The History and Future of the Once-Revolutionary Taxidermy Diorama

In their heyday, these dead animal displays were virtual reality machines

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/2f/a62f3ba3-7e2d-4346-874c-e09eb10dd748/bg6xm4_1.jpg)

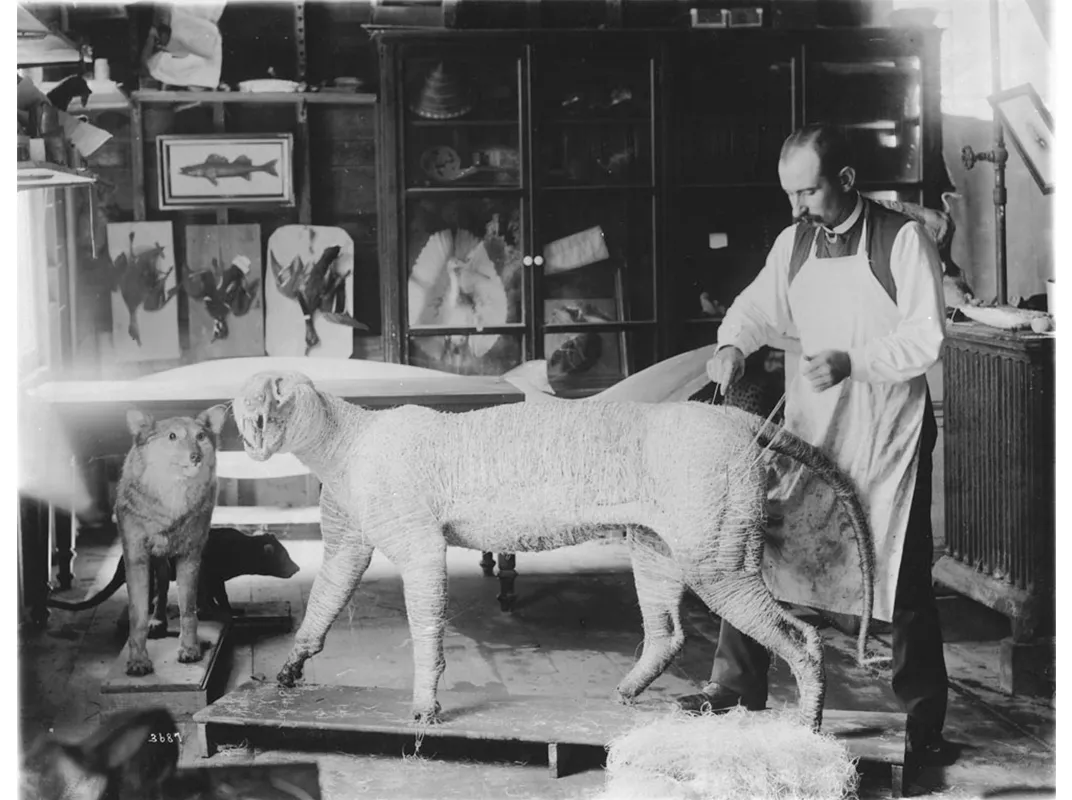

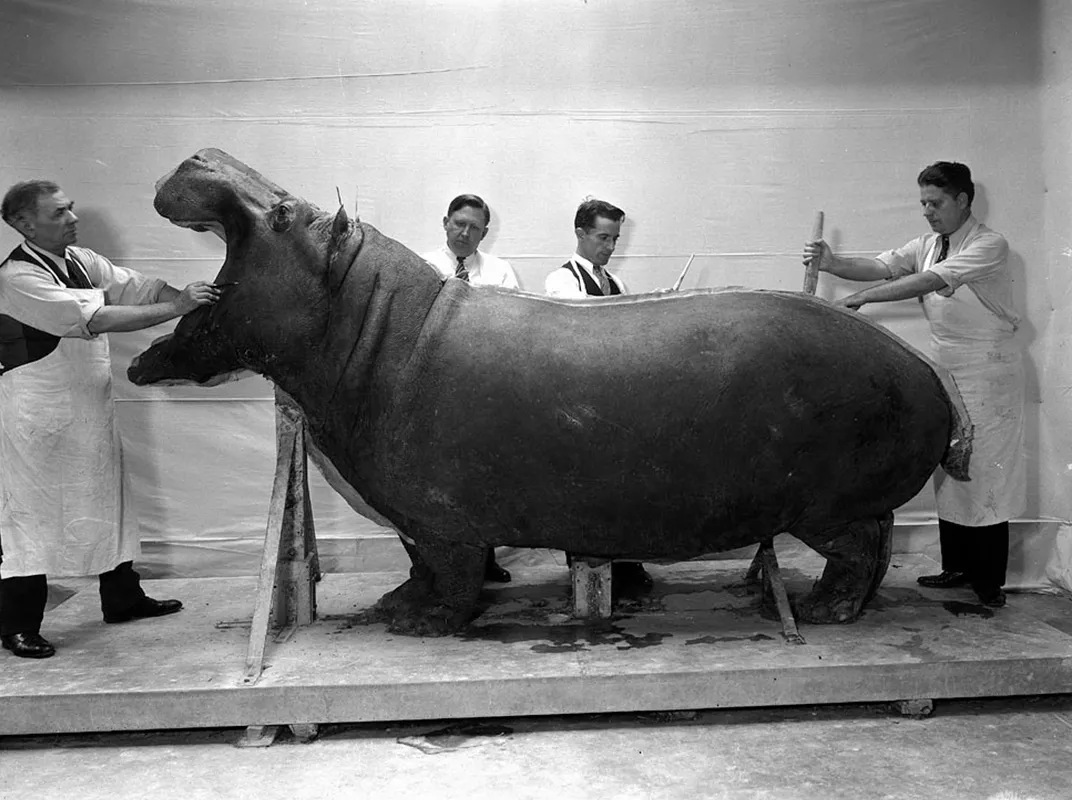

Let’s face it: taxidermy dioramas are so last century.

While some might think of these dead animal displays as a charming throwback, others consider them a dated anachronism—a blast from the past more spooky than scientific. “Super creepy,” is how a recent Washington Post Express headline recently described them. “Old and dusty,” is what comes to mind for many visitors when they picture the dimly-lit diorama halls of traditional natural history museums, says Lawrence Heaney, curator and head of the mammals division at Chicago’s Field Museum.

Today the classic taxidermy display—a vignette composed of stuffed and lifelike animals against a naturalistic habitat diorama—faces an uncertain future. At the University of Minnesota, the Bell Museum of Natural History is planning to move all of its exhibits to the university’s St. Paul campus by summer 2018. But not all of the museum’s taxidermied dioramas—which, according to the museum’s website, number “among the best examples of museum displays”—will be are coming with them. Some will be dismantled; others thrown out. “Not all the dioramas are going to go,” says Don Luce, curator of exhibits.

In 2003, the National Museum of Natural History made the controversial move to scrap its diorama displays and declined to replace its last full-time taxidermist when he retired (the museum now employs freelance taxidermists when needed, and some of its original dinosaur dioramas remain in storage). The museum substituted the old displays with specimens showcased in a more modern, scientific manner, meant to emphasize their "shared ancestry and evolution," according to Kara Blond, the museum’s assistant director for exhibitions.

Heaney, who grew up in Washington and volunteered at the Smithsonian museum when he was 14, says the switch was warranted. “Their dioramas were not particularly good,” he says. “No one would have argued that they were the finest work.”

As natural history museums around the world seek to revamp their reputations, many are reconsidering these types of dated displays altogether. Now, some are considering whether technology is the way to go. David Skelly, who directs Yale University’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, says his museum is looking into the possibility of having visitors don an Oculus Rift-style headset and experience animals’ habitats via three-dimensional digital displays. (This approach would also help address pressing worries about pests and degradation that come with closed diorama exhibits.)

To be fair, any pronouncement of the death of the taxidermy exhibit would be premature. The profession of taxidermy is experiencing something of a modern resurgence among the young and female, as Matt Blitz reported last year for Smithsonian.com. But as many question whether the diorama form has outlived its function, it’s worth asking the question: What made this idea so special in the first place?

Pam Henson, director of the Smithsonian’s institutional history division, sees taxidermy displays as part of a broader historical arc of how museum culture changed around the turn of the 19th century. At the time, museums catered mainly to upper class visitors, who didn’t need wall labels because guides explained everything to them. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, a shift to more inclusive museums saw the emergence of the self-tour. Taxidermy displays, which gave viewers more information through their relatively realistic habitats and scientific captions, marked a key step of that democratization.

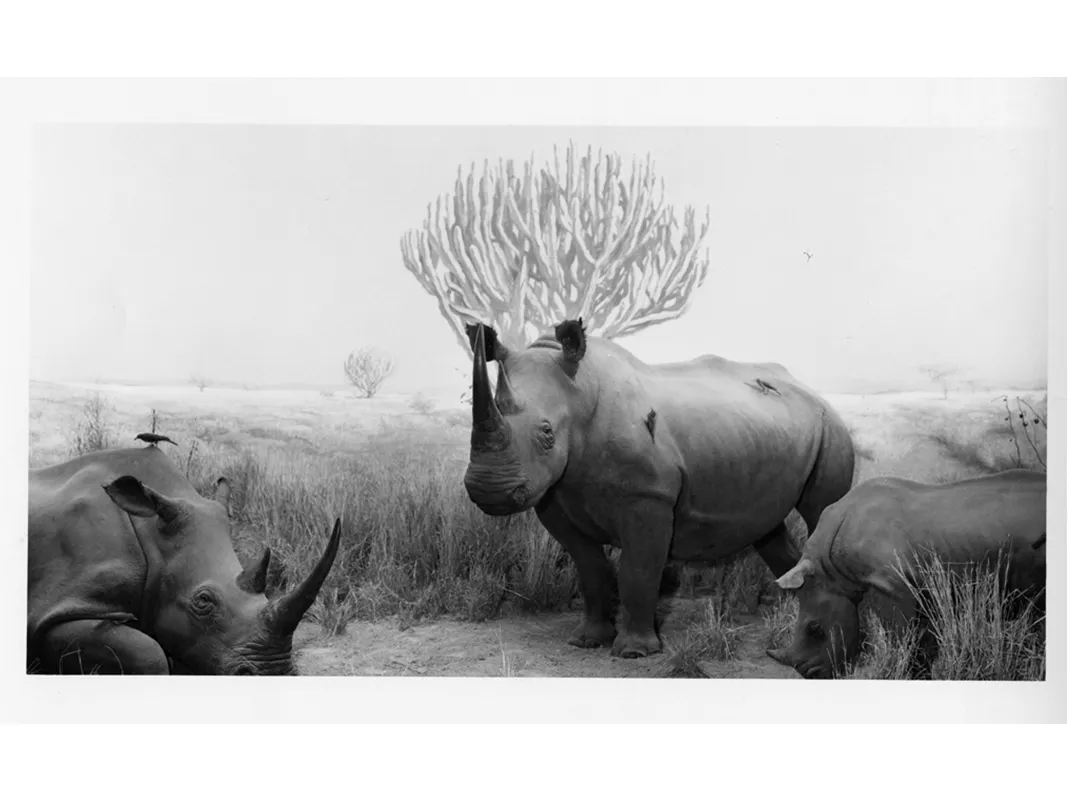

These displays took visitors to worlds they could otherwise never visit. “They were the virtual reality machines of their age, the pre-television era,” says Skelly. Dioramas sought to drop viewers, who likely had limited travel experiences, into the African savannah or the mountains of western North America. “It gave them a sense of what wildlife looked like there, and what the world was like in the places where they’d never been and likely would never go,” Skelly says.

These exhibits had a loftier purpose as well: to foster an emotional, intimate and even “theatrical” encounter with nature, says Eric Dorfman, director of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Dorfman compares taxidermy displays to the German composer Richard Wagner’s vision for the first modern opera houses. Wagner wanted the opera houses to be so dark that audience members couldn’t see those sitting in front of them, leaving individuals to grapple alone with the music.

“The same exact kind of theater is used in European gothic cathedrals, with the vaulted ceilings and the story of Christ coming through the lit, stained glass. That’s a very powerful image even to someone who is from a different religion, or an atheist,” Dorfman says. “If you imagine a hall of dioramas, frequently they’re very dark. They’re lit from inside. They create a powerful relationship between you and that image.”

While today’s viewers may not feel the same kind of intimate relationship with a taxidermied animal that Dorfman describes, they may still be getting an experience that’s hard to replicate. In a computer-mediated era, seeing a once-living animal up close offers something that digital displays can’t. “There is this duality, of the suspension of disbelief,” Dorfman says. “You’re seeing an animal in its habitat, but you’re also realizing that animal died.”

Many displays are carefully wrought in exquisite detail, right down to each starry constellation and miniature tree frog. Some of the background paintings are even considered artistic masterpieces themselves. The dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, for instance, are so renowned that the museum spent $2.5 million updating and restoring them for posterity in 2011. “These dioramas represent perhaps a kind of apotheosis of art and science in terms of craftsmanship,” Michael J. Novacek, the museum’s provost, told the New York Times.

Even as it has moved away from traditional dioramas, the National Museum of Natural History remains mindful of that history. "We are adapting and reinterpreting the traditional diorama display style in each exhibition we mount," says Blond, pointing out that some of the taxidermied animals in the mammal hall are still presented in stylized habitats. "Traditional dioramas were born in an era that emphasized understanding and celebrating individual cultures or life as part of a very specific setting or habitat. As priorities and values of society and globe have changed ... the museum has adapted accordingly."

Some curators argue that the diorama is still crucial for function of transporting viewers to places they couldn’t otherwise visit. It’s just that, today, the reasons these places are beyond most people’s reach are different: for instance, global conflict or deteriorating environments.

At the Field Museum, staff recently raised funds through a successful crowdsourcing campaign to create a new diorama for its striped hyenas collected in Somalia in 1896. Today, Somalia’s landscape has been “hammered” by conflict, making parts unsafe to visit, notes Heaney. “People want to know how those things have changed and what’s happening to these animals as a result,” he says. “We can’t go back to Somalia and get more hyenas. And we certainly can’t go back to 1896. These are things that are literally irreplaceable.”

Luce, of the Bell Museum of Natural History, points out that taxidermy dioramas are still important for getting children invested in nature—perhaps even more so today, when they tend to spend less time outside. “Heck, these kids are growing up and seeing everything on a screen,” Luce says. “Dioramas are a place where we can elicit that kind of search and observation experience.” He adds that, in the Bell Museum’s new building, dioramas will be accompanied—but not overpowered—by digital displays.

Despite their antiquity, Luce says the dioramas at the Bell Museum are worth the effort. “They’re a time capsule of that location and time,” he says. “You could say, ‘Why preserve the Mona Lisa? We could digitize that thing and see it better than you ever could going to the museum. Why waste my time going to Paris to see it?’” That the animals are real, he adds, makes them even more important to protect.

“They have given their life to science and education, and we should respect that,” he says. “We shouldn’t just toss them out.”

Editor's note, October 18, 2016: This article has been updated to reflect that the Field Museum raised funds for its new hyena diorama through a crowdfunding campaign.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)