These Pictures Give a Rare Glimpse Into the Heart of the Pluto Flyby

Spanning the full 9.5 years of the mission to date, the images by Michael Soluri capture the people behind the epic close encounter

Never before in Earth's history has anyone waited so eagerly to see summer travel photos. This week the Internet exploded with rapture as the New Horizons spacecraft sent back its first close-up images of Pluto and its moons after a 9.5-year, 3-billion-mile road trip.

New Horizons spent part of its voyage in cruise control, hibernating and saving its energy for the big event. Upon waking up last December, its instruments started gathering pictures and other scientific readings as it sped toward Pluto. Then, around 9 p.m. ET on July 14, it relayed its most crucial field note: the spacecraft had survived its delicate flyby maneuver, and its computers are now brimming with new information about this strange, icy world.

Over the next 16 months, data sent back from the encounter will help humans finally get to know the last—and arguably most beloved—classical planet. But while pictures from the spacecraft are dazzling scientists, fine art photographer and author Michael Soluri has been turning his lens on the scientists, flight controllers and engineers, so we can get to know the humans involved in revolutionizing our understanding of the outer solar system.

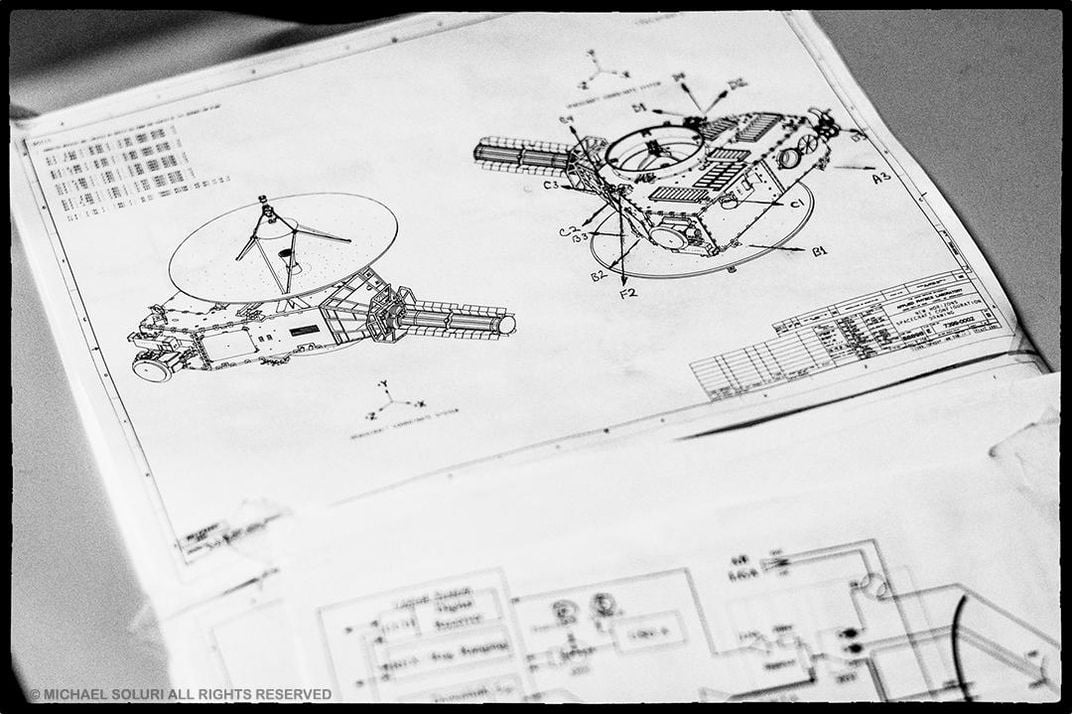

"I have always been struggling to find the humanity in space exploration, on Earth and above," says Soluri. "I brought my sons down to the Air and Space Museum in 1984 or 1985. I took them in, and there was an exact replica of the Viking lander [sent to Mars in 1975]. So we're looking at it, and there's this big robot and I'm seeing all this text, and something's puzzling me: I didn't see the picture of the person who made it possible. And I held on to that for like 20 years."

After a career in fashion photography, followed by work in documentaries and corporate communications, Soluri went looking for a space mission to help him express that humanity. In June 2005, at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, he found New Horizons.

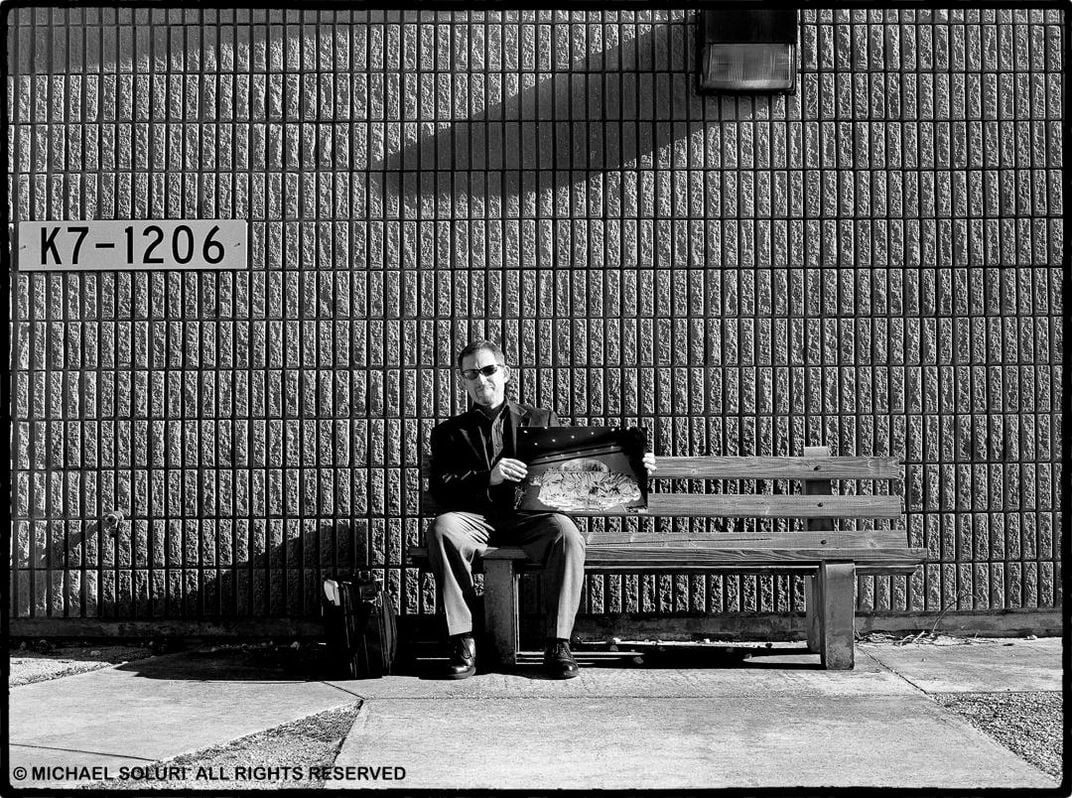

"I explained that I wanted to do an interpretive shot of the probe, and I wanted to backlight it. To me, it was like a piece of sculpture. They said sure, come on down. Then I turned to doing portraits of the people." One of Soluri's images of mission leader Alan Stern ended up in TIME magazine, when Stern was listed as one of the 2007 TIME 100. "And then Alan and I had dinner one night, and he asked if I would be willing to continue doing this all the way through. So the journey has been this weave—every couple of years I would come in and visually sample the mission."

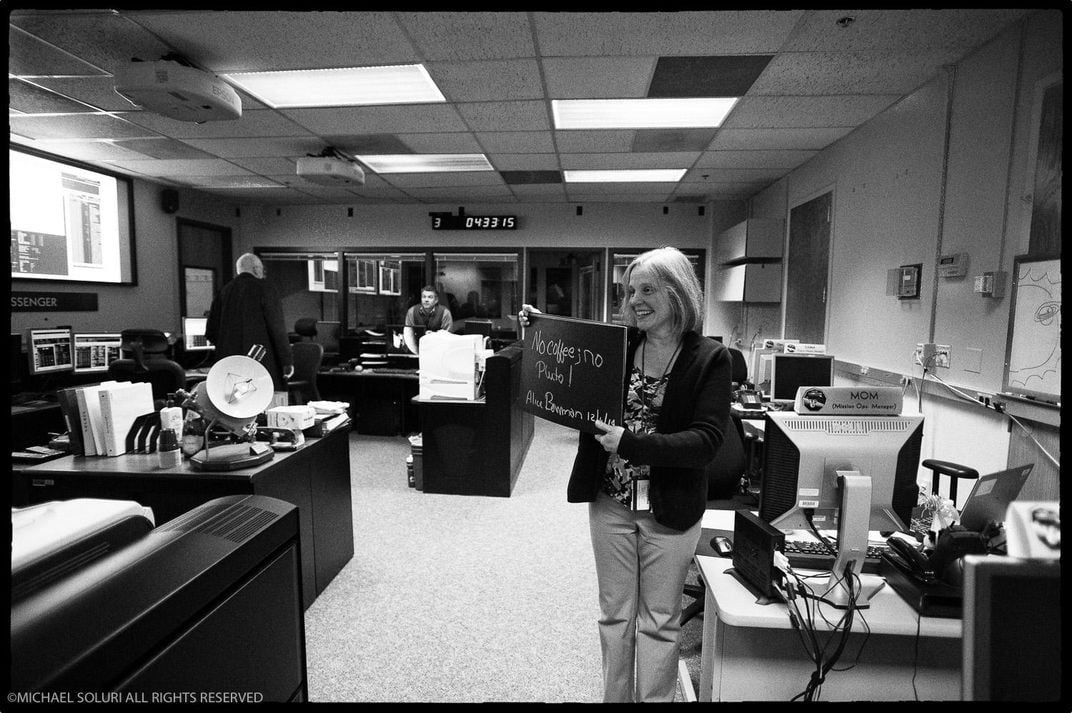

One of his signatures involves asking mission members to write something on a slate that captures how they are feeling at that moment. Like a comic book thought bubble, the technique gives viewers a peek inside the minds of his subjects, adding another layer of connectivity between the viewer and the scientists. One of these shots features mission operations manager Alice Bowman, taken at 1 a.m. the night last December when the spacecraft electronically woke up for the last time before its close approach.

"Everyone was feeling a little woozy. The media had just gone out, so it was me and Mike [Buckley] and Glen [Fountain] of the Applied Physics Lab, and Alice was pushing a coffee cart … so I asked her, tell me something about coffee and Pluto." Her response, seen in the image above, is immediately relatable.

Soluri will be following the New Horizons team for the foreseeable future, but he's also keen to gain the same kind of trust and access to document future space missions that he had for New Horizons and another project documenting the last servicing mission for the Hubble Space Telescope.

"I think James Webb is the next big one," he says, referring to the giant infrared telescope due to launch in 2018, which is billed as the successor to Hubble. "Some of the guys on the New Horizons team will be working on Solar Probe Plus—I'm interested in that." Solar Probe Plus, also slated for a 2018 launch, is designed to dip into the sun's blazing hot corona and solve mysteries about our nearest star. "Just the engineering in building this thing, the shielding … I would love to have the access to be able to do that. But they all present photographic opportunities in seeking and documenting the humanity of space exploration as art."

Note: The gallery above has been updated to include photos from the moment of the spacecraft's closest encounter with Pluto and the moment mission managers received the OK signal from the spacecraft.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1e/ec/1eec9397-a402-44ba-b54a-1ce2f021d21b/nhhyber12614_soluri_sol2891.jpg)