Saving Mali’s Migratory Elephants

A new photo library of West Africa’s desert elephants is helping researchers track the dwindling herd and protect their imperiled migration routes.

Just south of Tombouctou, where the sand dunes of the Sahara merge with a scattering of trees and shrubs, live the world's most peripatetic elephants. Mali's desert elephants migrate almost 300 miles in a year, as far as 35 miles in a day, all in pursuit of water. These elephants are "living on the edge, in the most extreme conditions," says biologist Iain Douglas-Hamilton, founder of Save the Elephants. "Their survival depends on making good decisions."

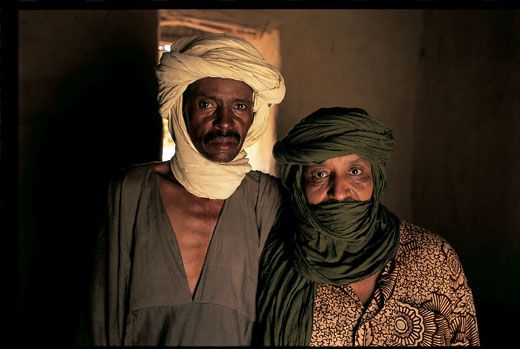

Their survival depends on human decisions too. The Tuareg nomads who share the elephants' territory "have a remarkable culture of toleration," Douglas-Hamilton says, and don't hunt the animals. As recently as 1970, several elephant populations lived in other parts of the Sahel, as the southern border of the Sahara is known. Poachers got most of them, and now only Mali's remain.

Douglas-Hamilton and other scientists and conservationists are tracking this small herd of nomadic elephants to see where and when they migrate. In 2000, researchers attached GPS collars to nine elephants; they later recovered three working units. The high-tech data (from animals dubbed Ahni, Elmehdi and Doppit Gromoppit) confirmed what some elephant-watchers had suspected for decades: the pachyderms follow a vast, counterclockwise route dotted with temporary and permanent watering holes. They linger at a lake on the northern edge of their range until the rains begin in June, then head south, eventually crossing briefly into northern Burkina Faso.

Nomadic animals are hard to protect—you can't build a fence around them and charge admission. But Vance Martin, president of The WILD Foundation, a nonprofit conservation organization, says there is "great political will in Mali to protect these animals and perhaps see them as a mobile national park." Malians have already demonstrated their affection: when a massive drought dried up the elephants' last remaining water source in 1983, the government (a constitutional democracy) trucked in water for the beasts.

The goal of ongoing tracking projects, Martin says, is to identify "choke points"—corridors the elephants must traverse to complete their migration. The WILD Foundation, Save the Elephants and other organizations are providing recommendations to the World Bank for a $9 million project to protect Mali's natural resources. By documenting where the elephants roam, not just from water hole to water hole but in search of fodder and cover, people can avoid blocking their routes with permanent settlements.

It's not easy to study Mali's elephants. They're skittish. Unlike their kin in East Africa, which all but pose for photo-snapping tourists in Land Rovers, these elephants run from the sound of an engine. They hide in thorny acacia forests during the day, when the temperature routinely reaches 120 degrees Fahrenheit, emerging to drink from water holes in the cooler privacy of the night.

With patience and lots of memory cards for their digital cameras, however, elephant researchers have amassed enough photographs of the camera-shy animals to identify about 250 individuals. Freelance photographer Carlton Ward Jr. provided 3,000 pictures to the photo identification project; team members there have captured another 2,000 useful images. Researchers think there are at least 400 elephants in the group, based on photographs, aerial surveys and studies of dung deposits (the more dung, the logic goes, the more elephants; much of a wildlife biologist's work is somewhat less than glamorous).

Elephants may look alike to you and me, but the shapes of their ear flaps and their tusks set them apart. The heat-releasing ear flaps have distinctive folds and, over an elephant's 60-year life span, they often accumulate tears.

No one is sure why these desert elephants have such stubby tusks. The animals may suffer from a dietary deficiency, although they seem healthy and are reproducing successfully. More likely, in a not-so-natural version of natural selection, poachers killed more of the animals with large, showy tusks.

Elephant identification projects in other parts of Africa have allowed researchers to observe some fairly sophisticated social interactions. Female and young elephants cluster together in groups dominated by one matriarch; males tend to be loners. The older the matriarch, according to one study, the better a leader she is. She and her followers raise more young and are more likely to bunch up to protect the young when they hear an unfamiliar call.

Researchers are beginning to decipher elephant calls. Their bellows include frequencies well below the range of human hearing and can travel through air up to six miles. Elephants appear to hear even with their feet. Their rumbles create seismic waves in the ground, and elephants have been shown to freeze and look toward the source of a seismic wave 100 feet away.

Somehow elephants communicate with one another quite clearly. Last June, the first rains of the season finally freed Mali's elephants from the overgrazed lake where they had been trapped during the hottest, driest part of the year. Carlton Ward raced to the top of a nearby dune and saw more than 100 muddy elephants trudging south, to the next stop on their route, in a single file.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)