Why Do We Hiccup? And Other Scientific Mysteries—Seen Through the Eyes of Artists

In a new book, 75 artists illustrate questions scientists haven’t fully answered yet

![]()

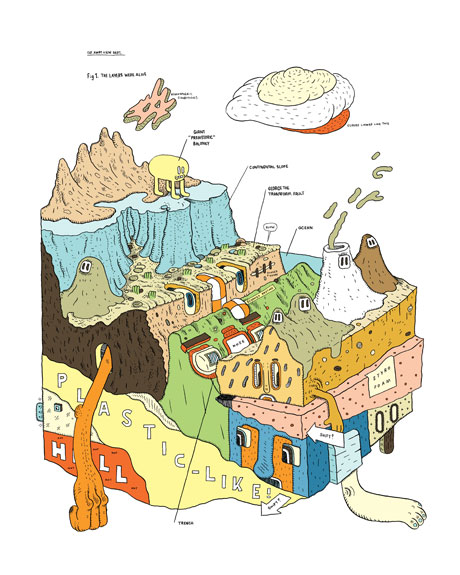

What drives plate tectonics? Illustrated by Marc Bell.

“Today we’re spoiled with an abundance of information,” write Jenny Volvovski, Julia Rothman and Matt Lamothe, in their latest book, The Where, The Why, and The How. “We carry devices that fit in our pockets but contain the entirety of human knowledge. If you want to know anything, just Google it.”

Why, for instance, are eggs oval-shaped? The authors wondered—and, in a matter of seconds, there was the answer, served up in the form of a Wikipedia entry. Eggs are oblong, as opposed to spherical, so that they roll in a contained circle (less chance for wandering eggs). They also fit into a nest better this way.

But Volvovski, Rothman and Lamothe, all partners in the design firm ALSO, see this quick answer-finding as a negative at times. In the case of the egg, they say, ”The most fun, the period of wonder and funny guesses, was lost as soon as the 3G network kicked in.”

The Where, The Why, and The How is the authors’ attempt to revel in those “mysteries that can’t be entirely explained in a few mouse clicks.” Volvovski and her coauthors selected 75 not quite answerable questions—from “Where did life come from?” to “Why do cats purr?” to “How does gravity work?”—and let artists and scientists loose on them. The artists created whimsical illustrations, and the scientists responded with thoughtful essays. ”With this book, we wanted to bring back a sense of the unknown that has been lost in the age of information,” say the authors.

Cartoonist Marc Bell took on the stumper, What drives plate tectonics? His imaginative response is pictured above.

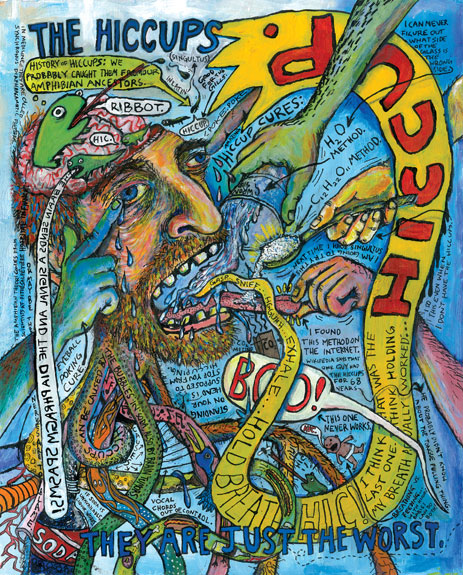

Why do we hiccup? Illustrated by Dave Zackin.

Why do we hiccup, anyway? As you can see in his busy and somewhat grotesque illustration, above, comic artist Dave Zackin is entertained by the many scientific theories and folk remedies. Scientist Jill Conte touches on these in an accompanying essay:

Hiccups happen when our diaphragm, the muscle in our chest that controls breathing, spasms involuntarily, causing a sudden rush of air into our lungs. Our vocal cords shut to stem the flow of air, thus producing the sound of a hiccup. No one knows exactly what triggers the diaphragm to spasm, although it’s probably due to stimulation of the nerves connected to the muscle or to a signal from the part of the brain that controls breathing.

Some scientists hypothesize that the neural circuitry implicated in human hiccuping is an evolutionary vestige from our amphibian ancestors who use a similar action to aid respiration with gills during their tadpole stage. Humans have maintained the neural hardware, scientists theorize, because it may benefit suckling infants who must manage the rhythm of breathing and feeding simultaneously.

Notice the tadpoles squirming out of the man’s brain? Can you find the hiccuping baby?

What defined dinosaurs’ diet? Illustrated by Meg Hunt.

And, what defined dinosaurs’ diet? In the book, Margaret Smith, a physical sciences librarian at New York University, describes how paleontologists sometimes analyze coprolites, or fossilized dinosaur feces, to determine a dinosaur’s last meal. A dino’s teeth also provide some clues, writes Smith:

Through comparing fossilized dinosaur teeth and bones to those of reptiles living today, we’ve been able to broadly categorize the diets of different kinds of dinosaurs. For example, we know that the teeth of the Tyrannosaurus rex are long, slender, and knife-like, similar to those of the komodo dragon (a carnivore), while those of the Diplodocus are more flat and stumpy, like those of the cow (an herbivore). However, whether carnivorous dinosaurs were hunters or scavengers (or even cannibals!) and whether the the herbivorous ones noshed on tree leaves, grasses, or kelp is still uncertain.

Illustrator Meg Hunt stuck to the teeth.

What is dark energy? Illustrated by Ben Finer.

A couple of years ago, Smithsonian published a story that calls dark energy the biggest mystery in the universe–I suspect that Volvovski, Rothman and Lamothe might jump on board with this mighty superlative, given the fact that they asked Michael Leyton, a research fellow at CERN, to comment on the murky topic early in the book. Leyton writes:

In 1998, astrophysicists were shocked when new data from supernovae revealed that the universe is not only expanding, but expanding at an accelerating rate…. To explain the observed acceleration, a component with strong negative pressure was added to the cosmological equation of state and called “dark energy.

A recent survey of more than 200,000 galaxies appears to confirm the existence of this mysterious energy. Although it is estimated that about 73 percent of the universe is made up of dark energy, the exact physics behind it remains unknown.

Artist Ben Finer, in turn, created a visual response to the question, What is dark energy?

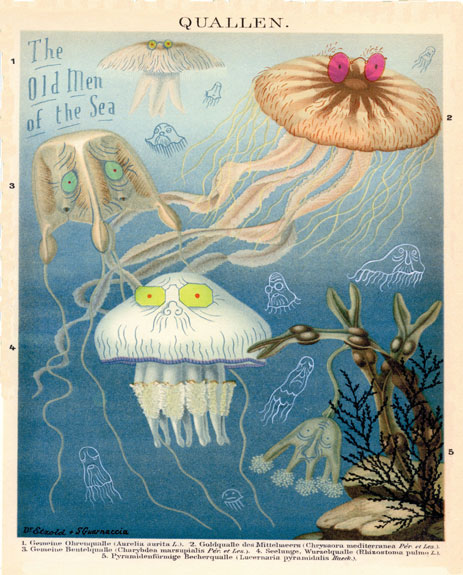

Do immortal creatures exist? Illustrated by Steven Guarnaccia.

The ALSO partners tried to assign scientific questions to artists, whose bodies of work in some way, shape or form included similar subjects or themes. Much like he recast the pigs as architects, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Frank Gehry in his book version of “The Three Little Pigs,” Steven Guarnaccia, an illustrator and former New York Times Op-Ed art director, envisioned a spinoff of Ernest Hemingway’s classic The Old Man and the Sea called The Old Men of the Sea in his response to “Do immortal creatures exist?”

So, why the wrinkly, bespectacled jellyfish? Well, engineer Julie Frey and Hunter College assistant professor Jessica Rothman’s essay inspired him:

Turritopsi nutricula, a jellyfish that lives in Caribbean waters, is able to regenerate its entire body repeatedly and revert back to an immature state after it has matured, rendering it effectively immortal. Scientists have no idea how the jellyfish completes this remarkable age reversal and why it doesn’t do this all the time. It is possible that a change in the environment triggers the switch, or it may be solely genetic.

Sometimes science is stranger than fiction.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)