Scientists Use Snails to Trace Stone Age Trade Routes in Europe

Why is a snail variety found only in Ireland and the Pyrenees? DNA analysis suggests that it hitched a boat ride with early travelers

New research shows the grove snail, which has a white-lipped variety native to only Ireland and the Pyrenees, may have hitched a ride across Europe with Stone Age humans. Image via Wikimedia Commons/Mad_Max

For nearly two centuries, biologists have been struck by a mystery of geography and biodiversity peculiar to Europe. As Edward Forbes pointed out as far back as 1846, there are a number of life forms (including the Kerry slug, a particular species of strawberry tree and the Pyrenean glass snail) that are found in two specific distant places—Ireland and the Iberian Peninsula—but few areas in between.

Recently, Adele Grindon and Angus Davidson, a pair of scientists at the University of Nottingham in the UK, decided to come at the question with one of the tools of modern biology: DNA sequencing. By closely examining the genetic diversity of one of the species shared by these two locales, the grove snail, they thought they’d be able to trace the migratory history of the creatures and better understand their present-day distribution.

When they sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of hundreds of these snails scattered across Europe, the data pointed them towards an unexpected explanation for the snails’ unusual range. As they suggest in a paper published today in PLOS ONE, the snails likely hitched a boat ride from Spain to Ireland some 8,000 years ago along with migrating bands of Stone Age humans.

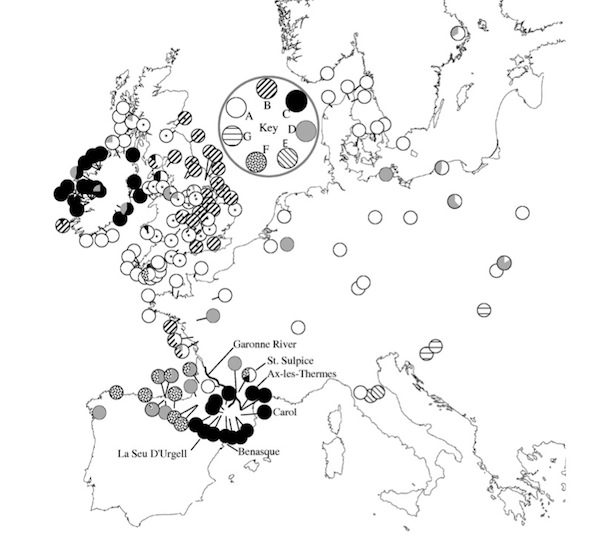

Grove snails as a whole are distributed all over Europe, but a specific variety of the snail, with a distinctive white-lipped shell, is found exclusively in Ireland and in the Pyrenees mountains that lie on the border between France and Spain. The researchers sampled a total of 423 snail specimens from 36 sites distributed across Europe, with an emphasis on gathering large numbers of the white-lipped variety.

When they sequenced genes from the mitochondrial DNA of each of these snails and used algorithms to analyze the genetic diversity between them, they found that the snails fell into one of 7 different evolutionary lineages. And as indicated by the snails’ outward appearance, a distinct lineage (the snails with the white-lipped shells) was indeed endemic to the two very specific and distant places in question:

The white-lipped ‘C’ variety of the snail, native to Ireland and the Pyrenees, demonstrated consistent genetic traits regardless of location. Image via PLOS ONE/Grindon and Davidson

Explaining this is tricky. Previously, some had speculated that the strange distributions of creatures such as the white-lipped grove snails could be explained by convergent evolution—in which two populations evolve the same trait by coincidence—but the underlying genetic similarities between the two groups rules that out. Alternately, some scientists had suggested that the white-lipped variety had simply spread over the whole continent, then been wiped out everywhere besides Ireland and the Pyrenees, but the researchers say their sampling and subsequent DNA analysis eliminate that possibility too.

“If the snails naturally colonized Ireland, you would expect to find some of the same genetic type in other areas of Europe, especially Britain. We just don’t find them,” Davidson, the lead author, said in a press statement.

Moreover, if they’d gradually spread across the continent, there would be some genetic variation within the white-lipped type, because evolution would introduce variety over the thousands of years it would have taken them to spread from the Pyrenees to Ireland. That variation doesn’t exist, at least in the genes sampled. This means that rather than the organism gradually expanding its range, large populations instead were somehow moved en mass to the other location within the space of a few dozen generations, ensuring a lack of genetic variety.

“There is a very clear pattern, which is difficult to explain except by involving humans,” Davidson said. Humans, after all, colonized Ireland roughly 9,000 years ago, and the oldest fossil evidence of grove snails in Ireland dates to roughly the same era. Additionally, there is archaeological evidence of early sea trade between the ancient peoples of Spain and Ireland via the Atlantic and even evidence that humans routinely ate these types of snails (pdf) before the advent of agriculture, as their burnt shells have been found in Stone Age trash heaps.

The simplest explanation, then? Boats. These snails may have inadvertently traveled on the floor of the small, coast-hugging skiffs these early humans used for travel, or they may have been intentionally carried to Ireland by the seafarers as a food source. “The highways of the past were rivers and the ocean–as the river that flanks the Pyrenees was an ancient trade route to the Atlantic, what we’re actually seeing might be the long lasting legacy of snails that hitched a ride…as humans travelled from the South of France to Ireland 8,000 years ago,” Davidson said.

All this analysis might help biologists solve the bigger mystery: why so many other species share this strange distribution pattern. More research could reveal that the Kerry slug, strawberry tree and others were carried from Iberia to Ireland by prehistoric humans too—and that, as a species, we were impacting the Earth’s biodiversity long before we could’ve possibly realized it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)