Poison Hath Been This Italian Mummy’s Untimely End

A lethal helping of foxglove seems to have triggered the downfall of a warlord of Verona

:focal(919x320:920x321)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/14/95145211-0989-4fe4-ba0b-bcd190476c0a/3_some_steps_of_the_exploration.jpg)

Italian warlord Cangrande I della Scala was at his peak when he marched into the city of Treviso as conqueror and ruler of a newly unified northern Italy in 1329. Four days later, he died at the ripe old age of 38.

Chronicles of the day suggested that he had made the mistake of drinking from a polluted spring and fell violently ill. But the sudden circumstances of his death also inspired rumors of more nefarious forces at play. Now, analysis of Cangrande’s mummy backs up the theory that he was the victim of foxglove poisoning. While it’s impossible to know for sure if Cangrande was murdered, the researchers examining his remains certainly suspect foul play.

Cangrande was the most famous member of the Scaligeri dynasty, which ruled Verona, Italy, for 90 years. He took the throne of Verona in 1311 at just 20 years old. Cangrande gained a reputation as a warrior and a political leader, waging a campaign to gain control of Italy’s northern cities that culminated in the win at Treviso. Intrigue, military conflict and betrayal marked his rise to power. Cangrande was also a leading patron of the poet Dante Alighieri, of Inferno fame.

Historical chroniclers are divided on the circumstances of the warlord's death. The late 14th-century historian Galeazzo Gatari speculated that someone had poisoned Cangrande, and 15th-century scholar Torello Saraina went so far as to claim that a poisoned fruit had been the murder weapon. But Florentine scholar Giovanni Villani attributes Congrande’s death to overeating after the battle for Treviso. And though some modern scholars dismiss the polluted spring story, Cangrande’s symptoms—nausea, diarrhea and fever—sound a lot like a case of dysentery.

In 1923 archaeologists explored the warlord’s tomb and discovered that, due to the dry environment inside, his corpse had naturally mummified. Decades later, the city of Verona and the Castelvecchio Museum approached Gino Fornaciari, a forensic pathologist at the University of Pisa, to see if modern scientific methods could provide new clues in this cold case.

Cangrande’s mummy was exhumed in 2004, and Fornaciari's team got to work. Performing a modern autopsy on a 500-year-old mummy is a bit tricky. “It is very different, because the mummy is totally dry, without blood and fluids,” explains Fornaciari. His team took CT scans and x-rays of the mummy’s abdomen and torso. Cutting a hole in the abdomen, they took tissue samples from the mummy’s intestines and liver, and even found preserved fecal matter in his bowels.

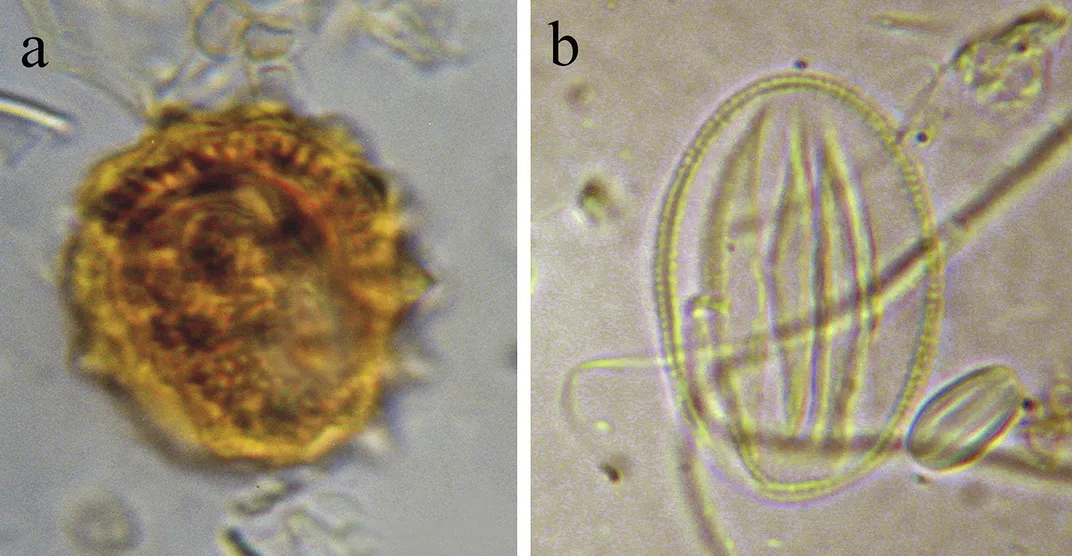

Initial analysis showed that those fecal samples contained pollen grains from a Digitalis plant, commonly known as foxglove. Further screening of the liver and stool samples revealed toxic concentrations of digitoxin and digoxin, two chemical compounds produced by Digitalis plants. Given that these compounds would have degraded over time, it’s safe to say that Cangrande had lethal levels in his system when he died, the team reported in December in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

While doctors today commonly prescribe safe dosages of digoxin and digitoxin as heart stimulants, scientists didn’t discern the heart-related healing properties of foxglove plants until the 18th century. But there is another possibility for medical use gone awry. Some healers in Cangrande’s time might have used the plant to treat snakebites, and chamomile and black mulberry, which were used for minor ailments, were also found in the mummy's tissues and feces. In addition, an account from 14th-century jurist and historian Guglielmo Cortusi says that one of Cangrande’s physicians was hanged at the gallows soon after the warlord's death. Was he being punished for administering the wrong dose of medicine?

That’s unlikely, Fornaciari and his colleagues argue. Healers at the time would have used Digitalis in ointments, not potions, and pollen in the poop suggests that the flowers and leaves of the plant must have been ingested. The symptoms match up, too—foxglove poisoning causes vomiting and diarrhea that can last for one to three days. Prior to the Renaissance, references to Digitalis as a poison are few and far between, so the new paper may represent the first hard evidence of Digitalis actually killing someone during this period.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/f2/56f241e0-9262-4260-a14f-73e7758d414b/9108969119_b5ed2fcf19_k.jpg)

“I think that their argument is sound, and I also find it plausible that the administration was accidental,” says Niels Lynnerup, a forensic pathologist at the University of Copenhagen who performed a similar study to see if famed German astronomer Tycho Brahe was a victim of mercury poisoning.

If it truly was murder, the big question is who could have committed the dirty deed. Cangrande left plenty of potential suspects behind, but Fornaciari’s money is on suspects from the Venetian Republic or the Duchy of Milan. “Cangrande became too powerful and dangerous for both,” he says.

Unfortunately, Cangrande and whoever might have killed him likely took that truth to the grave.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)