Explore Haunting Relics of Death With New Photography Book

Placenta-wiping fetuses are only the tip of the frightberg

Morbid Curiosities, a new photography book by Paul Gambino, is not for the faint of the heart. As I was flipping through it on the subway, people physically switched seats to avoid catching a glimpse of a photograph of a preserved fetus positioned so that it was wiping its eyes with its own placenta (see above) over my shoulder. But placenta-wiping fetuses are only the tip of the frightberg.

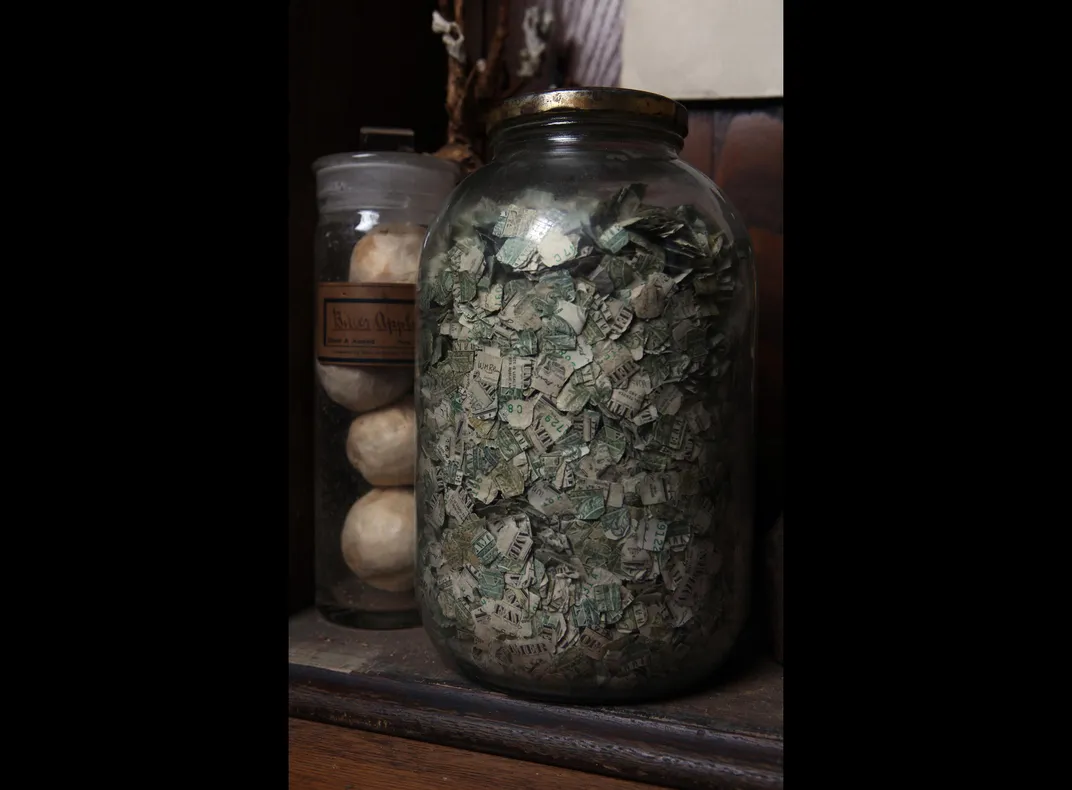

While not every image in the book is immediately horrifying, the stories behind them are guaranteed to make your skin crawl. One page, for instance, features a jar full of dollar bills, each delicately torn into dime-sized squares. The caption reads: “Jar of Insanity.” In fact, these carefully-torn dollars are the product of an extreme case of obsessive compulsive disorder. The jar was recovered from a mental hospital, Gambino explains.

“It's the physical manifestation of mental illness in a jar,” says Gambino, whose book delves into the macabre oddities of 17 different collectors from North America and beyond.

Gambino is himself a collector who has long sought out photos of death. His own collection is primarily made up of Victorian age portraits of people post mortem—mostly children, due to the high child mortality rates of that era. He began collecting these souvenirs in his late teens, after discovering a photograph of a family of ten all standing somberly in front of their cabin. The family was huddled around what was likely the matriarch, propped up lifelessly in a casket.

The author's morbid collection—and fascination—only grew from there. At some point along his journey, part of his collection was inadvertently tossed in the trash. His reaction encapsulates the relationship many collectors seem to have with their objects. “That was disastrous,” he says, recalling the incident. “You feel like you are safeguarding these pieces, like you are entrusted to care for them,” he explains, “And the thought of them being in the garbage, it kind of haunts me—no pun intended.”

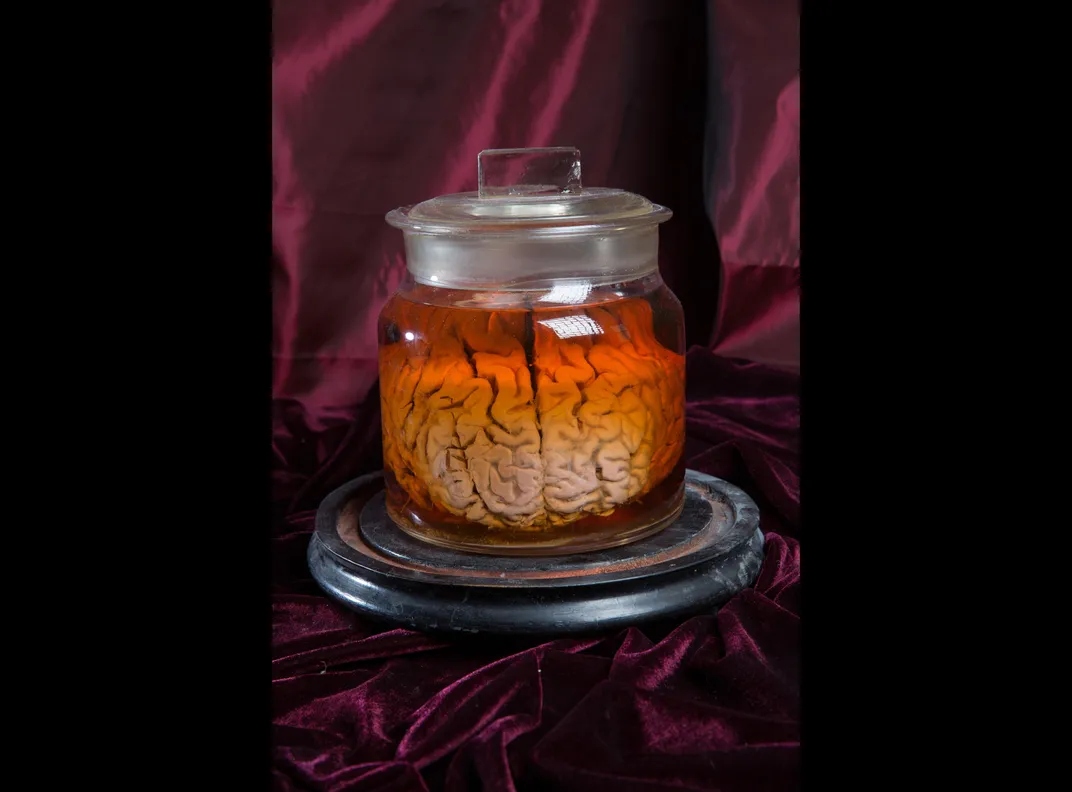

Why collect reminders of our mortality? Perhaps counterintuitively, Gambino has found, the answer is often as a way to control death: to reify it, name it, hold it in the palm of your hand. For him, surrounding himself with the very thing that petrifies him provides some form of comfort. With this richly strange, profoundly unnerving book, he shares that cold “comfort” with you. We chatted with Gambino to learn more about the collectors and fantastical objects that fill his pages.

It took you many years to complete this book. Why?

It took seven years before a publisher would actually pick up the book. All the publishers said: This is just too creepy. Once the current publisher finally picked it up, it only took about 12 months to photograph everything.

You mentioned in the book some commonalities you’ve noticed among collectors of morbid oddities. Can you elaborate?

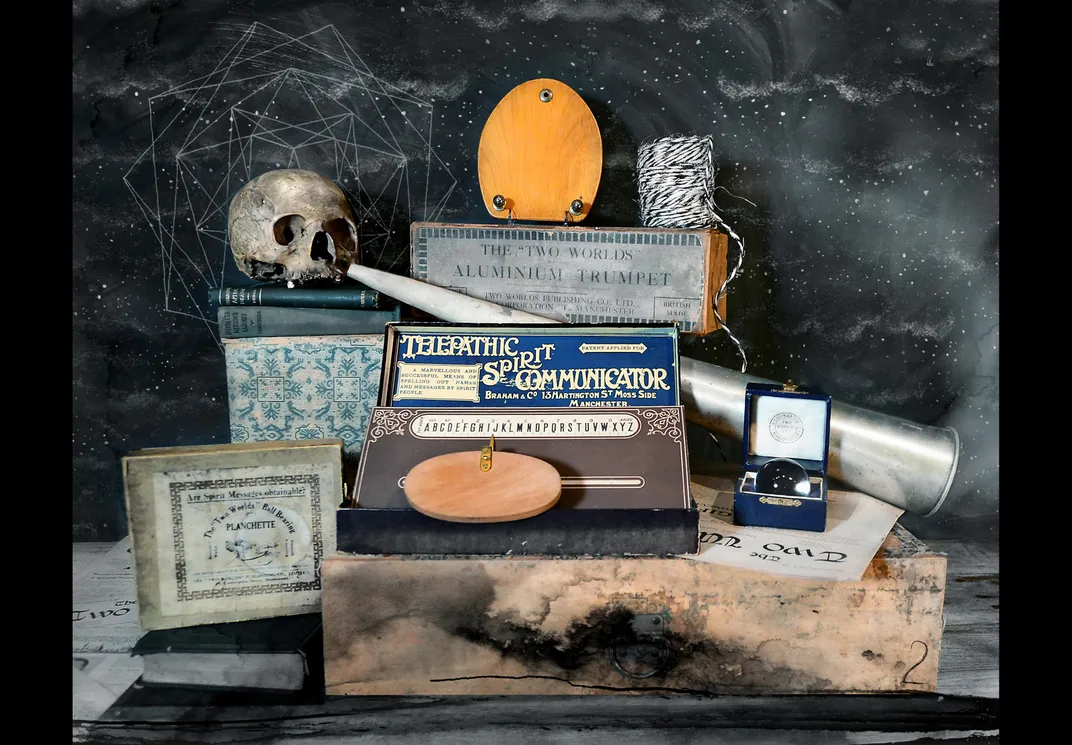

A lot of these collections are people just trying to figure out the world. If you look at the collections, it's a mixture between science, religion and magic.

Certain people surround themselves with death and feel very comfortable with death. And then there are some—like me—who are petrified by it and surround themselves with it as a reminder that it's inevitable and that you're not the only one who will go through it.

There are so many different reasons for people to collect the macabre, but the common thread is that the people feel that they are preserving bits of history; they're presenting historical pieces; they're giving a safe home to a lot of pieces that people normally would not want to have around.

How did you select the 17 collectors you included in the book?

Some of them I knew personally from my own collecting, and word spread when I started the project. At first, a lot of the collectors that I didn't know personally were wary about me coming in and photographing their collections. They were worried that I was going to portray them as kooks, or really dark people.

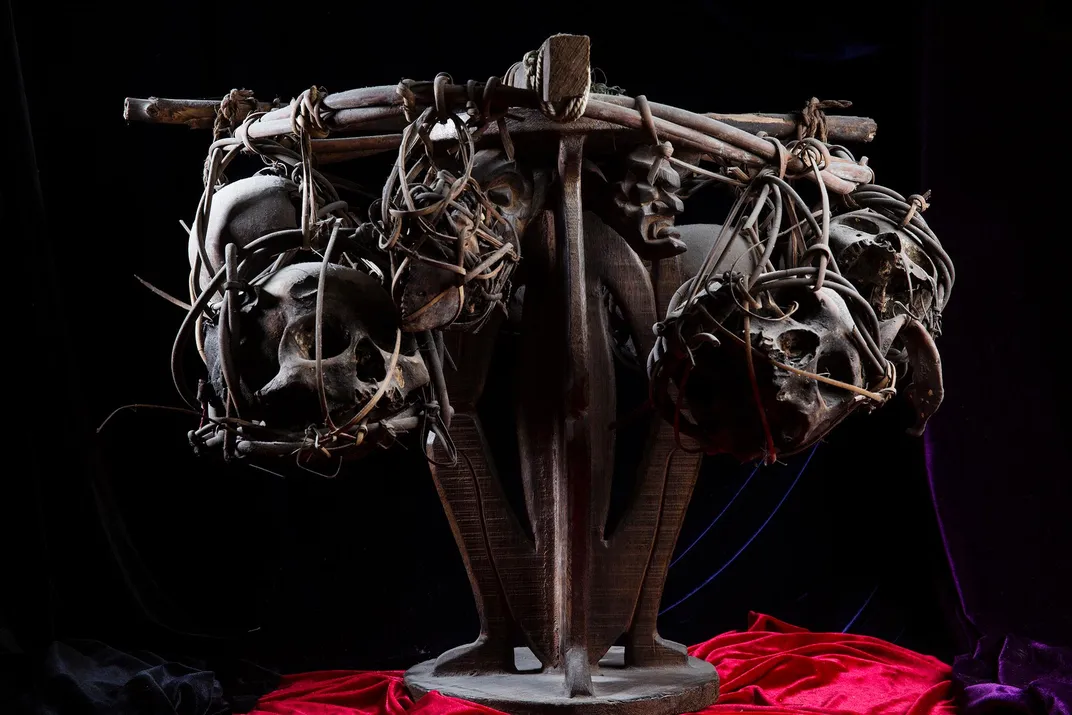

I also tried to include a variety of different collectors with broad interests. I didn't want it to look like a catalogue, like a person that has 100 skulls. Then as you're paging through and there's another skull and another skull—it really loses any kind of effect.

Most chapters begin with a portrait of the collector, but two collectors—Jessica, who collects serial killer artifacts, and Sky, whose collection centers around death—didn’t want their likenesses included in the book. Why not?

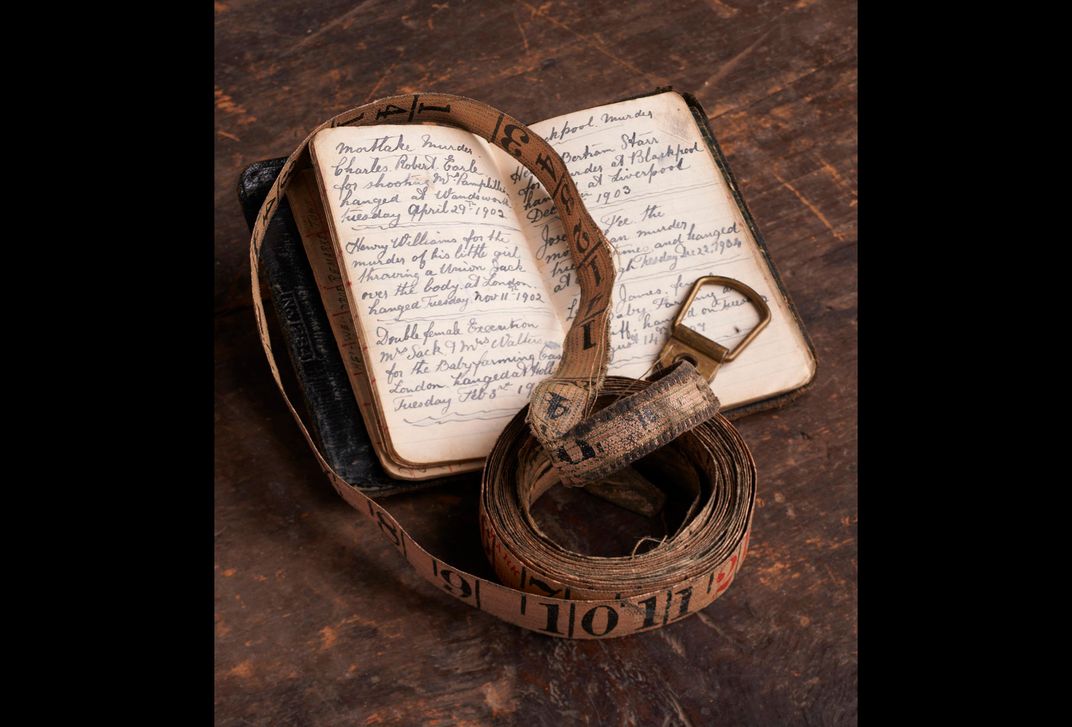

Collectors of the macabre are often labeled with inaccurate and unkind characterizations like lunatic, maniac or devil worshiper. They both wanted to keep their identities anonymous for that exact reason. I particularly understand Jessica's aversion. As soon as you get associated with serial killer artifacts, people immediately think, ‘this person is off the wall.’ Some of them, like Jessica, collect such objects because they cannot be further from that type of person. It's not that they feel some kind of empathy or sympathy for them, it's just that they can't fathom that someone could be so evil. It becomes a fascination.

You’ve said you love the idea that history make people see a seemingly innocuous object in a completely different and often darker way—like the insanity jar. What are some other objects that spoke to you?

When researching the book I steered away from collectors that just collect for the sake of things being exploitive and gruesome. Knowing the history behind the piece changes it entirely. Because now it’s a piece of history.

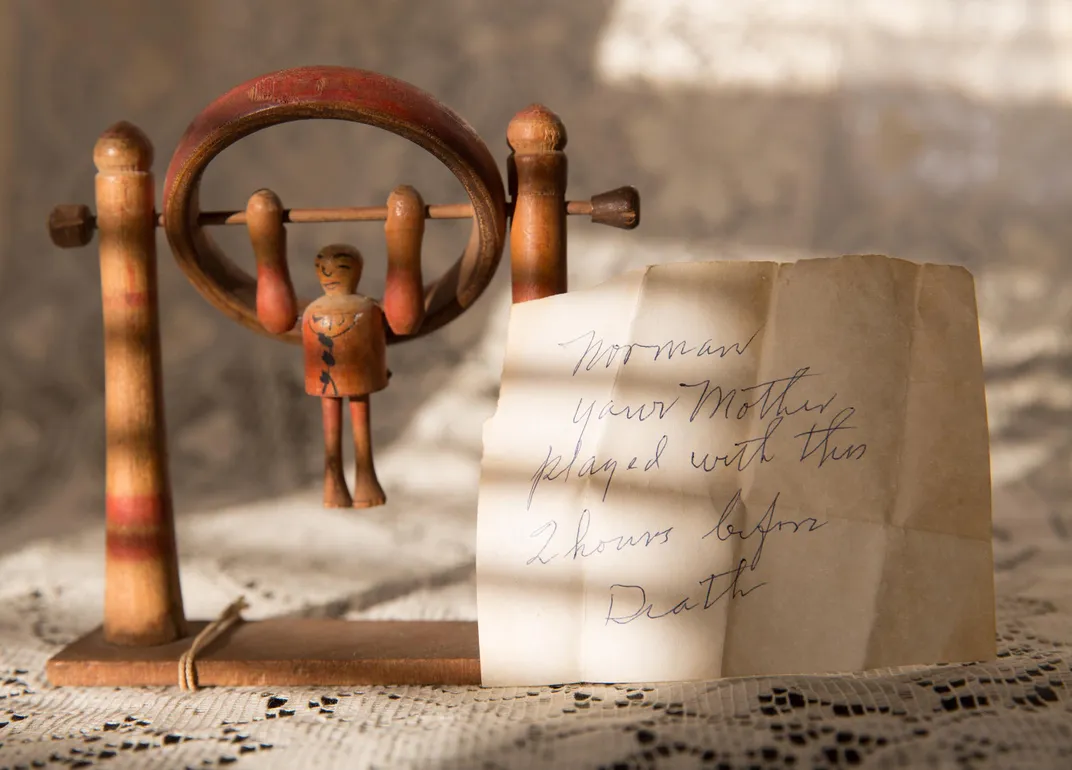

A piece I really love is what I call the "Somber Toy" from Calvin Von crush's collection. It's just this little wooden toy that when you squeeze it, the character in the center flips over. Then there's a note that came with the piece that reads: "Your mother played with this two hours before death."

It just turns the whole thing. You think you're looking at this little toy and it's cute. But it just becomes so sad. You could imagine the son or the daughter just looking at this thing, thinking: This is the last thing my mother touched when she was alive.

What started your obsession with death?

When I was very young, my grandmother got really sick. She didn't die, but the pall of death hung over the house forever. It doesn't take much psychoanalyzing to realize that that's why I collect.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/9c/c19c3c89-6736-40fb-bc49-c6ca444143a3/stella.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)