The Macabre Beauty of Medical Photographs

An artist-scientist duo shares nearly 100 images of modern art with a ghastly twist—they’re all close-ups of human diseases and other ailments

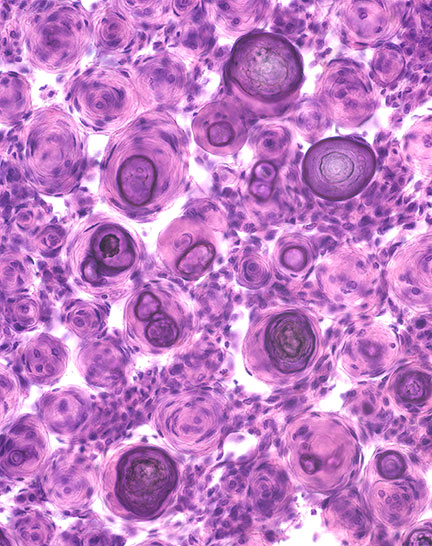

Meneingioma, brain tumor. Image from Hidden Beauty, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

Norman Barker was fresh out of the Maryland Institute College of Art when he got an assignment to photograph a kidney. The human kidney, extracted during an autopsy, was riddled with cysts, a sign of polycystic kidney disease.

“The physician told me to make sure that it’s ‘beautiful’ because it was being used for publication in a prestigious medical journal,” writes Barker in his latest book, Hidden Beauty: Exploring the Aesthetics of Medical Science. “I can remember thinking to myself; this doctor is crazy, how am I going to make this sickly red specimen look beautiful?”

Thirty years later, the medical photographer and associate professor of pathology and art at the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Medicine will tell you that debilitating human diseases can actually be quite photogenic under the microscope, particularly when the professionals studying them use color stains to enhance different shapes and patterns.

“Beauty may be seen as the delicate lacework of cells within the normal human brain, reminiscent of a Jackson Pollock masterpiece, the vibrant colored chromosomes generated by spectral karyotyping that reminded one of our colleagues of the childhood game LITE-BRITE or the multitude of colors and textures formed by fungal organisms in a microbiology lab,” says Christine Iacobuzio-Donahue, a pathologist at the Johns Hopkins Hospital who diagnoses gastrointestinal diseases.

Barker and Iacobuzio-Donahue share in interest in how medical photography can take diseased tissue and render it otherworldly, abstract, vibrant and thought-provoking. Together, they collected nearly 100 images of human diseases and other ailments from more than 60 medical science professionals for Hidden Beauty, a book and accompanying exhibition. In each image, there is an underlying tension. The jarring moment, of course, is when viewers realize that the subject of the lovely image before them is something that can cause so much pain and distress.

Here is a selection from Hidden Beauty:

Alzheimer’s disease. Image from Hidden Beauty, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

Research shows that close to 50 percent of those over 85 years in age have Alzheimer’s, a degenerative neurological disorder that causes dementia. Diagnosing the disease can be tough—the only true test to confirm that a patient has Alzheimer’s is done post-mortem. A doctor collects a sample of brain tissue, stains it and looks for abnormal clusters of protein called amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. In this sample (above) of brain tissue, the brown splotches are amyloid plaques.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus. Image from Hidden Beauty, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

A person’s stomach produces acids to help digest food, but if those acids enter the esophagus, one can be in for a real treat: raging heartburn. Gastroesophageal reflux, in some cases, leads to Barrett’s esophagus, a condition where cells from the small intestine start popping up in the lower esophagus, and Barrett’s esophagus can be a precursor to esophageal cancer. The biopsy (above) of the lining of an esophagus has dark blue cells, signaling that this person has Barrett’s.

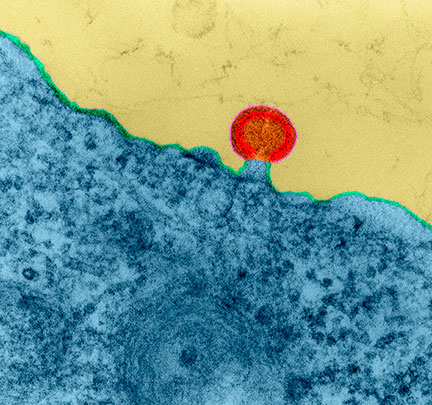

HIV. Image from Hidden Beauty, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

The electron micrograph (above) shows what happens in the circulatory system of someone with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The blue in the image is a white blood cell, referred to as a CD4 positive T cell, and the cell is sprouting a new HIV particle, the polyp shown here in red and orange.

Gallstones. Image from Hidden Beauty, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

This pile (above) of what might look like nuts, fossils or even corals is actually of gallstones. Gallstones can form in a person’s gall bladder, a pear-shaped organ positioned under the liver; they vary in shape and size (from something comparable to a grain of salt to a ping pong ball), depending on the specific compounds from bile that harden to form them.

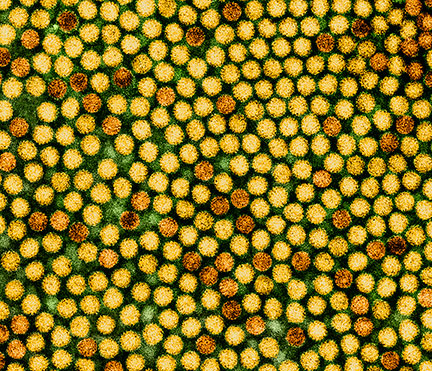

Hepatitis B virus. Image from Hidden Beauty, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

According to estimates, about 2 billion people in the world have Hepatitis B virus (shown above), or HBV. Those who have contracted the virus, through contact with a carrier’s blood or other bodily fluids, can develop the liver disease, Hepatitis B. When chronic, Hepatitis B is known to cause cirrhosis and liver cancer.

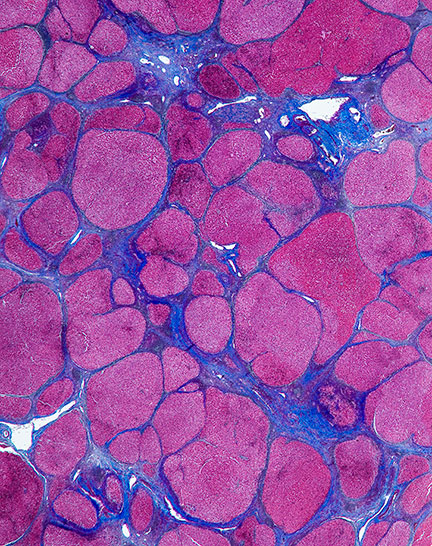

Cirrhosis of the liver. Image from Hidden Beauty, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

When a person develops cirrhosis, typically from drinking alcohol in excess or a Hepatitis B or C infection, his or her liver tissue (shown above, in pink) is choked by fibrous tissue (in blue). The liver, which has a remarkable ability to regenerate when damaged, tries to produce more cells, but the restricting web of fibrous tissues ultimately causes the organ to shrink.

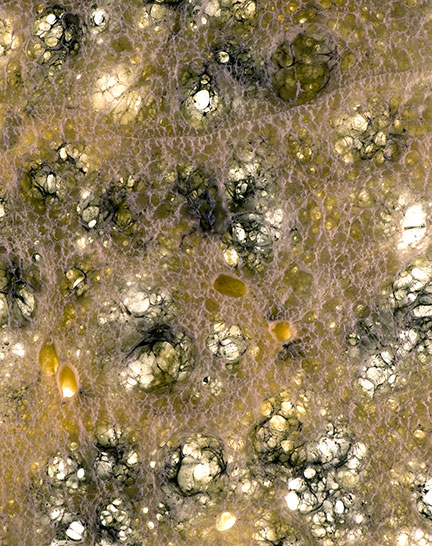

Smoker’s lung. Image from Hidden Beauty, courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

Emphysema (shown above, in a smoker’s lung) is the unfortunate side effect of another unhealthy habit, smoking. With the disease, what happens is that big gaps (seen as white spots in the image) develop in the lung tissue, which disrupt the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide and result in labored breathing. The black coloration on this sample is actual carbon that has built up from this person smoking packs and packs of cigarettes over a stretch of many years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)