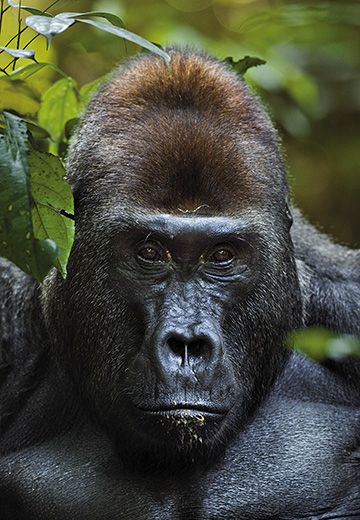

Rare and Intimate Photos of a Gorilla Family in the Wild

Two photographers ventured deep into the forests of central Africa to capture touching photos of a 33-year-old wild silverback and his clan

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Primal-Instinct-silverback-Makumba-631.jpg)

Butterfly season came suddenly to the Dzanga-Sangha reserve, a dense rainforest in the Central African Republic. Furious storms of butterflies filled the air, and their frail brown forms carpeted the earth. They swarmed over Fiona Rogers and Anup Shah and also seemed to pester the gorilla family that the photographers were following. The harassed apes bashed away at the insects and clamped their mouths shut so none would fly in.

Except, that is, for the family’s dominant female, Malui. She plowed straight through one drove of butterflies resting in the bais, as the swampy meadows in the forest are known. Seeming to relish the rush of wings, she paused to let the butterflies envelop her. Then she did it again.

“She was almost dancing with them,” Rogers remembers.

Having studied Malui for nearly a month, the photographers were ready when they saw a mischievous look on her face. Their portrait of the frolicking gorilla is part of an extraordinary portfolio, the first of its kind to come out of Dzanga-Sangha’s gorilla habituation program, which is in itself remarkable: Only four wild western lowland gorilla families in the world tolerate human observers.

The western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) is a separate species from the mountain gorillas of Dian Fossey fame. Western lowland gorillas have shorter fur than their mountain cousins and often sport distinctive red patches on their foreheads. The silverbacks, which can stand six feet tall and weigh over 400 pounds, are more spectacularly silver, with gray hair from their necks to their ankles. The lowland gorillas lick termites from tree trunks and climb for football-size fruit, while mountain gorillas eat a lot of bamboo and wild celery; they inhabit ancient volcanoes and other lofty spots in East Africa, mostly in Rwanda and Uganda. The western lowland gorillas live on the other side of the continent, in the lush lowland rainforest of the western Congo basin.“There are all sorts of places in Africa where you think there should be gorillas but there aren’t any,” says James Deutsch, who runs the Wildlife Conservation Society’s programs in Africa.“They are kind of a fragile species. Their distribution is very spotty.”

There are more western lowland gorillas by far: an estimated 200,000, compared with just 770 mountain gorillas. (Almost all zoo gorillas are lowland gorillas.) Even so, the higher-altitude apes are much more extensively studied, partly because East Africa has had a longer tradition of field research and conservation. The mountain gorillas are also much better suited for habituation, the systematic process in which wild animals are carefully tracked by human observers until we are no longer threatening or even interesting to them. Then tourists can visit, and researchers and photographers can work.

The habituation of some primates, like bush babies or nocturnal lemurs, can be accomplished in a day, while mountain gorillas take about a year. Habituation of western lowland gorillas spans many years and frequently fails altogether. Living at low densities in vast forests, the lowland gorillas are shy, and their large home ranges give them plenty of places to hide. To untrained observers, they can be almost impossible to spot in the thick vegetation.

But the Dzanga-Sangha trackers are BaAka Pygmies who notice every knuckle print, bent stem and absent leaf. “They can tell from the way that water gathers on the leaf litter that a gorilla walked there,” says Angelique Todd, the researcher who led the habituation effort, which is run by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in collaboration with the Central African Republic’s government. Some of the trackers are former gorilla poachers. Sooner or later, they always find the gorilla’s nests.

Malui’s family of nine has been followed from dawn to dusk nearly every day since 2000. The head of the clan is Makumba, a gruff and imposing silverback with an endearing bald spot in his gray fur. His name means “with speed” in the local language. For two years he and his family sprinted through the forest to escape their pursuers, sometimes eluding them for weeks.

After that, Makumba became merely aggressive for about a year, charging at and otherwise menacing the trackers. These days he, his two females (both of whom remained hostile even longer than the silverback) and their offspring mostly ignore observers. “It’s not exactly trust,” Todd says. “It’s more tolerance. He knows we won’t do him any harm.”

For the most part the gorillas are sedate creatures. The youngsters tussle. Huge Makumba sometimes tends to the little ones. The family travels often in search of food and listens for the rustle of elephants and leopards. “My impression was that gorillas were a bit more brawn than brain,” Rogers says. “But you can see that they are so thoughtful and conscious of each other. There’s a serenity about them.”

There’s also a fierceness. Makumba may veer toward violence if a strange silverback approaches. He still occasionally charges human visitors, and he once bit an overly intrusive tracker, all the way through the man’s bicep to the bone.

“The mountain gorilla experience doesn’t compare with this one,” says Shah, who has photographed both groups. “Watching mountain gorillas is almost like watching black cows in a green field. These guys are wild.”

Makumba is about 33, quite old for a dominant wild gorilla, and it seems his days as a family leader are numbered. Two of his four original females left over the years, and habituated males have trouble attracting new mates, which is one controversial aspect of the habituation program. Other concerns include the spread of disease between gorillas and humans, heightened gorilla stress levels and the increased vulnerability to poaching that comes with being taught not to fear people. But the habituated animals have given scientists a window into their social structure, feeding habits and movements in the forest.

They are also ambassadors for their species. The Dzanga-Sangha gorillas receive 500 visitors a year, most of them tourists; an hour of observation costs about $400. (The money pays trackers and other staff.) Their forest is not a destination for the faint of heart. The drive from the capital city of Bangui takes 12 to 24 hours. “I’ve never done it with less than two flat tires,” says Chris Whittier, a veterinarian in the wildlife health sciences department of the National Zoo, who has treated the habituated animals. And the hike to find the animals can be grueling.

Many of the western lowland gorillas are in even more isolated areas. In 2006 and 2007, Wildlife Conservation Society workers canoeing the swamp forests of the northern Congo Republic counted tens of thousands of previously unknown animals clustered on little islands of dry land.

The remote habitat of western lowland gorillas likely helps protect them, although they are listed as critically endangered. They are threatened by increased rainforest logging, being killed for bushmeat and Ebola outbreaks.

Whittier is working with colleagues on strategies to vaccinate and otherwise protect the Dzanga-Sangha animals against a number of diseases, including Ebola and respiratory infections, and recently darted Makumba’s family to test the technique.

Aiming his air pistol at Makumba’s expansive back, he was admittedly apprehensive. But Makumba just “pulled the dart out, threw it on the ground and gave us a dirty look,” Whittier says. Then the gorilla went about his business.