Walk This Way

Humans’ two-legged gait evolved to save energy, new research says

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/upright_group.jpg)

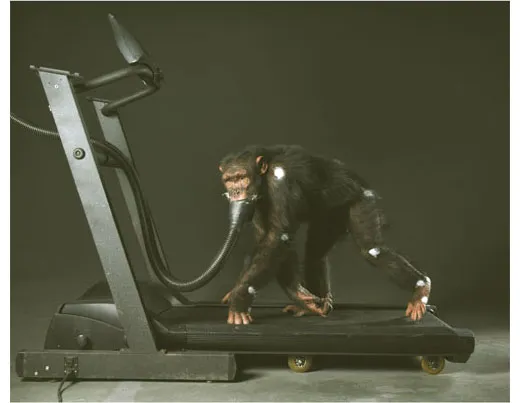

A treadmill experiment is giving anthropologists runaway evidence about evolution: early human ancestors may have started walking upright because the process conserves energy compared with the four-limbed knuckle-walking of chimpanzees.

Researchers have debated why hominids began walking with two legs sometime around six million years ago—when the key characteristic distinguishing them from their last ape ancestors emerged. Some have espoused the energy-conservation theory—in part because the cool, dry climate during the Miocene could have separated food patches by great distances. Others have argued postural reasons for the change, suggesting that an upright stance enabled ancestral humans to see above tall grass and spot predators, or to reach for fruit in trees or bushes.

Previous comparisons of two- versus four-legged walking have produced inconclusive results. One study involving juvenile chimps found that the apes spent more energy than humans did while walking, but many researchers felt that the costs would change with adult apes. A recent study of macaques found that two-legged walking took higher energetic tolls, but monkeys—unlike chimps—don't habitually stroll upright.

In the new analysis, a group of researchers from three universities gathered data on the energy expended by four people and five adult chimps as they walked on a treadmill; the chimps walked upright and on all fours. The researchers measured respiration, angles of movement, positions of critical joints and the force each limb put on the ground.

People used about 25 percent less energy than chimps did, regardless of which style the apes walked, the group reports in the July 24 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In addition, anatomical models of people and apes in different walking stances accurately predicted this cost difference.

"It's profoundly important data on the origin of why we started [walking on two legs]," says biological anthropologist Daniel E. Lieberman of Harvard University, who was not affiliated with the study. To put the energy figure in perspective, he says, people spend about 30 percent more energy running than they do walking.

"If we were to walk like a chimp, it would cost us basically what it costs to go running," he says. "[Upright walking] saves you a lot of energy."

Taking the group of chimps as a whole, the researchers found no difference in energy cost between the walking styles. But it's not surprising that two-legged walking costs chimpanzees a lot of energy, says study co-author Herman Pontzer of Washington University in St. Louis, because the apes walk upright with their knees bent—imagine walking all day in a skiing position—and have short hind legs. These two traits require lots of energy to compensate for.

Perhaps most importantly, the chimp with the most human-like gait and body type walked upright more efficiently than he knuckle-walked—a finding that Pontzer calls a snapshot of how this evolution may have taken place.

"Because we understand the mechanics [of walking], we could see what evolution could tinker with to make it less expensive," Pontzer says. Such alterations include straightening the knees and lengthening the legs.

The appearance of these traits in one ape suggests enough variation in the population for natural selection to have taken hold if necessary, Lieberman says. If the environment caused apes to walk a lot farther, the high energetic cost of knuckle-walking could have changed the behavior over time.

"That's how evolution works," Lieberman says. "One [chimp] turned out to be better than the other chimps, because he adapted a more extended posture."

Though the fossil record does not extend back to when scientists believe the human-chimp split occurred, several leg and hip bones from later time periods—in particular a hip bone three million years old—reflect the changes that decrease the cost of two-legged walking.

"At least by three million years ago," Lieberman says, "hominids figured out how to not have this [energy] cost."

Smithsonian.com's reader forum

Posted July 16, 2007

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)