The Story of How An Artist Created a Genetic Hybrid of Himself and a Petunia

Is it art? Or science? With DNA, Eduardo Kac pushes the limits of creativity and ethics

![]()

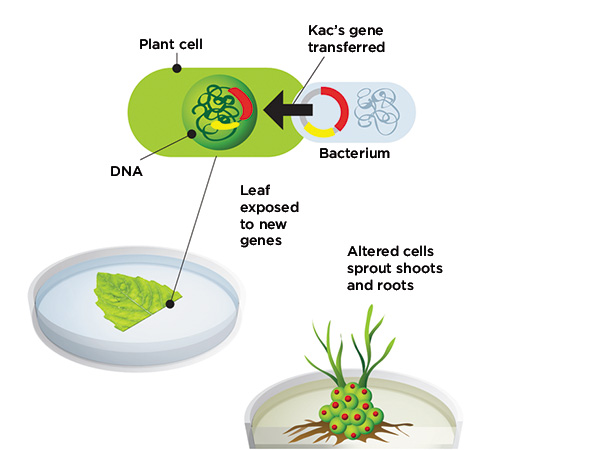

DNA splicing joins one of the artist’s genes (red) and an antibioticresistance gene (yellow) in a bacterium, which inserts the genes into petunia cells. Photo by Eduardo Kac.

The most radical figure in the biodesign movement is Eduardo Kac, who doesn’t merely incorporate existing living things in his artworks—he tries to create new life-forms. “Transgenic art,” he calls it.

There was Alba, an albino bunny that glowed green under a black light. Kac had commissioned scientists in France to insert a fluorescent protein from Aequoria victoria, a bioluminescent jellyfish, into a rabbit egg. The startling creature, born in 2000, was not publicly exhibited, but the announcement caused a stir, with some scientists and animal rights activists suggesting it was unethical. Others, though, voiced support. “He’s pushing the boundaries between art and life, where art is life,” Staci Boris, then a Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, curator, said at the time.

Then came Edunia, the centerpiece of Kac’s Natural History of the Enigma, a work that debuted at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis in 2009. Edunia is a petunia that harbors one of Kac’s own genes. “It lives. It is real, as real as you and I,” says Kac, a Brazil native living in Chicago. “Except nature didn’t make it, I did.”

Still, he had help. The project began in 2003, when the artist had his blood drawn at a lab in Minneapolis. From the sample, technicians isolated a specific genetic sequence from his immune system—a fragment of an immunoglobulin gene that produces an antibody, the very thing that can distinguish “self” from “non-self” and fights off viruses, microbes and other foreign invaders.

The DNA sequence was sent to Neil Olszewski, a plant biologist at the University of Minnesota. In recent years, Olszewski had identified a virus promoter that could control the expression of genes in a plant’s veins. After six years of tinkering, the artist-scientist duo inserted a copy of Kac’s immunoglobulin gene fragment into a common breed of the flower Petunia hybrida.

Antibiotic added to the dish kills cells that did not acquire the foreign genes, while the enhanced plant cells flourish. Illustration by Eduardo Kac.

It’s not the first transgenic plant. A gene from the bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis is routinely introduced to corn and cotton to make the crops insect-resistant. Also, scientists are inserting human genes into plants, in an attempt to manufacture drugs on a large scale; the plants essentially become factories, producing human antibodies used to diagnose diseases. “But you don’t have plants that have been made to explore ideas,” Olszewski says. “Eduardo came to this with an artistic vision. That is the real novelty.”

Kac selected the pink petunia, in large part because of the distinct red veins that hint at his own red blood. And though he refers to his creation as a “plantimal,” that may be overstating the case. The organism has only a minuscule stretch of human DNA amid many thousands of plant genes. Yet it’s the idea of the encounter between the viewer and this curiously endowed plant that mainly interests the artist. Whenever Natural History of the Enigma has been exhibited, Kac has presented Edunia alone on a pedestal, to heighten the drama. “To me, that is pure poetry,” he says.

He predicts that people will have to get more used to strange, genetically engineered hybrids in the future. “Once you are in the presence of this other creature, the world is not the same,” says Kac. “There is no going back.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)