The Hawks in Your Backyard

Biologists scale city trees to bag a surprisingly urban species, the Cooper’s Hawk

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Coopers-Hawk-Bob-Rosenfield-631.jpg)

Bob Rosenfield stares up into the high canopy of a Douglas fir in Joanie Wenman’s backyard, in the suburbs of Victoria, British Columbia. “Where’s the nest again?” he asks.

“It’s the dark spot near the top, about 100 feet or so up,” says Andy Stewart. “The first good branch is around 70 feet,” he adds helpfully.

“All right!” Rosenfield says. “Let’s go get the kids.” He straps on a pair of steel spurs and hefts a coil of thick rope. Hugging the tree—his arms barely reach a third of the way around it—he starts to climb, and soon falls into a labored rhythm: chunk-chunk as the spurs bite into the furrowed bark; gaze up; scout a route; feel for a grip with his fingertips; hug the trunk, chunk-chunk. Those of us pacing beneath listen to him grunt and huff. As he nears the nest, the female Cooper’s hawk dives at him with an increasing, screeching fervor: kak-kak-kak-kak-kak!

“Woah!” Rosenfield yells. “Boy, she’s mad!”

“Man, I hate watching him do this,” Stewart mutters. Most people, he says (his tone implies he means most “sane” people), would use a climbing lanyard or some other safety device should they, say, get thumped on the head by an irate Cooper’s hawk and lose their grip and fall. “But not Bob.”

At last, Rosenfield reaches the nest. “We got four chicks!” he calls down. “Two males, two females!” He rounds them up (“C’mere, you!”) and puts them in an old backpack. He uses the rope to lower the chicks to the ground. Stewart gathers up the backpack and takes the chicks to a large stump. They are about 19 days old, judging by the hint of mature feathers emerging from their down. He weighs them, measures the lengths of their various appendages and draws a little blood for DNA typing.

Meanwhile, Rosenfield stays in the canopy, gazing off into the middle distance. After the chicks have been hoisted back to the nest, I ask Stewart what Rosenfield does while he waits. “I don’t know for sure,” Stewart says. He chuckles. “I think he likes to watch the hawks fly underneath him.”

Rosenfield, a biologist at the University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point, has been free-climbing absurdly tall trees in pursuit of Cooper’s hawks for more than 30 years. Cooper’s hawks are about the size of a crow, although females are a third again as large as males, a size disparity apparent even in chicks. The sexes otherwise look alike, with a slate back, piercing red eyes and russet-streaked breast, the exact color of which varies with geography. Rosenfield has worked with other, perhaps more superficially impressive species in more superficially impressive places—gyrfalcons in Alaska, peregrine falcons in Greenland. But even though he’s most likely to study Cooper’s hawks in a city, he has a special fondness for them. “They’re addicting,” he says. “DNA really outdid itself when it figured out how to make a Cooper’s hawk.”

Not everyone thinks so. With their short, rounded wings and long tail, Cooper’s hawks are well adapted to zip and dodge through tangled branches and thick underbrush in pursuit of prey. They occasionally eat small mammals, like chipmunks or rats, but their preferred quarry is birds. Cooper’s hawks were the original chicken hawks, so called by American colonists because of their taste for unattended poultry. Now they are more likely to offend by snatching a songbird from a backyard birdfeeder, and feelings can be raw. After a local newspaper ran a story about the Victoria project, Stewart received a letter detailing the Cooper’s hawk’s many sins. “Two pages,” he says. “Front and back.”

Due in part to such antipathy, Cooper’s hawks were heavily persecuted in the past. Before 1940, some researchers estimate, as many as half of all first-year birds were shot. In the eastern United States, leg bands from hawks that had been shot were returned to wildlife managers at rates higher than those of ducks, “and it’s legal to hunt those,” Rosenfield says. Heavy pesticide use in the 1940s and ’50s likely led to eggshell thinning, which further depleted populations. On top of that, much of the birds’ forest habitat was lost to logging and development. The species’ predicament was thought so dire that, in 1974, National Geographic published an article asking, “Can the Cooper’s Hawk Survive?”

It was this worry that brought Rosenfield to Cooper’s hawks in 1980, in Wisconsin, when the state listed the species as threatened. “They had a bit of a conundrum on their hands,” Rosenfield says. Once a species is listed, the state has to put in place a plan for its recovery. “How do you call a bird recovered if you don’t know how many there are in the first place?” he says. So he went in search of them. First, he looked in places they were supposed to be: in mixed forests, or next to rivers. But he started to hear about hawks in odd places. There were reports of them nesting in towns and cities, in places like Milwaukee. If so, their habits were not in keeping with conventional raptor natural history.

As he heard from more colleagues around North America, Rosenfield expanded his study and confirmed that Cooper’s hawks are thriving in urban areas. He now works with populations in Stevens Point, as well as Albuquerque, New Mexico and Victoria, where the hawks were first detected in 1995. He goes to each place for a week or so each summer to catch adults and band chicks with local biologists. (Stewart, who himself has studied Cooper’s hawks yards for 17 years, is a retired biologist formerly with the British Columbia Ministry of the Environment.) More often than not, the people he and his colleagues visit not only invite them to conduct research on their property, but they also take an active interest in the birds’ welfare. “It’s good PR for the hawks,” Rosenfield says. “People get to see them up close, and then maybe they hate them a little less.”

In cities, Rosenfield has found, Cooper’s hawks can take advantage of a near bottomless supply of pigeons, sparrows and starlings. Unlike other species that stray into cities, Cooper’s hawks are as likely to survive there as in more natural habitats, and pairs produce similar numbers of chicks. “We’re seeing some of the highest nesting densities in cities,” Rosenfield says. Not only that, cities may be one of the best options for the long-term viability of the species. In Victoria, Cooper’s hawk populations are stable. In Milwaukee, their numbers are increasing rapidly.

In the end, Rosenfield suspects that Cooper’s hawks may not have been so rare after all. It may just be that people weren’t going to the right places. They sought them in forests and mountains, when really all they needed to do was go to their own backyards and look up.

The next day, we go back to the Douglas fir behind Joanie Wenman’s house. This time Rosenfield is going for the chick’s parents. He sets up a 12-foot-high fine-mesh “mist net,” concealing it among firs and big leaf maples. He and Stewart tether a long-suffering captive barred owl to a stand a few feet from the net—Cooper’s hawks hate barred owls—and place a speaker beneath it. In the early years, Rosenfield tells me, trapping the adult hawks was hard. “We had to do so much to hide the nets,” he says. “Because Coops have eyes like—well, you know.”

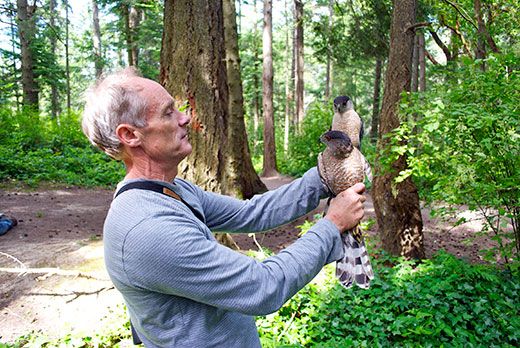

We retreat as the speaker blasts out different renditions of Cooper’s hawk distress calls. After a few minutes, we hear a series of kaks. “There she is,” Stewart whispers. We look and see the female glowering at the owl from a branch 50 feet above it. She kaks again, and then dives, steep and swift. The owl flails off its perch as the hawk sweeps over its head and slams into the net. “Got her!” Rosenfield yells. He sprints over to the hawk as she thrashes, thoroughly trussing herself, and carefully extracts her. He hands her off to Stewart, who takes her vitals as Wenman watches, asking the occasional question about the hawk’s biology.

When Stewart is finished, he gives the female to Rosenfield. “Aren’t you something,” Rosenfield says. He holds her out, appraises her, strokes her back. The female glares at him. “Hey, want to hear something cool?” he asks Wenman. He moves the female toward her head. Wenman jerks back. “Don’t worry,” Rosenfield laughs. “It’ll be fine!” Wenman does not look entirely convinced, but she makes herself stand still. Rosenfield gently brings the female toward her again, Wenman flinches—she can’t help it—but Rosenfield nods encouragingly as he presses the bird’s chest to Wenman’s ear. Wenman cocks her head, hears the hawk’s wild thudding heart. Her eyes widen at strength of the sound, and she smiles.

Eric Wagner has written about cranes in the Korean Peninsula’s demilitarized zone and penguins in Punta Tombo, Argentina.