Teaching Physics with a Massive Game of Mouse Trap

Mark Perez and his troupe of performers tour the country, using a life-sized version of the popular game to explain simple machines

![]()

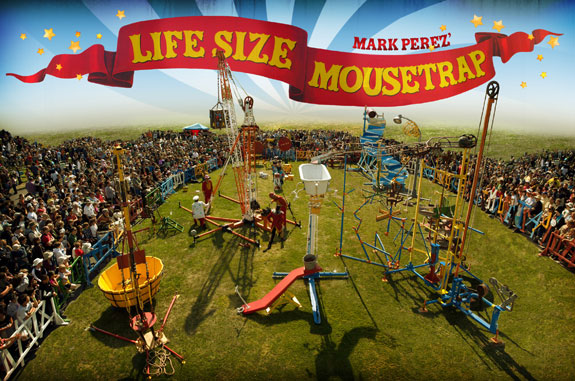

Mark Perez tours around the country with his large-scale version of the board game Mouse Trap. Courtesy of Mark Perez.

For a few consecutive years, as a kid, I put the board game Mouse Trap on my Christmas wish list. Hasbro’s commercials from the early 1990s made the game look outrageously fun. First, you build an elaborate Rube Goldberg machine, with a crane, a crooked staircase and an elevated bath tub. Then, once that is pieced together and in working condition, you use the contraption to trap your opponents’ miniature mice game pieces under a descending plastic cage.

I can hear the ad’s catchy jingle now: “Just turn the crank, and snap the plant, and boot the marble right down the chute, now watch it roll and hit the pole, and knock the ball in the rub-a-dub tub, which hits the man into the pan. The trap is set, here comes the net! Mouse trap, I guarantee, it’s the craziest trap you’ll ever see.”

Unfortunately (for me), Santa thought the game had “too many parts.” He was somehow convinced that my brother and I would misplace enough of the pieces to render the game unplayable.

Where was Mark Perez when I needed him?

Perez, a general contractor in San Francisco, believes the game of Mouse Trap is an important educational tool. He and a troupe of performers actually tour the country with a life-sized version of the board game, using its many levers, pulleys, gears, wheels, counter weights, screws and incline planes to teach audiences about Newtonian physics.

“I used to play the game a lot as a kid,” says Perez, when I catch the nomadic carnival man on the phone. “I used to put several of the games together and just kind of hack the game, not even knowing what I was doing. Then, that interest just sort of made its way into adulthood.”

In 1995, Perez began to tinker. At the outset, the self-described “maker” thought of his giant board game as a large-scale art installation. He scrapped his initial attempt a year in but returned to the project in 1998, this time renting a workspace in a reclaimed boat-building barn on San Francisco Bay. “I worked every day for eight hours and came home and worked for two to four hours more in my shop fabricating the Mouse Trap,” he says.

The crane alone took two years to construct. But by 2005, Perez had 2o sculptures, weighing a total of 25 tons, that when interconnected created a completely recognizable—and, more importantly, working—model of the popular board game.

With the “Life Size Mousetrap” complete, Perez and his motley crew of carnival-type performers took to the road, staging at times up to six shows a day at museums, science centers and festivals around the country. Prior to his construction career, Perez did some production work for bands and nightclubs in San Francisco, so he has a flair for the dramatic. He stars as the enthusiastic ringleader, and the show includes clowns, tap-dancing mice and a one-woman band (she sings and plays the drums and accordion) who sets the whole thing to music. This past summer at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, the goal of the Mouse Trap was not to catch a mouse (or a tap-dancing mouse, for that matter) but to instead drop a two-ton safe onto a car.

“I find that kids and adults both like it,” says Perez. “And when you get 400 people cheering for what you are doing, it becomes something that you want to do. I knew that I was on to something.”

At first, Perez was in it for the spectacle. Oh, and for bragging rights too. “I am the first person in the world who has done it on this scale,” he says. But, over time, he has incorporated science lessons into the act. “It sort of turned me into a physics person,” he says.

As the Rube Goldberg machine is set in motion, Perez and the other performers explain certain terms and laws of physics. For instance, when a spring that is cranked backwards is released and pulls on a cable, which then swings a hammer to hit a boot, the cast discusses potential and kinetic energy. There are also fulcrum points at play in the system. Then, when a bowling ball rolls down stairs, Perez points out that the staircase is an example of an incline plane. There are also opportune moments to talk about gravity, the workings of a screw and the mechanical advantage one can achieve by rigging several pulleys together. Esmerelda Strange, the one-woman band I mentioned earlier, has even released an album, How to Defy Gravity with 6 Simple Machines, with the rollicking explainers she sings during the show.

The show’s musician Esmerelda Strange (center) and dancing mice Rose Harden (left) and Spy Emerson (right). Courtesy of Mark Perez.

The whole endeavor is a real labor of love. The show’s cast doubles as its crew, assembling and disassembling the Mouse Trap at each site. Perez’s wife is a dancing mouse. She does all the costuming and a lot of the choreography—and drives a forklift too. Then, there are the production costs. “Just traveling with a semi-trailer costs $3 a mile. I bought a crew bus and that bus costs at least $1 a mile,” says Perez, who is working on getting funding through grants. “Then, you tack on all the extraordinary amount of insurances you need for these events. It just gets crazy.”

But the efforts and expenses are worth it, says Perez, if the Mouse Trap can provide real-life, unplugged encounters with scientific principles.

“You can go online and see all of these simple machines, but actually seeing it in person, watching a compressed coil spring release its energy to push a push rod to make a bowling ball roll down an incline plane, when you experience it and hear the clanging of the metal, it is different,” says Perez. “We make it fun.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)