What Can Old Menus From Hawaii Tell Us About Changing Ocean Health?

A study of vintage menus reveals the drastic decline of the state’s local fish populations between 1900 and 1950

To the detriment of some species, fresh fish has been a Hawaiian specialty for decades. Photo by Vincent Ma

Hawaiians knew the value of locally sourced foods decades before the term locavore became a buzzword at every Brooklyn, Portland and Northern California farmer’s market. Because of the 50th state’s isolation, Hawaii has always relied upon its easy access to bountiful local seafood to feed the islands. Seafood-heavy restaurant menus testify to this fact.

Many tourists, it turns out, view these colorful fish-filled menus as a great souvenir of their time in Hawaii. Over the years, thousands of pinched Hawaiian menus have found their way back to the mainland in suitcases and travel bags, only to wind up sitting on an attic shelf or stuffed into a drawer for the next 80-odd years. Kyle Van Houtan, an ecologist at Duke University and leader of NOAA’s Marine Turtle Assessment Program, realized the menus could serve a higher purpose than gathering dust. The stuff of breakfast, lunch and dinner plates, he realized, could potentially fill in gaps of historic records of fish populations by showing what species were around in a given year.

The cover of a 1977 menu from the Monarch Room Royal Hawaiian Hotel. Photo via The New York Public Library

The basic premise is this–if a species of fish can be readily found in large enough numbers, then it’s likely to make it on restaurant menus. Van Houtan and colleagues tracked down 376 such menus from 154 different restaurants in Hawaii, most of which were supplied by private menu collectors.

The team compared the menus, printed between 1928 and 1974, to market surveys of fishermen’s catches in the early 20th century, and also to governmental data collected from around 1950 onward. This allowed the researchers to compare how well the menus reflected the kinds of fishes actually being pulled from the sea.

The menus, their comparative analyses revealed, did indeed closely reflect the varieties and amounts of fish that fishermen were catching during the years that data were available, indicating that the restaurants’ offerings could provide a rough idea of what Hawaii’s fisheries looked like between 1905 and 1950–a period that experienced no official data collection.

Prior to 1940, the researchers report in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, reef fish, jacks and bottom fish commonly turned up on menus. These include pink snapper, green snapper and amberjack. But that quickly changed after Hawaii received its statehood in 1959. By then, those once popular fishes appeared on fewer than 10 percent of menus. Some, such as Hawaiian flounder, Hawaiian grouper and Hawaiian barracuda disappeared from menus completely after 1960. In their place, large-bodied pelagic species, or those that live in deep open water such as tuna and swordfish, began to turn up served with a wedge of lemon. By 1970, these large pelagic fishes were on nearly every menu the team examined.

Diners’ changing tastes and preferences may explain part of this shift away from the nearshore and out to the deep sea, but the researchers think there is more to the story than foodie trends alone. Instead, this sudden shift likely reflects a decline in nearshore fish populations. Because both the early and later menus corroborate well with known fisheries data, the 1930s and 40s menus likely represent a boom in nearshore fisheries, with the 1950s menus standing in as a canary in the coal mine signaling the decline of those increasingly gobbled-up populations. “This helps us to fill in a large gap–between 1902 and 1948–in the official fishery records,” Van Houtan said in an email. “But it also shows that by the time Hawaii became a U.S. state, its inshore fish populations and reefs were in steep decline.”

Those species that disappeared from menus more than a century ago are still present today, but their populations around Hawaii remain too low to support targeted commercial fishing. Some of them are considered ecologically extinct, meaning that their abundance is so low that they no longer play a significant role in the environment. While a few of those species have returned to Hawaiian menus recently, they are usually imported from Palau, the Marshall Islands or the Philippines, rather than being fished from Hawaiian waters.

The menu trick can’t work for every animal in the sea. Populations dynamics of some species, such as shrimp and mollusks, cannot be inferred from the menus since those animals mostly came from mainland imports. On the other hand, other species, the researchers know, were fished at that time but are not reflected in the menus. Sea turtles, for example, used to be harvested commercially, but they were butchered and sold at local markets rather than at tourist trap restaurants.

Investigating past populations of turtles was in fact the motivation for this project. “Green turtles here nearly went extinct in the early 1970s, and lots of blame was put on increasing tourism and restaurant demand,” Van Houtan explains. He decided to examine just how much restaurants contributed to that near-miss for the green turtles, so he started collecting menus. However, he says, “we were in for a surprise.”

He and his colleagues first got ahold of 22 menus from the early 1960s, only to find that not a single listed turtle soup, turtle pie, turtle stir-fry or any other turtle-themed recipe. He found another 30, then 25 and then 40 menus. By this time, he was 100 menus deep, and had found only a single mentioning of turtle anything. “By doing much background research on the fishery, we discovered turtles were sold over-the-counter at fishmongers and meat markets in Chinatown and other open air markets in Honolulu,” he says. The restaurants, in other words, were not to blame–at least not for the turtles.

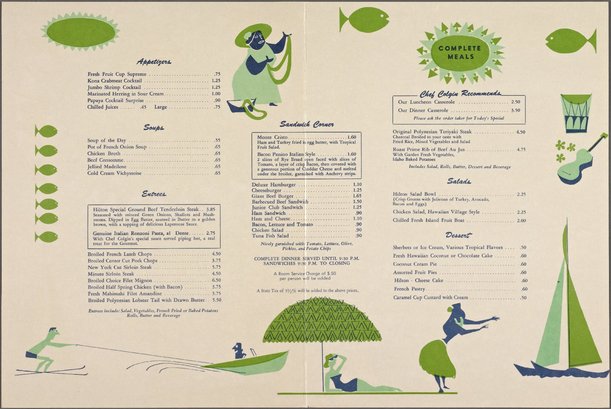

A menu from the Hilton Hawaiian Village, circa 1965. Care for some Kona crabmeat or a jumbo shrimp cocktail for $2? Photo via New York Public Library

Left with all of these menus, however, the team decided to take a closer look into the marine life listed there. “When I assembled those data, it became a story of its own, helping to fill a significant gap in our official government records,” he says.

Collecting all of those menus, he adds, was no small task. He hustled between appointments with Hawaiiana experts, archivists, publishers, Hawaiian cooking historians, tourism historians, museums and libraries. But some of the more pedestrian venues proved most useful, including eBay collectors who would occasionally invited Van Houtan over to dig through boxes of hoarded menus. “I met a lot of interesting people along the way,” he says.

Scientists often turn to historic documents, media stories, artwork, photographs or footage to infer past events or trends. And while researchers have used menus to track a seafood item’s popularity over time, not many think to use dining data as a proxy for fish population abundance. The most interesting thing about the study, Van Houtan thinks, is “not that we used menus as much as that no one previously thought to.”

That, he says, and a few of the more odd-ball items that turned up on some of the old menus, like magnesium nitrogen health broth. “I have no idea what that was,” he says. “And pineapple fritters with mint sauce doesn’t sound very yummy to me either!”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)