Raising Alexandria

More than 2,000 years after Alexander the Great founded Alexandria, archaeologists are discovering its fabled remains

Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from its original form and updated to include new information for Smithsonian’s Mysteries of the Ancient World bookazine published in Fall 2009.

There’s no sign of the grand marbled metropolis founded by Alexander the Great on the busy streets of this congested Egyptian city of five million, where honking cars spouting exhaust whiz by shabby concrete buildings. But climb down a rickety ladder a few blocks from Alexandria’s harbor, and the legendary city suddenly looms into view.

Down here, standing on wooden planks stretching across a vast underground chamber, the French archaeologist Jean-Yves Empereur points out Corinthian capitals, Egyptian lotus-shaped columns and solid Roman bases holding up elegant stone arches. He picks his way across the planks in this ancient cistern, which is three stories deep and so elaborately constructed that it seems more like a cathedral than a water supply system. The cistern was built more than a thousand years ago with pieces of already-ancient temples and churches. Beneath him, one French and one Egyptian worker are examining the stonework with flashlights. Water drips, echoing. “We supposed old Alexandria was destroyed,” Empereur says, his voice bouncing off the damp smooth walls, “only to realize that when you walk on the sidewalks, it is just below your feet.”

With all its lost grandeur, Alexandria has long held poets and writers in thrall, from E. M. Forster, author of a 1922 guide to the city’s vanished charms, to the British novelist Lawrence Durrell, whose Alexandria Quartet, published in the late 1950s, is a bittersweet paean to the haunted city. But archaeologists have tended to give Alexandria the cold shoulder, preferring the more accessible temples of Greece and the rich tombs along the Nile. “There is nothing to hope for at Alexandria,” the English excavator D. G. Hogarth cautioned after a fruitless dig in the 1890s. “You classical archaeologists, who have found so much in Greece or in Asia Minor, forget this city.”

Hogarth was spectacularly wrong. Empereur and other scientists are now uncovering astonishing artifacts and rediscovering the architectural sublimity, economic muscle and intellectual dominance of an urban center that ranked second only to ancient Rome. What may be the world’s oldest surviving university complex has come to light, along with one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Pharos, the 440-foot-high lighthouse that guided ships safely into the Great Harbour for nearly two millennia. And researchers in wet suits probing the harbor floor are mapping the old quays and the fabled royal quarter, including, just possibly, the palace of that most beguiling of all Alexandrians, Cleopatra. The discoveries are transforming vague legends about Alexandria into proof of its profound influence on the ancient world.

“I’m not interested in mysteries, but in evidence,” Empereur says later in his comfortable study lined with 19th-century prints. Wearing a yellow ascot and tweed jacket, he seems a literary figure from Forster’s day. But his Center for Alexandrian Studies, located in a drab modern high-rise, bustles with graduate students clacking on computers and diligently cataloging artifacts in the small laboratory.

Empereur first visited Alexandria more than 30 years ago while teaching linguistics in Cairo. “It was a sleepy town then,” he recalls. “Sugar and meat were rationed, it was a war economy; there was no money for building.” Only when the city’s fortunes revived in the early 1990s and Alexandria began sprouting new office and apartment buildings did archaeologists realize how much of the ancient city lay undiscovered below 19th-century constructions. By then Empereur was an archaeologist with long experience digging in Greece; he watched in horror as developers hauled away old columns and potsherds and dumped them in nearby Lake Mariout. “I realized we were in a new period—a time to rescue what we could.”

The forgotten cisterns of Alexandria were in particular danger of being filled in by new construction. During ancient times, a canal from the Nile diverted floodwater from the great river to fill a network of hundreds, if not thousands, of underground chambers, which were expanded, rebuilt and renovated. Most were built after the fourth century, and their engineers made liberal use of the magnificent stone columns and blocks from aboveground ruins.

Few cities in the ancient or medieval world could boast of such a sophisticated water system. “Underneath the streets and houses, the whole city is hollow,” reported Flemish traveler Guillebert de Lannoy in 1422. The granite-and-marble Alexandria that the poets thought long gone still survives, and Empereur hopes to open a visitors center for one of the cisterns to show something of Alexandria’s former glory.

The Alexandria of Alexandrias

At the order of the brash general who conquered half of Asia, Alexandria—like Athena out of Zeus’ head—leapt nearly full grown into existence. On an April day in 331 B.C., on his way to an oracle in the Egyptian desert before he set off to subdue Persia, Alexander envisioned a metropolis linking Greece and Egypt. Avoiding the treacherous mouth of the Nile, with its shifting currents and unstable shoreline, he chose a site 20 miles west of the great river, on a narrow spit of land between the sea and a lake. He paced out the city limits of his vision: ten miles of walls and a grid pattern of streets, some as wide as 100 feet. The canal dug to the Nile provided both fresh water and transport to Egypt’s rich interior, with its endless supply of grain, fruit, stone and skilled laborers. For nearly a millennium, Alexandria was the Mediterranean’s bustling center of trade.

But less than a decade after he founded it, Alexander’s namesake became his tomb. Following Alexander’s death in Babylon in 323 B.C., his canny general Ptolemy—who had been granted control of Egypt—stole the dead conqueror’s body before it reached Macedonia, Alexander’s birthplace. Ptolemy built a lavish structure around the corpse, thereby ensuring his own legitimacy and creating one of the world’s first major tourist attractions.

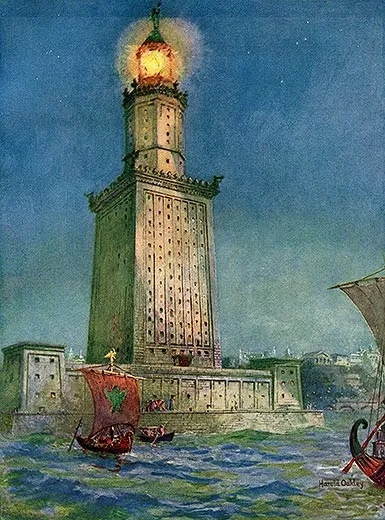

Ptolemy, already rich from his Asian conquests and now controlling Egypt’s vast wealth, embarked on one of the most astonishing building sprees in history. The Pharos, soaring more than 40 stories above the harbor and lit at night (no one knows exactly how), served the purpose of guiding ships to safety, but it also told arriving merchants and politicians that this was a place to be reckoned with. The city’s wealth and power were underscored by the temples, wide colonnaded streets, public baths, massive gymnasium and, of course, Alexander’s tomb.

Though schooled in war, Ptolemy proved to be a great patron of intellectual life. He founded the Mouseion, a research institute with lecture halls, laboratories and guest rooms for visiting scholars. Archimedes and Euclid worked on mathematics and physics problems here, and it was also here that the astronomer Aristarchus of Samos determined that the sun was the center of the solar system.

Ptolemy’s son added Alexandria’s famous library to the Mouseion complex. The first chief of the library, Eratosthenes, measured the earth’s circumference to an accuracy within a few hundred miles. The library contained an unparalleled collection of scrolls thanks to a government edict mandating that foreign ships hand over scrolls for copying.

And the ships arrived from all directions. Some sailing on the monsoon winds imported silks and spices from the western coast of India via the Red Sea; the valuable cargo was then taken overland to the Mediterranean for transport to Alexandria. One ship alone in the third century B.C. carried 60 cases of aromatic plants, 100 tons of elephant tusks and 135 tons of ebony in a single voyage. Theaters, bordellos, villas and warehouses sprang up. Ptolemy granted Jews their own neighborhood, near the royal quarter, while Greeks, Phoenicians, Nabateans, Arabs and Nubians rubbed shoulders on the quays and in the marketplaces.

The go-go era of the Ptolemies ended with the death, in 30 B.C., of the last Ptolemy ruler, Cleopatra. Like her ancestors, she ruled Egypt from the royal quarter fronting the harbor. Rome turned Egypt into a colony after her death, and Alexandria became its funnel for grain. Violence between pagans and Christians, and among the many Christian sects, scarred the city in the early Christian period.

When Arab conquerors arrived in the seventh century A.D., they built a new capital at Cairo. But Alexandria’s commercial and intellectual life continued until medieval times. The Arab traveler Ibn Battuta rhapsodized in 1326 that “Alexandria is a jewel of manifest brilliance, and a virgin decked out with glittering ornaments” where “every wonder is displayed for all eyes to see, and there all rare things arrive.” Soon after, however, the canal from Alexandria to the Nile filled in, and the battered Pharos tumbled into the sea.

By the time Napoleon landed at Alexandria as a first stop on his ill-fated campaign to subdue Egypt, in 1798, only a few ancient monuments and columns were still standing. Two decades later, Egypt’s brutal and progressive new ruler—Mohammad Ali—chose Alexandria as his link to the expanding West. European-style squares were laid out, the port grew, the canal reopened.

For more than a century, Alexandria boomed as a trade center, and it served as Egypt’s capital whenever the Cairo court fled the summer heat. Greek, Jewish and Syrian communities existed alongside European enclaves. The British—Egypt’s new colonial rulers—as well as the French and Italians built fashionable mansions and frequented the cafés on the trendy corniche along the harbor. Though Egyptians succeeded in throwing off colonial rule, independence would prove to be Alexandria’s undoing. When President Nasser—himself an Alexandrian—rose to power in the 1950s, the government turned its back on a city that seemed almost foreign. The international community fled, and Alexandria slipped once again into obscurity.

The First Skyscraper

The rediscovery of ancient Alexandria began 14 years ago, when Empereur went for a swim. He had joined an Egyptian documentary film crew that wanted to work underwater near the 15th-century fort of Qait Bey, now a museum and tourist site. The Egyptian Navy had raised a massive statue from the area in the 1960s, and Empereur and the film crew thought the waters would be worth exploring. Most scholars believed that the Pharos had stood nearby, and that some of the huge stone blocks that make up the fortress may have come from its ruins.

No one knows exactly what the Pharos looked like. Literary references and sketches from ancient times describe a structure that rose from a vast rectangular base—itself a virtual skyscraper—topped by a smaller octagonal section, then a cylindrical section, culminating in a huge statue, probably of Poseidon or Zeus. Scholars say the Pharos, completed about 283 B.C., dwarfed all other human structures of its era. It survived an astonishing 17 centuries before collapsing in the mid-1300s.

It was a calm spring day when Empereur and cinematographer Asma el-Bakri, carrying a bulky 35-millimeter camera, slipped beneath the waters near the fort, which had been seldom explored because the military had put the area off limits. Empereur was stunned as he swam amid hundreds of building stones and shapes that looked like statues and columns. The sight, he recalls, made him dizzy.

But after coming out of the water, he and el-Bakri watched in horror as a barge crane lowered 20-ton concrete blocks into the waters just off Qait Bey to reinforce the breakwater near where they had been filming. El-Bakri pestered government officials until they agreed to halt the work, but not before some 3,600 tons of concrete had been unloaded, crushing many artifacts. Thanks to el-Bakri’s intervention, Empereur—who had experience examining Greek shipwrecks in the Aegean Sea—found himself back in diving gear, conducting a detailed survey of thousands of relics.

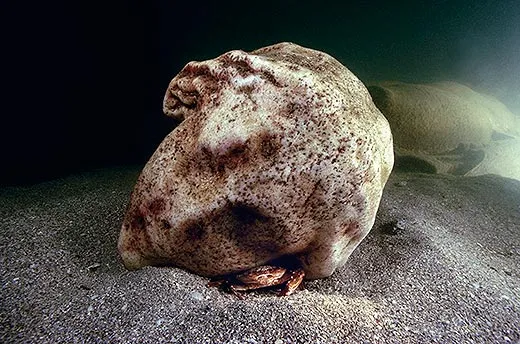

One column had a diameter of 7.5 feet. Corinthian capitals, obelisks and huge stone sphinxes littered the seafloor. Curiously, half a dozen columns carved in the Egyptian style had markings dating back to Ramses II, nearly a millennium before Alexandria was founded. The Greek rulers who built Alexandria had taken ancient Egyptian monuments from along the Nile to provide gravitas for their nouveau riche city. Empereur and his team also found a colossal statue, obviously of a pharaoh, similar to one the Egyptian Navy had raised in 1961. He believes the pair represent Ptolemy I and his wife, Berenice I, presiding over a nominally Greek city. With their bases, the statues would have stood 40 feet tall.

Over the years, Empereur and his co-workers have photographed, mapped and cataloged more than 3,300 surviving pieces on the seafloor, including many columns, 30 sphinxes and five obelisks. He estimates that another 2,000 objects still need cataloging. Most will remain safely underwater, Egyptian officials say.

Underwater Palaces

Franck Goddio is an urbane diver who travels the world examining shipwrecks, from a French slave ship to a Spanish galleon. He and Empereur are rivals—there are rumors of legal disputes between them and neither man will discuss the other—and in the early 1990s Goddio began to work on the other side of Alexandria’s harbor, opposite the fortress. He discovered columns, statues, sphinxes and ceramics associated with the Ptolemies’ royal quarter—possibly even the palace of Cleopatra herself. In 2008, Goddio and his team located the remains of a monumental structure, 328 feet long and 230 feet wide, as well as a finger from a bronze statue that Goddio estimates would have stood 13 feet tall.

Perhaps most significant, he has found that much of ancient Alexandria sank beneath the waves and remains remarkably intact. Using sophisticated sonar instruments and global positioning equipment, and working with scuba divers, Goddio has discerned the outline of the old port’s shoreline. The new maps reveal foundations of wharves, storehouses and temples as well as the royal palaces that formed the core of the city, now buried under Alexandrian sand. Radiocarbon dating of wooden planks and other excavated material shows evidence of human activity from the fourth century B.C. to the fourth century A.D. At a recent meeting of scholars at Oxford University, the detailed topographical map Goddio projected of the harbor floor drew gasps. “A ghost from the past is being brought back to life,” he proclaimed.

But how had the city sunk? Working with Goddio, geologist Jean-Daniel Stanley of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History examined dozens of drilled cores of sediment from the harbor depths. He determined that the edge of the ancient city had slid into the sea over the course of centuries because of a deadly combination of earthquakes, a tsunami and slow subsidence.

On August 21, in A.D. 365, the sea suddenly drained out of the harbor, ships keeled over, fish flopped in the sand. Townspeople wandered into the weirdly emptied space. Then, a massive tsunami surged into the city, flinging water and ships over the tops of Alexandria’s houses, according to a contemporaneous description by Ammianus Marcellinus based on eyewitness accounts. That disaster, which may have killed 50,000 people in Alexandria alone, ushered in a two-century period of seismic activity and rising sea levels that radically altered the Egyptian coastline.

Ongoing investigation of sediment cores, conducted by Stanley and his colleagues, has shed new light on the chronology of human settlement here. “We’re finding,” he says, “that at some point, back to 3,000 years ago, there is no question that this area was occupied.”

The Lecture Circuit

Early Christians threatened Alexandria’s scholarly culture; they viewed pagan philosophers and learning with suspicion, if not enmity. Shortly after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, in A.D. 380, theological schools sprang up around the Mediterranean to counter pagan influence. Christian mobs played some part in the destruction of the Library of Alexandria; the exact causes and dates of assaults on the library are still hotly disputed. And in A.D. 415, Christian monks kidnapped and tortured to death the female philosopher and mathematician Hypatia, long considered the last of the great pagan intellects. Most historians assumed that Alexandria’s learned glow dimmed as the new religion gained power.

Yet now there is evidence that intellectual life in Alexandria not only continued after Hypatia’s death but flourished more than a century later, apparently for Christian and pagan scholars alike. Less than a mile from the sunken remnants of the royal quarters, in the middle of Alexandria’s busy, modern downtown, Polish excavators have uncovered 20 lecture halls dating to the late fifth or sixth century A.D.—the first physical remains of a major center of learning in antiquity. This is not the site of the Mouseion but a later institution unknown until now.

One warm November day, Grzegorz Majcherek, of Warsaw University, directs a power shovel that is expanding an earthen ramp into a pit. A stocky man in sunglasses, he is probing the only major piece of undeveloped land within the ancient city’s walls. Its survival is the product of happenstance. Napoleon’s troops built a fort here in 1798, which was enlarged by the British and used by Egyptian forces until the late 1950s. During the past dozen years, Majcherek has been uncovering Roman villas, complete with colorful mosaics, which offer the first glimpses into everyday, private life in ancient Alexandria.

As the shovel bites into the crumbly soil, showering the air with fine dust, Majcherek points out a row of rectangular halls. Each has a separate entrance into the street and horseshoe-shaped stone bleachers. The neat rows of rooms lie on a portico between the Greek theater and the Roman baths. Majcherek estimates that the halls, which he and his team have excavated in the past few years, were built about A.D. 500. “We believe they were used for higher education—and the level of education was very high,” he says. Texts in other archives show that professors were paid with public money and were forbidden to teach on their own except on their day off. And they also show that the Christian administration tolerated pagan philosophers—at least once Christianity was clearly dominant. “A century had passed since Hypatia, and we’re in a new era,” Majcherek explains, pausing to redirect the excavators in rudimentary Arabic. “The hegemony of the church is now uncontested.”

What astonishes many historians is the complex’s institutional nature. “In all the periods before,” says New York University’s Raffaella Cribiore, “teachers used whatever place they could”—their own homes, those of wealthy patrons, city halls or rooms at the public baths. But the complex in Alexandria provides the first glimpse of what would become the modern university, a place set aside solely for learning. Though similarly impressive structures may have existed in that era in Antioch, Constantinople, Beirut or Rome, they were destroyed or have yet to be discovered.

The complex may have played a role in keeping the Alexandrian tradition of learning alive. Majcherek speculates that the lecture halls drew refugees from the Athens Academy, which closed in A.D. 529, and other pagan institutions that lost their sponsors as Christianity gained adherents and patrons.

Arab forces under the new banner of Islam took control of the city a century later, and there is evidence that the halls were used after the takeover. But within a few decades, a brain drain began. Money and power shifted to the east. Welcomed in Damascus and Baghdad by the ruling caliphs, many Alexandrian scholars moved to cities where new prosperity and a reverence for the classics kept Greek learning alive. That scholarly flame, so bright for a millennium in Alexandria, burned in the East until medieval Europe began to draw on the knowledge of the ancients.

The Future of the Past?

The recent spate of finds would no doubt embarrass Hogarth, who at the end of the 19th century dug close to the lecture-hall site—just not deep enough. But mysteries remain. The site of Alexander’s tomb—knowledge of which appears to have vanished in the late Roman period—is still a matter of speculation, as is the great library’s exact location. Even so, ancient Alexandria’s remains are perhaps being destroyed faster than they’re being discovered, because of real estate development. Since 1997, Empereur has undertaken 12 “rescue digs,” in which archaeologists are given a limited period of time to salvage what they can before the bulldozers move in for new construction. There is not enough time and money to do more, Empereur says; “It’s a pity.” He echoes what the Greek poet Constantine Cafavy wrote nearly a century ago: “Say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.”

Passing a new gaudy high-rise, Empereur cannot conceal his disdain. He says that the developer, fearful that striking archaeological treasures would delay construction, used his political connections to avoid salvage excavations. “That place had not been built on since antiquity. It may have been the site of one of the world’s largest gymnasiums.” Such a building would have been not just a sports complex but also a meeting place for intellectual pursuits.

For two years, Empereur examined an extensive necropolis, or burial ground, until the ancient catacombs were demolished to make way for a thoroughfare. What a shame, he says, that the ruins were not preserved, if only as a tourist attraction, with admission fees supporting the research work.

Like archaeologists of old, today’s visitors to Egypt typically ignore Alexandria in favor of the pyramids of Giza and the temples of Luxor. But Empereur is seeking funding for his cistern museum, while the head of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities envisions a series of transparent underwater tunnels in Alexandria’s harbor to show off the sunken city. The dusty Greco-Roman Museum is getting a much-needed overhaul, and a museum to display early mosaics is in the works. A sparkling new library and spruced-up parks give parts of the city a prosperous air.

Yet even on a sunny day along the curving seaside corniche, there is a melancholy atmosphere. Through wars, earthquakes, a tsunami, depressions and revolutions, Alexandria remakes itself but can’t quite shake its past. Cafavy imagined ancient music echoing down Alexandria’s streets and wrote: “This city will always pursue you.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/andrew2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/andrew2.png)