Meet the Tiny Killer Causing Millions of Sea Stars to Waste Away

The deadly sea star wasting disease, which turns live animals into slimy goop, is caused by a previously unknown virus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/f3/06f3cb03-5d30-46b6-985b-d19bb4d145a6/sunflower.jpg)

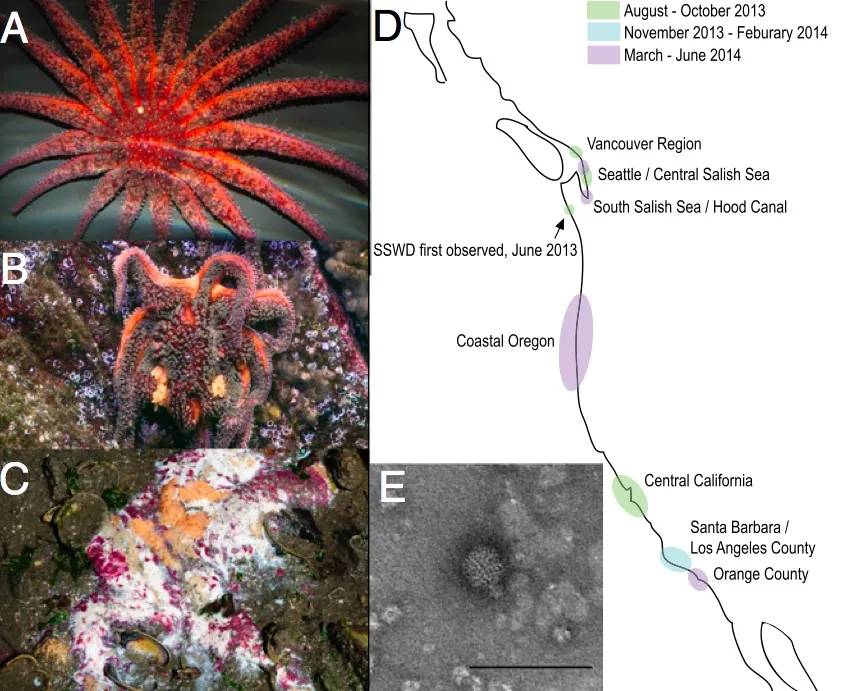

Last year, a plague broke out in the Pacific. From Alaska to Mexico, millions of sea stars from 20 different species contracted a mysterious disease that condemns nearly 100 percent of its victims to a horrific death. First the sea stars become lethargic. Then their limbs start curling in on themselves. Lesions appear, some of the sea stars' arms might fall off and the animals go limp. Finally, like something straight from the set of a horror movie, an infected sea star undergoes “rapid degradation”—the scientific term for melting. All that is left is a pile of slime and a few pieces of invertebrate skeleton.

Despite the magnitude of the loss, no one knew what was behind the condition, known as sea-star wasting disease. Now a culprit has finally been identified: a virus that has been targeting marine animals for at least 72 years. A large team of American and Canadian researchers revealed the killer today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Scientists first described the sea star disease in 1979, but past epidemics mostly affected just one or a few species and were confined to small, isolated patches of ocean along the West Coast. Scientists put forth various hypotheses over the years to explain the phenomenon, ranging from storms to temperature changes to starvation. Some speculated that an unidentified pathogen might be driving the outbreaks, noting that the outbreak's spread followed the same patterns as an infectious disease. But if that hunch were true, researchers still needed to find out whether it was caused by bacteria, parasites or a virus.

The pathogen hypothesis gained traction in 2013, when the wasting disease broke out not only in California’s marine environments but in its aquariums too. Notably, aquariums that used ultraviolet light to sterilize incoming seawater escaped the epidemic of death. This indicated that the wasting disease had microbial origins, so the study authors began to use the process of elimination to identify the pathogen. After examining hundreds of slides of melted starfish tissue, they found no indication of bacteria or parasites. A virus, they concluded, must be behind the outbreak.

The team decided that an experiment was the fastest way to test the virus hypothesis, so they collected sunflower sea stars from a site in Washington State where the wasting disease had yet to take hold. They placed the sunflower sea stars in different tanks, each of which was supplied with UV-treated, filtered seawater. Then they took tissue samples from infected sea stars and injected the sunflower sea stars with those potentially deadly concoctions. Some of the samples, however, had been boiled to render any viruses in them sterile.

Ten days after being inoculated with the potentially infectious material, the sunflower sea stars began to show the first telltale signs of the wasting disease. Those that had received the boiled samples, however, remained healthy. Just to be sure, the team took samples from the newly infected sunflower sea stars and used them to infect a second batch of victims. Sure enough, the same pattern emerged, with sea stars becoming sick within about a week.

With that damning evidence in hand, the next step was to identify the virus. The researchers genetically sequenced and sorted the infected sea stars’ tissue. Those analyses yielded a nearly complete genome of a previously unknown virus, which the researchers named sea star-associated densovirus. This virus is similar to some diseases known to infect insects and also bears genetic resemblance to a disease that sometimes breaks out among Hawaiian sea urchins.

The team did not stop there. To ensure that the virus was indeed the killer, they sampled more than 300 wild sea stars that were either infected or not showing any symptoms and measured their viral load. Those that had the disease had a significantly higher number of viruses in their tissue than those that were disease-free, they found. They also discovered the virus in plankton suspended in the water, in some sediment samples and in some animals that weren't displaying symptoms such as sea urchins, sand dollars and brittle stars. This suggests that the microbe might persist in various environmental reservoirs, even when it’s not breaking out in sea stars. The team even found the virus in museum specimens dating back to 1942, suggesting that it has been around for at least seven decades.

Now that the viral killer has been identified, the researchers are left with some crucial questions. What triggers the virus to suddenly emerge, and how does it actually go about killing the sea stars? Why do some species seem immune, and why has this latest epidemic been so severe compared to past outbreaks? Is there any way to prevent the disease from completely wiping out the West Coast’s sea stars?

The researchers have a few hunches. Divers in 2012 reported a sunflower sea star overload in some marine environments, so it could be that the unusual surplus of animals spurred a particularly frenzied outbreak. It's also possible that the virus recently mutated to become more deadly than it was in the past. The scientists note that these are all just guesses, but at least now they know where to look to start looking for answers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)