told all the passengers, who were happy for him. He was in a state of religious elation and became a passionate believer until another set of seizures ‘cleared his mind’ and he lost his belief.” And there’s a dark side to some of these “presence hallucinations” that are not always so tidily disposed of as with the bus driver.

“I think I mention this in the epilepsy chapter in the book—how one man had a so-called ecstatic seizure in which he heard Christ telling him to murder his wife and then kill himself. Not the best sort of epiphany. He did murder his wife and was stopped from stabbing himself.

“We don’t know very much about the neurophysiology of Belief,” he concedes.

The closest he came to a religious hallucination himself, he says, was “a sense of joy or illumination or insight when I saw the periodic table for the first time. Whereas I can’t imagine myself having an experience of being in the presence of God, although I occasionally tried to in my drug days, 45 years ago, and said, ‘OK God, I’m waiting.’ Nothing ever happened.”

When I ask him if he was a materialist—someone who believes all mental phenomena including consciousness and spiritual experiences can be explained by physics and biology—rather than a “dualist”—one who believes consciousness, or spirituality, is not tied to neurochemistry—he replies, “I would have to say materialist. I cannot conceive of anything which is not embodied and therefore I cannot think of self or consciousness or whatever as being implanted in an organism and sort of released at death.”

I wonder if this skepticism extended to love. Just chemistry?

“I think that being in love is a remarkable physiological state, which, for better or worse, doesn’t last forever. But,” he adds, and this is the remarkable part, “Vernon Mountcastle [a neurological colleague] wrote me a letter when he was 70; he said he was retiring from laboratory work and would be doing scholarly work—he’s still doing that in his 90s now—but he said in this letter that ‘Any piece of original research, however trivial, produces an ecstasy like that of first love, again and again.’

“I love that description of love in science,” Sacks says.

I love that description of love in life. “First love again and again?” I repeat.

“Yes,” Sacks says.

“Because we used to think that nothing could repeat first love?” I ask.

“Yeah.”

“And yet a rush of insight...?”

“Yeah,” says Sacks dreamily, sounding like a man who has experienced this ecstasy of first love again and again.

“Weisskopf, the physicist, wrote a book called The Joy of Insight,” he says, “which is very much along those lines. He was also a very good amateur musician and he had one chapter called ‘Mozart Quantum Mechanics,’ in which he tried to compare the joy of one with the joy of the other.”

“The joy of insight—does love have something to do with the joy of mutual insight? Two people having a special depth of insight into the other?”

“Well, one certainly can love when one feels this, when one is reaching to understand that depth which is very special,” he says.

Toward the end of our talk I ask Sacks what, after all his years investigating the mysteries of the mind, he still most wanted to know.

“More about how consciousness works and its basis, how it evolved phylogenetically and how it evolves in the individual.”

In part his answer has to do with the mystery of the “director” of consciousness, the self that integrates all the elements of perceptions and reflection into an “order-experience” of the world. How does this “director”—this “self”—evolve to take charge or “self-organize” in the brain, as some neuroscientists put it. And how does he or she lose control in hallucinations?

Another question of consciousness he wants to know more about is the mystery of consciousness in animals. “As a scuba diver I’ve seen plenty of cuttlefish and octopus. Darwin talks about this very beautifully in The Voyage of the Beagle. He sees an octopus in a tidal pool and he feels it watching him just as closely as he is watching it. And one can’t avoid that sort of impression.”

You’ve got to love Dr. Sacks’ insatiable curiosity, the sense that he is ready to fall in love again and again and that the insights never stop. What must being inside his brain be like? As I was leaving his office we had a final exchange that may provide a clue. We were talking about his own experience of hallucinations and hallucinogens and how he deplored the way the unscientific publicity show put on by the original LSD experimenters Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (later named Ram Dass), and others, set back, indeed, made “serious research on these things impossible, and it’s only resumed really in the last decade,” he says. “LSD can mess with some of the highest orders, the highest sort of processes in the brain, and it’s important to have investigation which is ethical, lawful and deep and interesting.”

He goes on to talk about why he ended his own experiments with hallucinogens.

“The last one was in February of ’67,” he recalls. “But I felt somehow tilted into the mode of wonder and creativity, which I’d known when I was much younger. While there have been dead periods, that [mode of wonder] has been with me ever since.

“So I don’t feel any psychological, let alone metaphysical, need for anything beyond daily experience and clinical experience.”

The “mode of wonder”! The wonder of the ordinary. “Once you’ve been there, done that, you don’t need to do it anymore?” I ask.

“Well, ‘there’ becomes available.”

“There” becomes available! Yes.

That’s his secret. Dr. Oliver Sacks is “there.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)