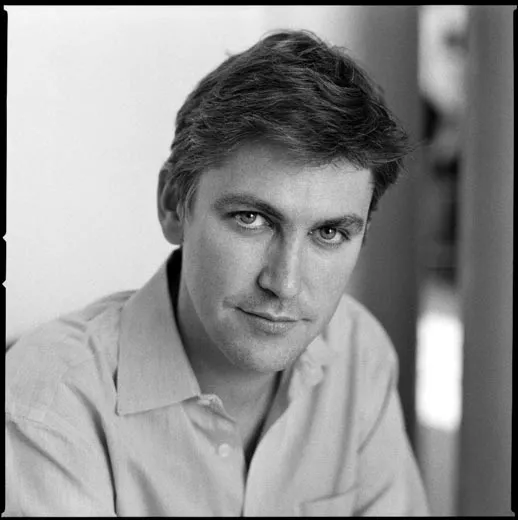

The Inventor of Air

Known for discovering oxygen, scientist Joseph Priestly also influenced the beliefs of our founding fathers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Joseph-Priestley-631.jpg)

Joseph Priestly is best known for discovering oxygen, but Steven Johnson, author of a new biography of Priestly titled The Invention of Air, points out that his contributions were much larger: he was the first ecosystems thinker, almost 200 years ahead of his time. Priestly was best friends with Benjamin Franklin, he wrote about major scientific discoveries in popular literature, and was highly revered by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams.

Johnson’s previous books have covered everything from the impact of popular culture on neuroscience and the19th-century cholera epidemic in London. Smithsonian’s Bruce Hathaway spoke with Johnson about his discoveries in The Invention of Air.

People who recognize the name Joseph Priestly think of him as the discoverer of oxygen. But you say that emphasis completely misses his most important contributions, one of which was the discovery of how plants sustain other life on earth.

The work with oxygen is the one thing I knew about him. And it’s the first line in his biographies everywhere you look. But it’s not entirely true. He wasn’t really the first. Carl Sheele was probably the first. And Priestly was messed up in his understanding of oxygen. Ultimately it was Antoine Lavoisier, in part building on Priestly’s thinking, who got it right about oxygen. It’s possible that if Priestly had not been so much of a polymath that he would have fully understood oxygen. But Priestly was not a systematic thinker. He was a great experimentalist and was incredibly clever at devising these experiments and coming up novel data for people to wrestle with. But he was never particularly gifted at taking the crazy things that he would discover and turning them into a systematic theory of the world. He was interested in finding these weird puzzles and letting other people solve them.

I think one of the things we have to recognize is that there are two kinds of minds in revolutionary science, science that changes the world. There are people who are really good at exploding the existing paradigm and then there are people who once the old paradigms are exploded are good at sorting. Priestly was the former, not the latter. Science needs both kinds of minds.

And you say that Priestly’s great discovery [of oxygen?] was quite a coincidence?

There were a bunch of interesting accidents in Priestly scientific life. One of the big ones was that he once moved randomly next to a brewery. He was ever inquisitive, so he went over to check out what they were doing. He noticed that there were interesting gases coming up from the big vats of beer they were brewing so he asked these guys if he could do some science experiments. What an incredible image. A weird scientist wanting to do experiments over beer.

And due to that fiddling, Priestly invented soda water?

Yes. Just by pouring water back and forth over these vats he noticed that it had a delightful fizzy flavor. So he got interested in gas in part because of this. Priestly’s brother said that when Joseph was like an 11 year old he trapped spiders and mice in little jars and waited to see how long it would take for them to die. So Priestly had long known that if you take a closed, sealed vessel and put an animal in there after a certain amount of time they’re going to use up all the air and they’ll die. But it wasn’t understood why that was happening and what was happening. Were they adding something to the air that was poisoning it? Were they taking something from the air? No one knew just what was happening.

Joseph Priestly suffocating mice and spiders just sounds sadistic. How did any scientific good come out of that?

Priestly had another idea which as far as we know no one had really looked into. What happens with a plant in that jar? How long would it take for the a plant to die? The assumption was that the plant would die; a plant’s another kind of organism. So he took this little sprig of mint out of his garden—and basically all of his nature experiments were done with things that were just around the house, a laundry sink he’d borrowed from his wife and glasses he’d get out of the kitchen. So he puts this mint plant in and isolates and sits around and it doesn’t die. It just keeps growing and growing, and he thinks, hmm, this is interesting.

How did Franklin get involved?

Once [Priestly] decided he’s got something, one of the first people he writes to is Franklin. We don’t have the letter that he writes to Franklin, but we have the letter that Franklin writes back. It’s one of these wonderful things because you have really direct evidence of this conversation that changed the way we think about the world. What Franklin does is he takes the experiment from this very local problem to the global level, in a brilliant way.

It seems from the historical record that Franklin really contributes this to Priestly’s little experiment. What Franklin says is that this sounds like it is a rational system and it’s probably one that exists all across the planet. There must be some way for the Earth to continue to heal itself, to purify the atmosphere. He says it is probably something that is happening everywhere and plants are probably cleaning up the air for us so that we can breathe clean air.

You write that Priestly’s thinking about religion had a major influence on Jefferson. How so?

Priestly did not believe in the divinity of Jesus. He didn’t believe Jesus was God’ son, and didn’t believe in the holy ghost and all that. That’s the founding precept of Unitarianism, that there is one god and there’s a wonderful voice of God’s vision on earth, but that that person is not the son of god. Priestly felt that rather than worshiping shrines and saints and resurrections that the clearest evidence of God’s work on earth was this tremendous advance—of the enlightenment.

What did Priestly see as the most important part of Christianity and how did his views have such a major effect on Jefferson’s?

He thought the essence of Christ’s message was progressive in the sense of doing unto others as you would have them do unto you. He was an early opponent of slavery and things like that. He was a great believer in tolerance. These views had a huge impact on Jefferson. Jefferson famously created the Jefferson Bible where he went through the Bible and eliminated all the parts that were basically supernatural and not Christ’s moral system. And he did that based almost entirely on Priestly’s book, An History of the Corruptions of Christianity.

Because of Priestly’s religious writings, and his political views, for example supporting the French and American revolutions, mobs destroyed Priestly’s house and would have killed him if they’d had the chance. So he emigrated to America. How was he received here?

He was greeted as a hero. He had tea with Washington a couple times, and Adams and Jefferson referred to Priestly 52 times (to Franklin only five times and to Washington only three) in the famous exchange of letters at the ends of their lives. The founding fathers’ intellectual makeup was such that it was impossible for them to imagine separating the insights and understandings of science and technology—they were also very very interested in technology—from their views of society and their politics. They understood that all those things were connected in all kinds of immensely interesting ways.

You write that Priestly’s views were important to the founding fathers. How so?

In some ways their vision of progress and their belief in the possibility for change, for improvement of human society, had come out of the progress that they had seen and that Priestly had celebrated so much in his writings on scientific and technological advancements over the preceding century and a half. So the idea was that if we can understand so much about the world and about electricity and about air and all these different new fields, why can’t we apply that same kind of rational, empirical method to the organization of human society? One of the messages of this book is that this kind of thinking wasn’t just a dalliance that the founding fathers had on the side but rather that their worldviews were thoroughly infused with the march of science and that partially their political views came out of that tradition.