This Rare, White Bear May Be the Key to Saving a Canadian Rainforest

The white Kermode bear of British Columbia is galvanizing First Nations people fighting to protect their homeland

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/fd/0efd4a8c-5f43-4e75-adbe-843c8f599ee2/sep2015_d01_kermodebears.jpg)

Very quietly we paddle to shore in a raft from the research vessel, which has stopped at the mouth of a small river cascading into the Pacific, one of more than a hundred salmon-bearing rivers in the 1,500-square-mile territory of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais people. We’re halfway up the coast of British Columbia, in the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest, in one of the largest unspoiled temperate rainforests on earth. We climb out and sit on boulders in the intertidal zone, in front of a meadow. Behind it is primeval forest, a solid wall of trees—western red cedar, Sitka spruce, alder, hemlock, Douglas fir.

A crow let out two clarion caws as we came in, and now every animal within earshot knows of our arrival. The humans are back. Four of us have mounted serious lenses on tripods, and we are all waiting motionlessly, respectfully. Big gobs of meringuelike foam drift down the final run of the river into the seething surf. “Organic matter,” whispers our guide, Philip Charles, a 26-year-old Brit who has a bachelor’s degree in animal conservation science and has been made an honorary Kitasoo for all the work he has done to help these First Nations people reassert sovereignty over their homeland, and to get ecotourism going.

The Kitasoo merged with the Xai’xais during the second half of the 1800s and founded the community of Klemtu, on Swindle Island, on the Inside Passage from Vancouver to Alaska. The main trade item along the coast was eulachon, an oily smelt whose flesh was a food staple and whose oil was used as a medicine and for illumination. By the end of the 20th century, though, there weren’t enough eulachon to sustain a market. Today, many of the more than 300 Kitasoo/Xai’xais living here rely on ecotourism.

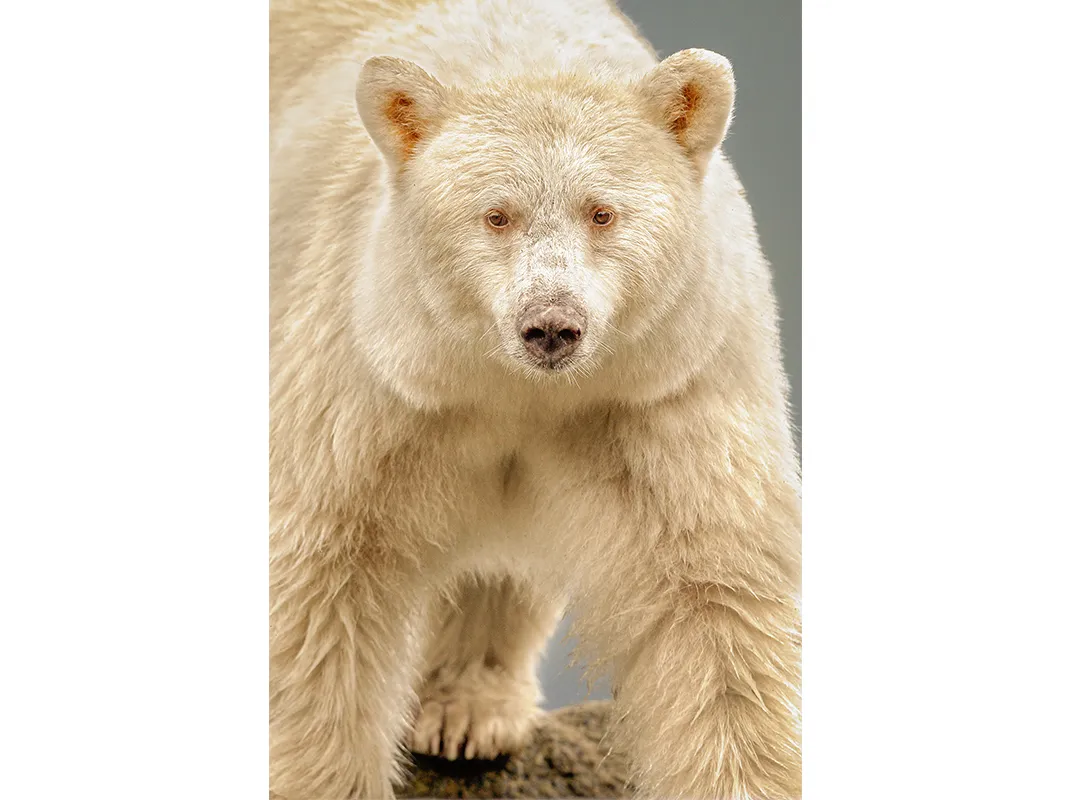

After 20 minutes, Charles points to a luminous white bear, maybe 300 pounds, which has come out of the dark forest on the other side of the river, some 200 feet upstream. She slips gently down into a pool fed by water gushing over a ledge. Within a few minutes, she bats a salmon into her mouth and ambles with it back into the forest.

The white bear is known to the Kitasoo as the Moksgm’ol, the spirit, or ghost, bear. The Kitasoo have been living on these coastal islands and fjord-diced tongues of mainland for thousands of years. They revere every living thing, but the Moksgm’ol is especially sacred. It is one of the rarest bears on earth. There are as few as 100, according to some estimates. Scientifically, the white ones, along with their closest black relatives, belong to a subspecies of black bear: the Kermode bear, Ursus americanus kermodei, named in 1905 for Francis Kermode, who helped zoologists find the bears and later became the director of the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria. Geneticists have since learned that the coloration results from a mutation in a gene involved in the production of melanin. (It’s not one of the four genes responsible for albinism.) The trait is recessive: Both parents must carry a copy of the mutated gene for their offspring to be white. In the Great Bear Rainforest, some 500 to 1,200 black bears might be carriers.

But “no one really knows how many bears there are in the Great Bear Rainforest,” cautions Chris Darimont, the Hakai-Raincoast professor of geography at the University of Victoria, who is partnering with the Kitasoo/Xai’xais and other First Nations, including the Heiltsuk, down the coast, in the first on-the-ground research incorporating indigenous knowledge and customs in the study of the rainforest’s bears.

The largest concentration of white bears, an estimated 7 out of a population of 35, inhabits 80-square-mile Gribbell Island, in the territory of the Gitga’at, the next nation up the coast. The greatest number, maybe 50 or 60, is on Princess Royal Island, adjacent to Gribbell and ten times larger. And there are frequent sightings around Terrace, on the mainland to the north. In 2014, guides at the Spirit Bear Lodge, in Klemtu, saw eight, the most since the lodge had opened six years earlier.

This bear at the river, a female that has a cub, was first spotted two and a half weeks ago. There are no other bears here, no competition, no males to kill her cub—which they sometimes do to get the female back into estrus. Charles says he has returned with guests from the lodge eight times, and only once did mother and cub not appear. Yesterday she left the cub alone with Charles and his party for ten minutes, as if she wanted the cub to learn that people are not so bad after all. They have obviously never encountered a hunter, the greatest immediate threat to bears (black and grizzlies) in the Great Bear Rainforest, where more than two dozen a year are killed by hunters authorized by British Columbia’s Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. It is illegal to hunt a white bear under any circumstance, but a hunter with a permit could take a black bear carrying the gene.

Charles says the cub is a male in its first year of life. It’s October now. Next spring, when the bears leave their den, his mother will boot him out into the world and he’ll be on his own.

**********

After a minute or so mom re-emerges from the woods without the salmon, slips back into the pool and catches another one. She sits on some rocks and tears its flesh apart and devours it.

The diet of all the bears here, and of the local wolves, is primarily salmon, berries and seaweed. The native people eat these same foods, along with deer and halibut, mussels and sea urchin. Salmon, though, is the sine qua non of this ecosystem. Bears carry the salmon into the forest, where the rotting carcasses, rich in nitrogen, fertilize the soil. The nitrogen permeates the trees and the flowering plants; even the snails and slugs get it. The sea feeds the forest, and the bears are the bearers of these nutritious infusions.

Each of the spawning rivers in the Kitasoo/Xai’xais territory has its own salmon population, born in the river and guided by the river’s unique olfactory signature; the fish return to spawn after years of wandering in the North Pacific. Each river is on its own schedule, with four of the seven Pacific species—sockeye, coho, pink and chum—running up the same river at different times. Climate change, though, is threatening these runs by warming up the waters, and thus threatening the bears that fatten up on the salmon to get through the winter. Overfishing is also a problem here.

The pink salmon that we watch the mother bear devour are already dead. Having spawned and expired upstream, they have floated down. “Yesterday she caught two live ones,” Charles tells us. “Some bears fish fast; they catch 20 salmon in 20 minutes and devour them immediately. Others are really picky and will only eat the brain and eggs. There is a huge range in the personalities of individual bears, just like us.”

Her cub comes out of the woods and joins in the feast. He has a reddish collar and his white coat is shaded brownish here and there, unlike his mother’s. We debate in whispers whether this is juvenile coloration and the cub will get whiter with age, whether his coat is an imperfect expression of the mutation, or whether it’s just dirty.

The mutation probably rose to prominence during the last ice age, hypothesizes Kermit Ritland, a population geneticist at the University of British Columbia who led the study that identified it. Glaciers then covered most of the Pacific Northwest. Perhaps a black bear population was cut off on a strip along the coast, and inbreeding increased the mutation’s frequency and its odds of meeting up with itself. Later, as the glaciers melted and the sea rose, some of the bears might have been stranded on these islands while others traveled back to the mainland.

Researchers have recently discovered that white bears attempting to capture salmon are 30 percent more successful than black bears during the daytime, presumably because, from the perspective of fish in the river, the white bears are less visible against the sky, like the white-bellied Bonaparte’s gulls and glaucous-winged gulls that are plentiful in the area. Part of this study involved researchers dressing up in white or black coveralls and entering the river to see which outfit spooked the salmon less.

So the white forms seem to have a slight edge in the quest for protein, but not enough for their mutated gene to have more than a 10 to 30 percent frequency. Why the white coloration persists in the population remains something of a puzzle, and scientists don’t yet know whether it comes with any other ecological consequences.

The mom and cub cross the river, which is only 30 feet wide, and go down into another pool behind some rocks, which the mother climbs up and peers over, now only 50 feet away. With only her head visible, she studies us intently, drinks us in and sniffs us out with her ash-colored nose, the way elephants do with their trunks. A bear’s sense of smell is ten times stronger than a dog’s, which is 1,000 times stronger than a human’s, and it is the main sense used during the day, a Kitasoo guide told me.

The mom decides not to come any closer, and she and the cub slip into the woods. I wonder what she makes of the brace of cameras clicking away, of all the attention she is getting, like a celebrity at a photo op. She is a celebrity, an official animal of British Columbia, and the panda of Canada. That’s what the spirit bear has been called by the environmental groups that enlisted it in the battle to protect the Great Bear Rainforest, which began in the 1990s and is still going on. At this point, about a third of the Great Bear Rainforest is fully protected, and not all of the First Nations have signed off on the most recent agreement proposed by a coalition of environmental groups and adopted by the provincial government.

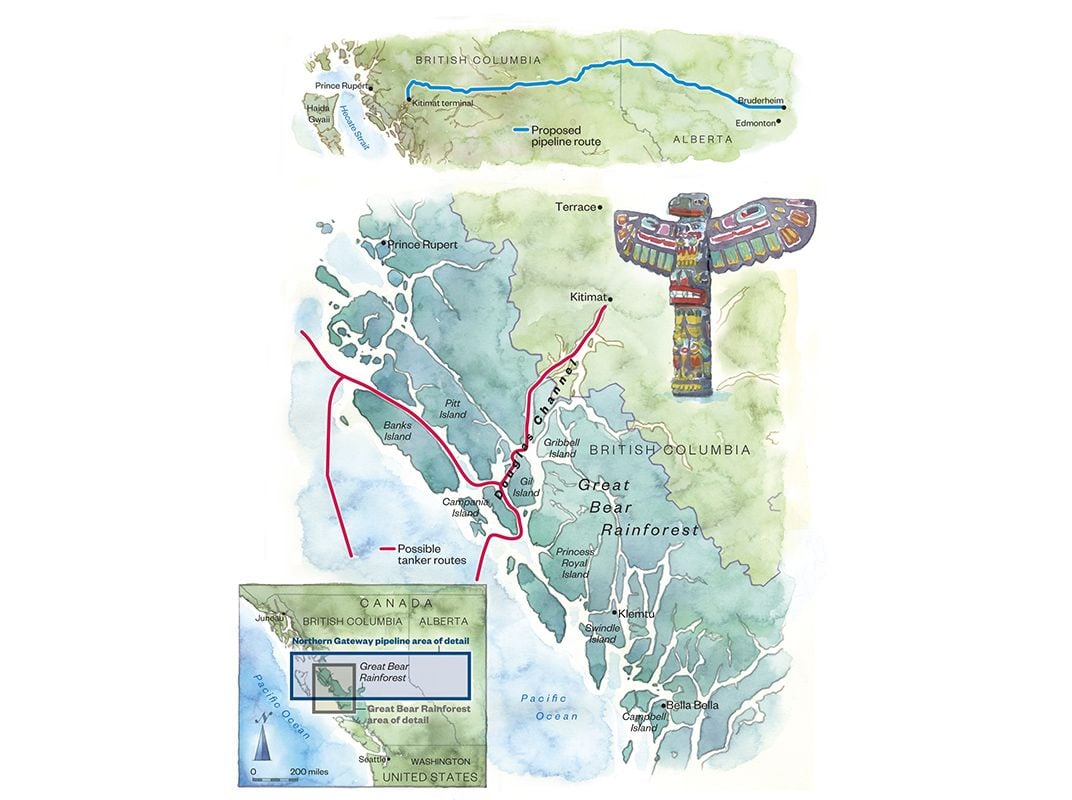

With a new threat to the ecosystem posed by the proposed Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline, which would bring crude oil extracted from the Alberta tar sands to the town of Kitimat, up the coast, the bear’s services as a charismatic animal, good for raising funds and rallying people to the cause, are required again. The Natural Resources Defense Council, for instance, has recruited the bear in its new campaign to “Save the Spirit Bear Coast” and stop the pipeline. If it were constructed, tankers would have to navigate the narrow, rocky, 100-mile-long Douglas Channel, and a spill could be catastrophic.

The Moksgm’ol is also a cash cow, for the Spirit Bear Lodge and the other tour operators that take visitors to the islands and fjords where it lives. The bear, like the white buffalo of the American plains, is traditionally seen as a giver of good luck and power to those it appears to. One showed up when the Kitasoo/Xai’xais were building a new Big House in Klemtu in 2002. This was the first one built since the early 1900s, because missionaries and governments, after arriving in the late 19th century, had banned the ceremonies, dances and other cultural practices that took place in there. The spirit bear’s arrival was seen as propitious. It hung around for a few days, and then disappeared as mysteriously as it had come.

All of us by the river agree that the patient female we have been observing is no ordinary bear, and that we too have had a brief encounter with a very special being. We all high-five.

**********

During the five and a half hours we hang out with the bears, we have plenty of time to take in the majesty of our surroundings. The crow in the alder is watching for salmon eggs washed out of nests to float down the river, as are the gulls and dippers on the river’s banks, and a juvenile eagle sits in the hemlock, his father keeping an eye on him from a nearby perch. Bobbing out in the surf are red phalaropes and, a first for me, a marbled murrelet, which, along with the also-threatened northern spotted owl, was used to combat the logging of California’s old-growth coastal forests. Out in the channel behind the research vessel, five humpback whales are spouting geysers as high as trees. They are bubble feeding, creating a net of air bubbles through which they will swim up from below with their mouths open and gobble up the disoriented krill.

Behind the forest that lines the sea, hidden from view, huge granite domes rise up to 5,000 feet. Some have waterfalls spurting down their sheer walls from higher, snow-fed lakes. Philip Charles says there are white mountain goats on the summits. In winter, when the shoreline is white with snow, the goats sometimes come down to feed on seaweed and mussels.

I have been, along with another of the bear watchers here, Melissa Groo, to many of the world’s Edens, including the bai, the clearing in the rainforest of the Central African Republic, where hundreds of forest elephants come out and carry on most of their social life. But this one is especially magical, even mystical. Not only because of the bears—and their gentle, nurturing side that we are witnessing—but because the whole ecosystem, swarming with life on land and sea, puts being alive into a perspective much different from our modern urban one. We are at one with all that surrounds us. We breathe the same air; we are all of a piece.

As my grandmother whispered to me on her deathbed, we are all transitional characters.

The Kitasoo have many stories about shape-shifting, with animals taking human form and vice versa. The greatest shape-shifter is the sea otter. Bears are regarded as particularly close to humans; if you take off the fur, bears become people. In one story, a woman is kidnapped by and marries a handsome man who is actually a bear, and they have three kids, with human faces and bear bodies. One of the kids is the color of snow because of a deal that Raven, a trickster and Creator of everything, had made with the black bears long ago. After turning himself into a child to learn how to make fire, Raven, then white, flew out through a hut’s smoke hole, singeing his wings and covering them with soot. He remained black for the rest of time, but he convinced the bears to agree that some of their cubs would be white.

In another story, told to the Canadian poet Lorna Crozier, people and animals could once talk to each other. The first bear to meet a human taught the human what plants to eat and how to catch salmon. The bear was about to teach the human all about hibernation, when another human came along and killed it with an arrow. This is why, the Kitasoo say, people have to collect food and firewood to make it through the winter, instead of sleeping through its cold, dark months.

**********

In 2007 the provincial and federal governments, along with nongovernmental organizations, raised $120 million for a trust made available to the 27 nations in the Great Bear Rainforest, to use for the stewardship of the land and the well-being of the people. The Kitasoo/Xai’xais opted to use some of the money for ecotourism, and opened the Spirit Bear Lodge in 2008. Its success depends not only on the spirit bear, but also on the coastal black bears and the grizzlies, which also attract tourists and keep the ecosystem healthy. Doug Neasloss, 33, a member of the Raven (crest) clan, was a guide for Spirit Bear Lodge until he became chief councilor of Klemtu, a position he held until 2013. His first summer as a guide, he was returning to the lodge after viewing grizzlies with some clients when he passed a boat full of men who didn’t look like tourists. “I didn’t have a good feeling, and the next day I returned to where we watched the bears, and there was one that had been decapitated, skinned and its paws cut off.” Trophy hunters. There are also poachers only interested in selling bear livers to the lucrative Chinese market.

Neasloss’ concern about the bears brought him into contact with Chris Darimont, who was studying coastal wolves and occasionally came upon the remains of bears that had been killed by hunters. Darimont was the science director of an NGO called Raincoast Conservation Foundation, which raised $1.3 million to buy the hunting concession to an area in the Kitasoo/Xai’xais territory and beyond that was particularly thick with grizzlies. By owning the license, Raincoast prevents hunters from being able to shoot the bears there. In 2012, nine nations belonging to what is called the Great Bear Initiative voted to ban all bear hunting in their traditional territories, but the provincial government is still issuing licenses there. Darimont and Neasloss realized that the first step in protecting both grizzlies and black bears, including the white ones, was to collect baseline data about their numbers, movements, relatedness and behavior. William Housty, one of the Heiltsuk’s progressive young leaders, had reached the same conclusion. Housty, who has a degree in natural resource management, knew about a passive hair snag that others had used with success in the interior. It consists of a square of barbed wire maybe eight feet long on each side and a foot and a half off the ground, with a stack of sticks and moss in the middle that reek of fish. Suspended eight feet above, there’s an aluminum pie plate containing a cloth soaked with vanilla, loganberry or orange anise extract or beaver anal mucus, scents that any bear in the vicinity will pick up from miles away. As the bear steps over the barbed wire, some of its arm, belly or leg hair is caught in some of the tines, which it doesn’t even notice. And when the bear comes by the trap, night or day, infrared video cameras fixed to nearby trees start recording. Last spring traps were set at the mouths of 70 of Kitasoo/Xai’xais’ salmon-bearing rivers.

I spend a day with Neasloss and 28-year-old Krista Duncan, who collects the hair and video footage from the traps and rebaits them. The material is sent to a lab at the University of Victoria, where the DNA is extracted, along with other information, and matched up with the video. This noninvasive method of data-gathering, as opposed to darting and radio-collaring, is in keeping with the deep respect the coastal people have for the bears.

“We scientists are just beginning to catch up with the wealth of traditional and local ecological knowledge on the rainforest coast, which is what makes this collaboration so exciting,” Darimont says.

What the hair-trap data are showing so far is that the grizzlies are on the move, probably looking for rivers with more salmon, Neasloss and Darimont think. Some grizzlies are swimming out to the islands where the white bears are. When a grizzly appears on a river where black bears are feeding on salmon, the island bears, white ones included, bolt into the forest. The white and black bears probably won’t leave the islands entirely, Darimont says, but “they might eat less salmon, which is not great. Or they might switch to increased nocturnal foraging.”

We visit a bear trap that has been set up on the edge of a lake created by an artificial dam. Gold miners lived here until the 1940s, when the mine was shut down. In 2003 a logging company moved in, clear-cutting the slopes and loading the logs on ships, and then leaving everything behind, apparently in great haste: trailers, 20 fuel barrels still full, a pickup truck with the key in the ignition, a big rusting Caterpillar, even a daily logbook, which Neasloss finds in one of the trailers and takes. He is hopping mad about this toxic mess.

Near the trailers, in a patch of Labrador tea, is the hair trap, with two balls of fresh white fur on adjacent tines. A new white bear. There was no sign of it when Duncan checked the trap two weeks earlier. This is the sixth white bear whose hair she has found this year. She puts on blue plastic gloves and removes the hair with tweezers and puts it into a small yellow envelope and Ziploc bag. Then she burns the tines with a small blowtorch so no hair residue will mix with the next samples.

The next trap has been flooded by high tide and has black bear hair. It is on the edge of a forest of ancient red cedars, some thousand years old, Neasloss tells me. They have old man’s beard moss hanging from their lower branches, an epiphytic licorice fern that is thousands of times sweeter than sugar. He cuts me a slice of its stem to bite into and shows me a western yew tree, one of the hardest trees in the forest, from which bows and arrows were made.

The root system of one of the cedars has been hollowed out into a den, in which Neasloss finds black bear hair. One of the tree’s buttresses has been chopped long ago by what he recognizes was a nephrite ax, the green jade axes that the coastal people used until 1846, when they adopted steel axes. The nephrite came from two locations in what is now Washington State and was traded up and down the coast. Someone probably chopped out enough of the tree’s buttress to make a mask.

We visit Jess Housty, William Housty’s 28-year-old sister, in Bella Bella, the capital of the Heiltsuk nation, on Campbell Island, southeast of Klemtu. She too is involved in the struggle to regain indigenous British Columbians’ sovereignty over their own territories and is a powerful speaker. She has described the coast as vital “on a deeply intimate and personal level because it’s the place where my ancestors’ bones are buried. It’s the place that’s in my veins, that’s imprinted in my DNA....There’s no other geography in the world where I make sense.”

She is working with Neasloss on fighting the Northern Gateway pipeline. Her strategy is to get the coastal nations’ customary marine territory—not only their land but also the sections of sea they have fished for centuries—recognized as such, which would give them control over who could come in and out. They could then stop the nonnative fishermen who are taking so many salmon out of the rivers, and prevent the tankers from using Douglas Channel.

She tells me that the Heiltsuk, like the Kitasoo, believe there is no distinction between the land and the water. “Every land animal has a supernatural sea counterpart. There are sea bears who are the counterparts of the grizzlies and black bears and spirit bears.” And the land bears around here spend most of their waking time in the water and get most of their protein from it, so they’re semi-aquatic themselves, I suggest.

Two weeks after my visit, a Russian tanker full of oil, diesel fuel and a mix of other hydrocarbons loses power and goes adrift off the rocky coast of Haida Gwaii, the archipelago west of the Great Bear Rainforest. An American tugboat that happens to be in the port of Prince Rupert, on the Alaska border, gets to the tanker before it is dashed to pieces. Darimont emails that he is hugely relieved, but part of him wishes it had come closer to being a real disaster. The provincial government needs to realize the folly of letting tankers go up and down the Douglas Channel, he says. The Canadian government, eager to sell its tar sands bitumen to China, has green-lighted the Northern Gateway pipeline, but there is a lot of opposition to it in British Columbia, and at least 14 nations on its route from Alberta to Kitimat have vowed to fight it every step of the way.

Darimont thinks the pipeline, whether it happens or not, is a blessing in disguise, because it has united nations in the Great Bear Rainforest that at times didn’t get along. With threats from hunting, climate change, overfishing and the movement of the grizzlies looming, the spirit bear and the mysterious ecocosmos that is its home need all the defenders they can get.

**********

After the tide went out, mother and child emerged from the forest again and ate kelp and scraped acorn barnacles off the rocks. There is a Kitasoo expression: When the tide is out, the table is set. At one point, the two of them came within ten feet of us, and acted as if we didn’t exist. We sat frozen in elation, in a collective rapture, flooded with love for the bear and her cub and for each other, even though some of us, bear and human, were meeting for the first—and last—time.

Related Reads

Great Bear Wild

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Shoumatoff.jpg)