Trials of a Primatologist

How did a renowned scientist who has done groundbreaking research in Brazil run afoul of authorities there?

At seven o'clock in the morning on june 15, 2007, the bell rang at the front gate of Marc van Roosmalen's modest house on the outskirts of Manaus, Brazil. For van Roosmalen, a Dutch-born primatologist and Amazon adventurer who had been chosen one of Time magazine's "Heroes for the Planet" in 2000, that was a somewhat unusual event: visitors had lately become scarce. The 60-year-old scientist was dwelling in semi-isolation, having separated from his wife, become estranged from his two sons, lost his job at a Brazilian research institute and been charged with a raft of offenses, including misusing government property and violating Brazil's biopiracy laws. But things had begun to turn around for van Roosmalen: he had been exonerated in three successive trials and had even begun to talk optimistically about getting his old job back. In July, he was planning to travel on a research vessel up the Rio Negro, the Amazon's main tributary, with a group of biology students from the United States, his first such trip in years.

Van Roosmalen buzzed open the compound gate, he told me recently. Moments later, he said, five heavily armed federal police officers burst into the garden, bearing a warrant for his arrest. Then, as his 27-year-old Brazilian girlfriend, Vivi, looked on in horror, van Roosmalen says, police cuffed his hands behind his back and placed him in the back seat of a black Mitsubishi Pajero. Van Roosmalen asked where they were heading. It was only then, he says, that he learned that he had just been found guilty, in a criminal procedure conducted in his absence, of crimes ranging from keeping rare animals without a permit to illegal trafficking in Brazil's national patrimony, to the theft of government property. The sentence: 14 years and 3 months in prison.

Van Roosmalen's immediate destination was the Manaus public jail, a decrepit structure in the city center built at the height of the Amazon rubber boom a century ago. Regarded by human-rights groups as one of Brazil's most dangerous and overcrowded jails, it is filled with some of the Amazon's most violent criminals, including murderers, rapists, armed robbers and drug traffickers. According to van Roosmalen, he was tossed into a bare concrete cell with five other men considered likely to be killed by other inmates. His cellmates included two contract killers who spent their days in the windowless chamber smoking crack cocaine and sharing fantasies of rape and murder. Lying in his concrete bunk after dark, van Roosmalen would stare up at the swastika carved into the bunk above his, listen to the crack-fueled rants of his cellmates and wonder if he would survive the night. John Chalmers, a 64-year-old British expatriate who visited van Roosmalen in jail in July, says he found the naturalist "in terrible shape: drawn, haggard, depressed. He was telling me how he'd seen prisoners have their necks snapped in front of him. He was frightened for his life."

For van Roosmalen, the journey into the depths of the Brazilian prison system marked the low point of a terrible fall from grace. At the height of his career, just five years earlier, the scientist had been hailed as one of the world's most intrepid field naturalists and a passionate voice for rain forest preservation. In his native Holland, where he is a household name, he received the country's highest environmental honor, the Order of the Golden Ark, from the Netherlands' Prince Bernhard, consort to Queen Juliana, in 1997; the National Geographic documentary Species Hunter, filmed in 2003, celebrated his adventurous spirit as he trekked up remote Amazonian tributaries in search of rare flora and fauna. Van Roosmalen claimed to have identified seven never-before-seen species of primates—including a dwarf marmoset and a rare orange-bearded titi monkey—along with a collarless, piglike peccary and a variety of plant and tree species. He had used these discoveries to promote his bold ideas about the Amazon's unique evolutionary patterns and to give momentum to his quest to carve these genetically distinct zones into protected reserves, where only research and ecotourism would be allowed. "Time after time after time, [van Roosmalen has contributed to] this sense that we're still learning about life on earth," says Tom Lovejoy, who conceived the public television series Nature and today is president of the H. John Heinz III Center for Science, Economics and the Environment in Washington, D.C.

But van Roosmalen's passions ultimately proved his undoing. Observers say he became trapped in a web of regulations meant to protect Brazil against "biopiracy," loosely defined as the stealing of a country's genetic material or live flora and fauna. Brazil's determination to guard its natural resources dates back to the 19th century, when Sir Henry Wickham, a British botanist and explorer, smuggled out rubber-tree seeds to British Malaya and Ceylon and, as a result, precipitated the collapse of Brazil's rubber industry. Critics say the thicket of anti-piracy rules set up by the government has created frustration and fear in the scientific community. At a biologists' conference in Mexico this past July, 287 scientists from 30 countries signed a petition saying that van Roosmalen's jailing was "indicative of the trend of governmental repression in Brazil," and "will...have a deterrent effect on international collaborations between Brazilian scientists and their bio-partners worldwide." The petitioners called the sentence excessive and argued that "for a man of Dr. van Roosmalen's age, temperament and condition [it] is tantamount to a death sentence." One of the scientists told the New York Times: "If they can get him on trumped-up charges, they can get any of us." The Times ran a report on van Roosmalen's incarceration last August, three weeks after he was released from jail on a habeas corpus ruling pending an appeal of his conviction.

"Amazonas is the Wild West, and van Roosmalen was one of the loudest voices against deforestation," says one American biopiracy expert who has followed the case closely. "He became a thorn in the side of local authorities." For their part, Brazilian officials insist that the punishment fit the crime. "Van Roosmalen had so many problems, so it was not possible to make the sentence soft," says Adilson Coelho Cordeiro, chief inspector in Manaus for IBAMA, Brazil's equivalent of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. "Brazil followed the letter of the law."

Indeed, according to colleagues and family members, van Roosmalen's wounds were at least partially self-inflicted. They paint a portrait of a man whose pursuit of the wonders of nature led, as it did with zoologist Dian Fossey of Gorillas in the Mist, to an unraveling of his human relationships. Van Roosmalen, they say, repeatedly bent the rules and alienated politicians, peers and underlings. Then, as his life became engulfed in a nightmare of police raids, prosecutions and vilifications in the press, the scientist turned against loved ones as well. In the end, he found himself friendless, isolated and unable to defend himself—the lonely martyr that he has often made himself out to be. "These fantasies that everybody is out to destroy him, these things are only in his head," says Betty Blijenberg, his wife of 30 years whom he's now divorcing. "I would tell him to keep quiet, but he would never listen. And this created big problems for him."

I met Marc van Roosmalen for the first time on a sultry November morning in the lobby of Manaus' Tropical Business Hotel, three months after his release from jail. The scientist had been keeping a low profile while waiting for his appeal to be heard by Brazil's high court, turning down interviews, but he had grown impatient and decided to break his silence. He even suggested that we spend several days on a friend's riverboat heading up the Rio Negro, to talk in privacy while immersed in the environment he loves.

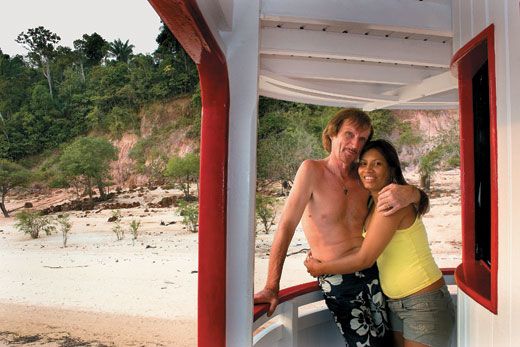

Van Roosmalen walked into the hotel, an 18-story tower overlooking the wide Rio Negro, wearing a tattered T-shirt, jeans and hiking boots. He reminded me of an aging rock star venturing tentatively back on tour: his blond hair hung in a shag cut; a goatee and droopy blond mustache framed his drawn face; and a fine pattern of wrinkles was etched around his pale blue eyes. The trauma of his recent incarceration had not worn off. There was still a wounded-animal quality to the man; he approached me cautiously, holding the hand of Vivi, Antonia Vivian Silva Garcia, whose robust beauty only made her companion seem more hangdog. Van Roosmalen had begun seeing her in 2003, shortly after they met in a Manaus beauty salon owned by her brother; the relationship, revealed to van Roosmalen's wife by their 25-year-old son, Tomas, precipitated the breakup of his marriage and the disintegration of his personal life just as his career was falling apart. Van Roosmalen now clung to Vivi as his one unwavering source of support. He told me that she had brought him food in jail, found new lawyers for him and kept his spirits up when he was feeling low. "I owe her my life," he says.

As we sat in the hotel coffee shop sipping Guarána, a soft drink made from the seed of an Amazonian fruit, van Roosmalen spoke ruefully about what he repeatedly called "my downfall." The Brazilian press, he said, "is calling me the ëbiggest biopirate of the Amazon.'" He reached into a briefcase and extracted a photocopy of a letter he'd prepared for the press during his incarceration but hadn't made public until now. The handwritten screed called the cases against him, begun in 2002, a politically motivated "frame" job and lashed out at the Brazilian government led by populist president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. "The best way to unite Brazil's masses is to create a common enemy that is easy to distinguish," van Roosmalen had written. "Who better to pick as a target, as a symbol of the biopiracy evil, than the Dutch gringo?" In the letter he questioned "whether I will get out of [jail] alive...to tell the world the truth." It was, I thought, exactly the kind of inflammatory document that would likely infuriate the very people he needed most—and undermine his efforts at exoneration.

The mood lightened a bit later, when, in the torpid heat of the Amazonian afternoon, we boarded the Alyson, a 60-foot riverboat, for our three-day journey up the Rio Negro and back. Van Roosmalen, Vivi and I stood at the stern of the vessel owned by their friend John Chalmers—an affable, beer-bellied expat from the British Midlands who'd left his tropical-fish business in his son's hands and settled in Manaus in 2002. Chalmers shouted orders in broken Portuguese to his three-man crew. The skyline of Manaus receded, and the vessel motored at eight knots past long sandy beaches (still studded with millennium-old pottery shards from the original Indians who lived on the banks) and unbroken jungle. It was the first time in several years, van Roosmalen told me, that he had ventured upriver.

Over the hum of the engine and the singsong Portuguese of Chalmer's Brazilian partner, Ana, the boat's cook, van Roosmalen provided an enthusiastic commentary on the world around us. "The banks here are all covered in igapó forest," he said—tough, willow-like trees genetically adapted to survive in an environment that lies underwater four to six months of the year. We were motoring, he pointed out, past some of the most pristine rain forest left in Brazil: almost all of Amazonas state's jungle is still standing, in contrast to those of other Amazon states, which have steadily been cut down to make way for soybean and sugar plantations. "But all this is now at risk," he said. Two years ago, devastating forest fires ignited all over the Amazon, including around Manaus, casting a gray pall over the city and burning for two weeks before dying out. "Every year, because of global warming, the dry season is starting earlier and becoming more prolonged," he said. "If we have two straight years like 2005, when the slash-and-burn fires went out of hand, then it's quite possible that huge tracts of the rain forest will never come back."

Van Roosmalen's early years gave little hint of the mess his life would become. He grew up in Tilburg in southern Holland, where his father was a chemist; the family took road trips across Europe every summer—visiting museums, exploring forests and beaches. "My brother and I were ornithologists, and we caught snakes and amphibians, took them home and put them in aquariums. And I always had a dream to keep a monkey as a pet," van Roosmalen told me. It was early evening, and we had cruised to the far side of the river, laying anchor at the mouth of a 25-mile-long channel that joined the nutrient-rich Amazon to the Rio Negro, a "black water" river low on nutrients and thus nearly devoid of animals and insects. In the still of the mosquito-less night, Ana carried platters heaped with shrimp and rice to the top deck, where we sipped iced caipirinhas, Brazil's national drink, and listened to the splash of a lone flyingfish in the bathlike water.

At 17, van Roosmalen began studying biology at the University of Amsterdam, moved into a houseboat on a canal and filled it with lemurs from Madagascar, South American spider monkeys and marmosets he'd purchased in a neighborhood pet shop. (This was well before the 1975 Geneva Convention declared that all primates were endangered species and made their trade illegal.) "I built another room for my monkeys, and I had no real neighbors, otherwise it would have been difficult, with the monkeys escaping all the time," he said. In 1976, with his young wife, Betty, a watercolorist and animal lover he'd met in Amsterdam, and infant son, Vasco, van Roosmalen set off to do doctoral fieldwork on the feeding patterns of the red-faced black spider monkey in the jungles of Suriname, a former Dutch colony in the northeast of South America.

Betty Blijenberg remembers their four years in Suriname—"before Marc became famous and everything changed"—as an idyllic period. The couple constructed a simple house on Fungu Island deep in the interior; van Roosmalen left the family at home while he ventured alone for months-long field trips around the Voltzberg, a granite mountain that rises above the canopy and affords a unique view of the top of the rain forest. "You could feel the breeze of evolution in your neck there," he now recalled. In a pristine jungle replete with jaguars, toucans, macaws and various species of primates, the young primatologist lived alongside a troop of spider monkeys, often eating the fruits that they left behind in the forest. He survived two near-fatal bouts of malaria and a paralyzing spider bite, which put an end to his walking barefoot down jungle trails. Van Roosmalen came to see the fruit-eating spider monkeys as a key link in the evolutionary chain—a highly intelligent creature whose brain is imprinted with the complex fruiting and flowering cycles of at least 200 species of trees and lianas (tropical vines). "The spider monkeys are the chimps of the New World," he told me. After two years of work in French Guiana, van Roosmalen collated his research into a groundbreaking book, Fruits of the Guianan Flora, which led in turn to his being hired in 1986 by the Brazilian Research Institute for the Amazon (INPA), the country's leading scientific establishment in the Amazon, based in Manaus.

There van Roosmalen initially thrived. With his good looks, boundless energy, high ambition, prolific publishing output and talent for mounting splashy field trips funded by international donors, he stood out in an institution with its share of stodgy bureaucrats and underachievers. He launched a nongovernmental organization, or NGO, dedicated to carving out wilderness preserves deep in the Amazon and, initially with the backing of officials at IBAMA, began caring for orphaned baby monkeys whose parents had been killed by hunters; he ran a monkey breeding and rehabilitation center in the jungle north of Manaus, then began operating a smaller facility in his own Manaus backyard. Even after Brazil tightened its laws in 1996, mandating an extensive permitting process, van Roosmalen says IBAMA officials would often bring him orphaned animals that they had retrieved from the jungle.

Eventually, however, van Roosmalen's iconoclastic style bred resentment. In a country where foreigners—especially foreign scientists—are often regarded with suspicion, his pale complexion and heavily accented Portuguese marked him as an outsider, even after he became a naturalized Brazilian citizen in 1997. Colleagues were irked by van Roosmalen's habit of failing to fill out the cumbersome paperwork required by the institute before venturing into the field. They also questioned his methodology. For example, says Mario Cohn-Haft, an American ornithologist at INPA, he often based his findings of a new species on a single live, orphaned monkey, whose provenance could not be proved and whose fur color and other traits might have been altered in captivity. Louise Emmons, an adjunct zoologist at the Smithsonian Institution, characterizes van Roosmalen's discovery of a new species of peccary as "not convincing scientifically," and Smithsonian research associate Daryl Domning questions his "discovery" of a dwarf manatee on an Amazon tributary. "There's no doubt at all in my mind that his 'new species' is nothing but immature individuals of the common Amazonian manatee," says Domning. "This is even confirmed by the DNA evidence he himself cites."

But Russell Mittermeier, the founder and president of Conservation International, an environmental organization based in metropolitan Washington, D.C., holds van Roosmalen in high professional regard. "There is nobody in the world who has a better understanding of the interaction between forest vertebrates—especially monkeys—and forest plants," says Mittermeier, who spent three years with van Roosmalen in Suriname in the 1970s. "Marc's discoveries of new species in the Amazon are exceptional, and his knowledge of primate distribution and ecology in the Amazon is excellent."

Van Roosmalen also attracted scrutiny by offering donors, through his Web site, the opportunity to have a new monkey species named after them in exchange for a large contribution to his NGO. In recognition of Prince Bernhard's efforts on behalf of conservation, van Roosmalen decided to call an orange-bearded titi monkey he'd discovered Callicebus bernhardi. The prince made a sizable contribution. Although the practice is not uncommon among naturalists, colleagues and officials accused van Roosmalen of profiting improperly from Brazil's natural patrimony. Van Roosmalen used the funds he had raised to purchase land deep in the jungle in an attempt to create a Private Natural Heritage Reserve, a protected swath of rain forest, but IBAMA refused to grant him the status; some officials at the agency charged that he planned to use the park to smuggle rare monkeys abroad. Van Roosmalen shrugged off the criticism and ignored warnings from friends and family members that he was setting himself up for a fall. "In the best light he was naive, he didn't seem to know how to protect himself," says Cohn-Haft, who arrived at INPA about the same time as van Roosmalen. "In the worst light he was stepping on people's toes, pissing people off and getting himself in trouble. Some people saw him as doing sloppy science, others as arrogant, and [his attitude was], 'to hell with all of you, let me do my work.'"

Late on the morning of our second day on the Rio Negro, under a broiling sun, van Roosmalen steered a skiff past leaping pink river dolphins, known as botos. After years of enforced inactivity, the naturalist was unofficially back in the role he loved, chasing down leads from locals in pursuit of potential new species. An hour earlier, van Roosmalen had heard rumors in an Indian village about a rare, captive saki monkey with distinctive fur and facial patterns. "We've got to find it," he'd said excitedly. Each new species he discovered, he explained, provided more support for the "river barrier" hypothesis proposed by his hero, famed Amazon explorer Alfred Russel Wallace, in 1854. "You have to see the Amazon basin as an archipelago—a huge area with islandlike areas, cut off genetically from one another," van Roosmalen had told me earlier, expounding on his favorite scientific theme. "It's like the Galápagos. Each island has its own ecological evolution."

The skiff docked beside a riverside café, and we climbed out and followed the proprietor, a stout, middle-aged woman, into a trinket shop in back. Tied up by a rope was one of the oddest creatures I'd ever seen: a small, black monkey with a black mane that framed a peach-colored face shaped like a heart, with a sliver of a white mustache. Van Roosmalen beckoned to the saki monkey, which obligingly leapt onto his shoulder. The naturalist gazed into its face and stroked its mane; the saki responded with squeaks and grunts. "If you come onto these monkeys in the forest they freeze, and they don't come to life again until you leave the area," he said, studying the saki admiringly. Van Roosmalen paused. "It's an orphan monkey that somebody brought here," he said. "It's not like Africa. They don't put the baby in the pot with the mother, they sell it." The saki grabbed van Roosmalen's necklace made of palm-seeds and used its sharp canines to try to break open the rock-hard nuggets, gnawing away for several minutes without success.

Van Roosmalen was disappointed: "This saki should be distinct, because it's such a huge river, but it looks superficially like the male population on the other side of the Rio Negro," he said. Perhaps local Indians had introduced the Manaus saki monkeys to this side of the Rio Negro long ago, and the animals had escaped and carved out a new habitat. He conferred with the monkey's owner, who rummaged through the monkey's box filled with shredded paper and came up with a handful of dried brown fecal pellets. Van Roosmalen stuffed the pellets into the pocket of his cargo pants. "I'll run a DNA sampling when we get home," he said, as we climbed back into the skiff and sped back toward the Alyson.

It was on an excursion not so different from this one that van Roosmalen's career began to self-combust. On July 14, 2002, van Roosmalen told me, he was returning from a jungle expedition aboard his research vessel, the Callibella, when a team of Amazonas state agents boarded the boat. (Van Roosmalen said he believes they were tipped off by a jealous colleague.) The authorities seized four baby orphaned monkeys that van Roosmalen was transporting back to his Manaus rehabilitation center; the scientist lacked the necessary paperwork for bringing the monkeys out of the jungle but believed he had properly registered the research project years earlier. Van Roosmalen was accused of biopiracy, and interrogated during a congressional investigation. At first, recalls son Vasco, 31, INPA's director rushed to his defense: then, "Marc started criticizing his INPA colleagues in the press, saying 'everybody is jealous of me'—and INPA's defense faltered." Van Roosmalen's bosses at INPA convened a three-man internal commission to investigate a host of alleged infractions. These included illegal trafficking in animals and genetic material, improperly auctioning off the names of monkey species to fund his NGO and failing to do the mandatory paperwork in advance of his field research.

In December 2002, Cohn-Haft circulated among his colleagues a letter he had written in support of van Roosmalen, accusing the press and the INPA administration of exaggerating his offenses. "I thought there would be a wave of solidarity, and instead I saw very little response," Cohn-Haft told me. "People said, 'Don't put your hand in the fire for this guy. It's more complicated than you think.'" Months later, two dozen IBAMA agents raided van Roosmalen's house, seizing 23 monkeys and five tropical birds. Van Roosmalen was charged with keeping endangered animals without a license—despite the fact, he argued, that he had applied for such a permit four times in six years without ever receiving a response. Cohn-Haft calls IBAMA's treatment of him unfair. "Marc really cares about these creatures," he says. "If you are receiving monkeys from the same agency that is giving out permits, you figure that these people aren't going to stab you in the back." Four months later, on April 7, 2003, van Roosmalen was fired from his INPA job.

Abandoned by the research institute that had supported him for years, van Roosmalen told me that he then found himself especially vulnerable to Brazilian politicians and prosecutors. He was accused of theft and fraud in a 1999 arrangement with a British documentary production company, Survival Anglia, to import five tons of aluminum scaffolding for use on a jungle film project. To qualify for a waiver on import duties, the company had registered the scaffolding as the property of INPA; but then, the authorities charged, van Roosmalen illegally used it after the films were shot to make monkey cages for his breeding center. Russell Mittermeier and other influential U.S. scientists urged van Roosmalen to accept a deal they heard the Brazilian authorities were proffering. Recalls Vasco: "INPA would receive the [confiscated] monkeys and my father would cede the cages that were made of parts of the scaffolding. But he ignored that deal, he continued to criticize IBAMA, and everybody else."

It was about this time, according to van Roosmalen, that his younger son, Tomas, told his mother about the photographs of Vivi. Shortly after, van Roosmalen moved out of the house. At almost the same time, the board of van Roosmalen's NGO, which included the three members of his immediate family and four native-born Brazilians, voted to remove him as president, citing such administrative irregularities as his failure to submit financial reports. The board seized the NGO's bank account, research vessel and Toyota Land Cruiser. "We went by the book," says one board member.

Ricardo Augusto de Sales, the federal judge in Manaus who handed down the June 8 verdict against van Roosmalen, imposed, says van Roosmalen, the harshest possible punishment: two years for holding protected species without a permit, and 12 years and 3 months for "appropriating" Brazil's "scientific patrimony" (the scaffolding) and using it for "commercial gain." According to Vasco, his father's lawyer had not been paid in years and thus provided no defense. "All [the judge] had was the prosecutor's version." (Van Roosmalen's attorney declined to comment.)

After van Roosmalen went to jail, says Vasco, his wife and Marc's eldest brother, who had come from Holland to help, rushed to Manaus to hire new lawyers and try to get him freed pending an appeal; Vivi also brought lawyers, who, according to Vasco, submitted "a hastily written, one-page appeal" to the high court in Brasilia, the capital. At the same time, Betty Blijenberg, who had done social work for five years at the jail and knew the staff, begged the director to move her husband to a solitary cell. "I knew he was in danger, they were going to kill him, he couldn't defend himself. I asked him, 'Why is he there? Why is he not in a separate cell?' The director said, 'There's nowhere else to put him.'" Van Roosmalen believed he was in grave peril: he says he was told that inmates had purchased crack cocaine from the jailhouse "sheriff," a convicted murderer, paying for it by "billing" van Roosmalen's prison "account." He was also told that he needed to come up with about $1,000 to pay off the debt or he would be killed; van Roosmalen's attorneys ultimately lent him the cash. After one month, his attorneys managed to get him moved to a military garrison while Judge de Sales was on holiday; but after five days, the judge returned and ordered him back to the public jail, arguing that van Roosmalen was not entitled to privileged treatment. Fifty-seven days into his ordeal, with the Brazilian government under pressure from the Dutch Foreign Ministry, the scientific establishment and the international media, a federal court in Brasilia set van Roosmalen free.

Vasco traces his father's downfall to "a number of disconnected actions by individuals, rather than a big conspiracy." Cohn-Haft agrees. "It's not The Pelican Brief," he says. "It's about a bunch of crappy people finding someone they can pick on and picking on him. We're talking hubris on his side. He really thinks that he's some kind of savior. And on the other side, he's being made out to be an enormous villain. And both versions are exaggerated."

But in Marc van Roosmalen's eyes, a vast array of enemies, including his immediate family, are all out to get him. On our final evening on the Rio Negro, the scientist sat at the dinner table on the boat's main deck, his haggard face illuminated by fluorescent lights, and laid out how his foes sought to "get me out of the way" because "I know too much" about corruption and the efforts of big Brazilian interests to destroy the Amazon rain forest. Eyes widening, he singled out his son Vasco as a prime perpetrator. Driven by an "Oedipus complex" and his desire to ingratiate himself with the Brazilian government, van Roosmalen claimed, Vasco had engineered his removal from the NGO, stolen his boat and car and tried to force him to hire a criminal attorney who would deliberately lose the case. "He wanted me to die in prison," van Roosmalen said. He accused his wife, Betty, of conspiring with IBAMA to have him arrested in revenge for his extramarital affair; he lashed out at his former colleagues at INPA as "scavengers." Fellow scientists such as Russell Mittermeier had "turned their backs on me" to protect their own ventures in the rain forest. "They have lots of money at stake," he said. As van Roosmalen ranted on into the night, I had the feeling that I was sitting in some Brazilian version of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. Isolated in the middle of the Amazon jungle and under continuous attack for years, it seemed to me quite possible that the scientist had been infected by a touch of madness. His two months of hell in the Manaus jail, I thought, must have confirmed all of his suspicions about plots and vendettas. Who among us, I wondered, thrown into the same nightmare, could resist finding a common thread of conspiracy winding through our troubles?

The next morning, our last on the Rio Negro, the crew anchored the boat at the base of a cliff, and van Roosmalen, Vivi and I climbed a steep wooden staircase to a nature camp at the edge of the jungle. With a local guide and his two mangy dogs leading the way, we followed a sinuous trail through terre firma vegetation: primary rain forest that, unlike the igapó we'd been exploring, sits high enough above the river to avoid submersion during the rainy season. Van Roosmalen pointed out lianas as thick as large anacondas, and explained how these and other epiphytes (flora, in this setting, that live on other plants in the forest canopy) function as giant vessels for capturing carbon dioxide, and thus play a vital role in reducing global warming. "The total surface of leaves in a rain forest is a thousand, maybe even a million times bigger than the monoculture they want to convert the Amazon into," he told me. Farther down the jungle trail, he showed me a dwarf species of palm tree that captures falling leaves in its basketlike fronds; the decomposing material scatters around the base of the tree and fortifies the nutrient-poor soil, allowing the palm to thrive. "Every creature in the rain forest develops its survival strategy," he said.

Van Roosmalen's own survival strategy had proved disastrously unreliable up to now; but he said he was confident that everything was going to work out. As we walked back through the forest toward the Rio Negro, he told me that if the high court in Brasilia found him innocent, he would sue INPA to get his old job back and try to pick up his old life. If the high court upheld all or part of the sentence, there was "no way" that he would return to jail. Although the Brazilian police had frozen his bank account and seized his Brazilian passport to prevent him from fleeing the country, van Roosmalen assured me, without going into detail, that he had a contingency escape plan. He had job offers waiting for him at academic institutions in the United States, he said. Perhaps he would go to Peru to search for the next Machu Picchu. "I've seen the Landsat pictures, and I know it's out there," he told me. "I'll be the one to find it." We reached the river and climbed aboard the Alyson. Van Roosmalen stood at the railing as the boat puttered downstream, carrying him away from his brief jungle idyll, back toward an uncertain future.

Writer Joshua Hammer is based in Berlin.

Freelance photographer Claudio Edinger works out of São Paulo.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)