The Lady Anatomist Who Brought Dead Bodies to Light

Anna Morandi was the brains and the skilled hand of an unusual husband-wife partnership

:focal(536x158:537x159)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/5f/2b5fc3f7-30ff-4189-b316-0aa03f46c7d1/484px-annamorandimanzolini-wr.jpg)

Anna Morandi stands in the middle of her home laboratory, wielding a curved knife. Dressed in a long cowl to fend off the stench of putrefying flesh, the 18th century teacher and anatomist scrapes clean the bones of the human corpse before her; she will soon animate its likeness in soft wax. She works swiftly and skillfully, surrounded by both the surgical instruments of an anatomist and the tools of an artist.

In Morandi’s 18th-century Bologna, it would have been unusual, to say the least, to watch a woman so unflinchingly peel back the skin of a human body. Yet Morandi did just that, even drawing the praise of the Bolognese Pope’s for her efforts to reveal the secrets of vitality and sensation concealed beneath the skin. Working at the delicate intersection of empirical science and the artistic rendering of the human body, Morandi helped elevate her city as a hub of science and culture.

As an anatomist, Morandi went where no woman had gone before, helping to usher in a new understanding of the male body and developing new techniques for examining organs. She also served as the public face of an unusual scientific partnership with her husband, a sculptor and anatomist. Yet in one way, she was no exception to what has become a common narrative of historical women in science: Despite her achievement and acclaim during her lifetime, her role was ultimately written out of history.

A husband-wife partnership

When the 26-year-old Morandi married artist and wax sculptor Giovanni Manzolini in 1740, Bologna was undergoing a resurgence of intellectual ascendancy. Bolognese politicians and nobleman—namely Pope Benedict XIV—worked to restore the city to its former glory. With the gradual decline of the city’s university and intellectual culture, it had fallen into disrepute in the eyes of the Western world.

The way to reverse the decline of the city, Pope Benedict believed, was to invest in medical science, particularly the then-“new” empirical science of anatomy. Before the Renaissance, anatomy largely meant philosophizing and relying on ancient texts like those of Roman physician Galen—rather than the measurable and observable evidence of hands-on human dissection. By the 18th century, there was still much to discover of the human body.

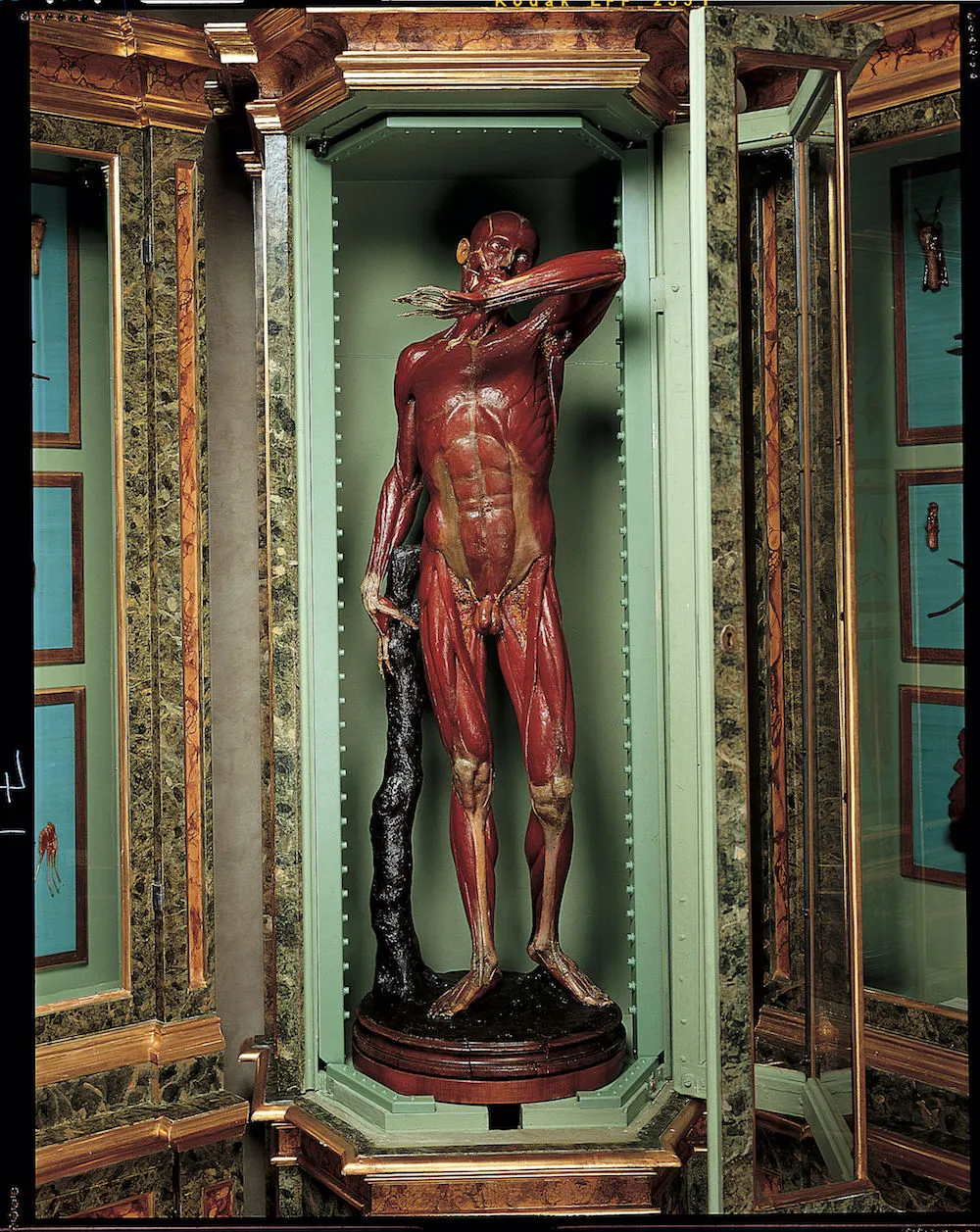

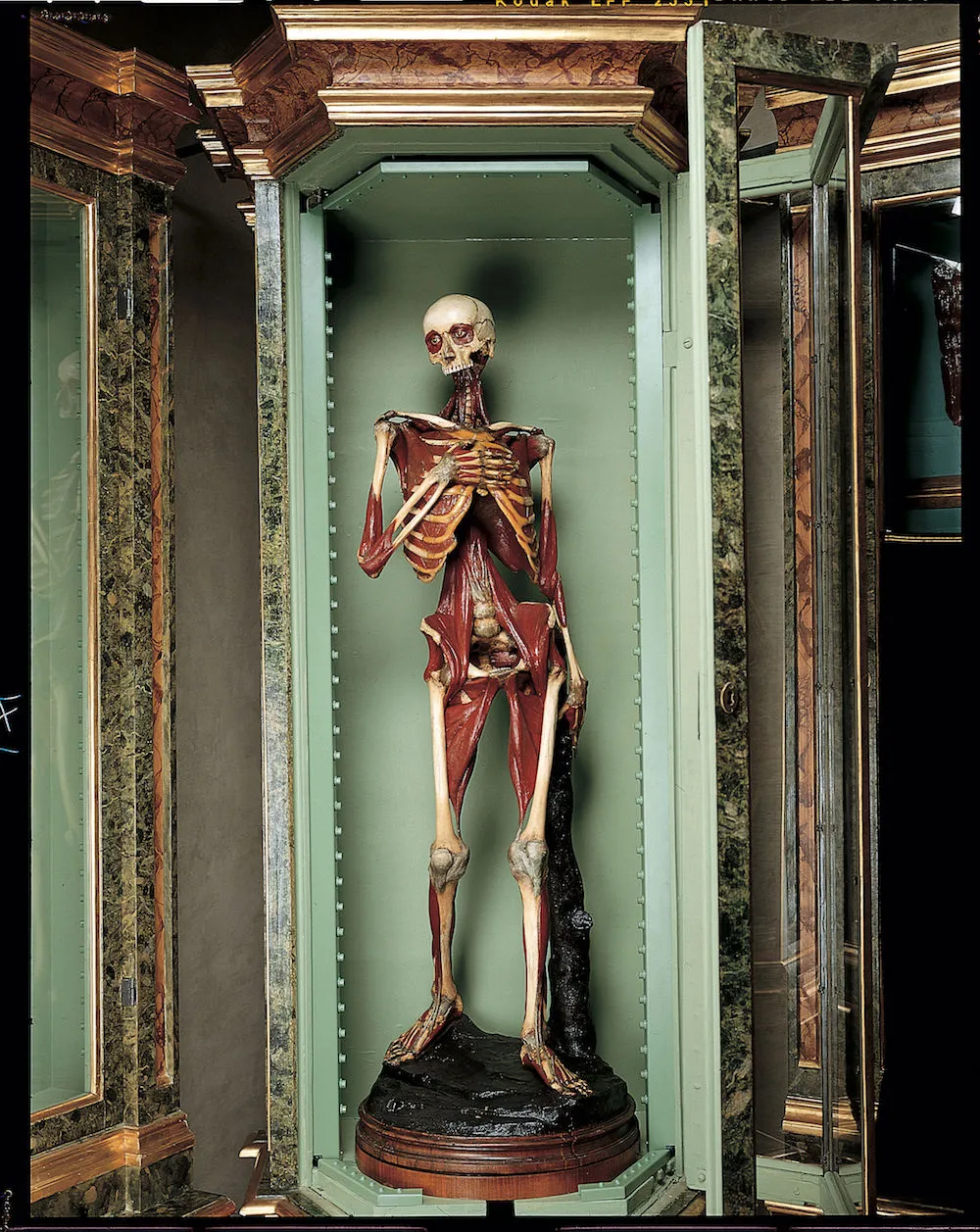

Morandi and Manzolini helped lead this resurgence in Bologna. Together, the two dissected hundreds of corpses and created hundreds more anatomical wax sculptures. They also pioneered a novel method: Instead of approaching the whole body for dissection and study as other anatomists did, the pair systematically extracted organ systems for further bisection and isolated study. This meticulous method allowed them to create detailed wax models of individual organ systems ideal for teaching students of anatomy.

The couple’s home served both as a dissection lab and public classroom. Morandi taught hundreds of students of anatomy with her wax models and from her own Anatomical Notebook, which contained 250 handwritten pages of instruction, notes and descriptions of corresponding wax models. Because of her extensive collection of wax models, she could teach anatomy lessons year round without worrying about the decay of dissected corpses in the heat of an Italian summer.

Unlike other husband-wife scientific partnerships, Morandi was the public face of their operation. As a woman who effortlessly handled dead bodies and skillfully re-created life with wax, she was an object of great intrigue in Bologna and abroad. Morandi attracted international tourists visiting her studio to see and hear the Lady Anatomist, and she even caught the attention of Empress Catherine the Great, who asked Morandi to be part of her court (a request Morandi declined, for reasons unknown).

Morandi also received praise and recognition from her Bolognese Pope. The Pope was likely interested in matters besides anatomical science and medicine: By creating the public and artistic display of the exposed inner workings of a body’s muscles and tissue, organs and arteries, anatomists and sculptors like the Morandi-Manzolini team brought prestige to the city and lifted up its international reputation.

This work required scientific expertise, but it also required something else: artistic imagination, the ability to recreate bodies and bring them to life.

Where no woman had gone

Morandi had a special interest in the mechanisms of sensory experience: She sought to understand and capture how the eyes, ears and nose each experienced its particular sense. In her series on the eye, she deconstructs the visual organ completely and then systematically reimagines it in wax in five separate panels. Starting from the surface, she shows an isolated eye of a nameless face looking in six different directions, and each panel gradually reveals a new component layer behind the skin.

This meticulous method of deconstructing and reconstructing sensory experience led her to discover that the oblique eye muscle attaches to the lachrymal sac as well as the maxillary bone, which ran against what other anatomical experts said at the time. Her observations were correct, a triumph that spoke to her meticulous methodology. “This was discovered by me in my observations and I have found it always to be constant,” she wrote in her notebook.

Morandi’s other special interest was the male reproductive system, to which she devotes a full 45 pages in her notebook. This was unusual because, at the time, most anatomists were more interested in the female anatomy. In Secrets of Women: Gender Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection, writer Katherine Park shows that the womb was of particular fascination to anatomists as it became a “privileged object of dissection in medical images and texts … the uterus acquired a special, symbolic weight as the organ that only dissection could truly reveal.”

But while most anatomists, predominantly men, extensively studied the female reproductive system as a mysterious cauldron of life, Morandi turned her gaze to the male role in reproduction. Though her wax models of the male reproductive system have been lost, historian and Morandi biographer Rebecca Messbarger says that Morandi’s notebook shows the depth and detail of her study—even down to the microscopic substances of the reproductive system.

Unsurprisingly, some objected to a woman gazing so unabashedly at the mysteries of life that had previously been reserved for men. Messbarger specifically calls out anatomist Petronio Ignazio Zecchini, who believed Morandi and other women intellectuals to an interloper in his profession and who sought to undermine their authority through gendered attacks. In his book Genial Days: On the Dialectic of Women Reduced to Its True Principle, he claims that women are ruled by their uterus, not their brains and intellect like men, and tells women to “[w]illingly subject yourselves to men, who, by their counsel, can curb your instability and concupiscence.”

Despite the international recognition and the notoriety in Bologna, Morandi was not exempt from the gender realities of the time. Like other women scientists in her era, she made significantly less money than male scientists for the same work. She struggled financially, even to the point of giving up her eldest son to an orphanage. Although she continued to sell her wax models and received a small stipend from the city Senate, she was unable to sustain financial independence.

Written out of history

Despite Morandi’s publicity and celebrity, she has been lost to history. Messbarger has a theory as to why.

Contemporary writer Francesco Maria Zanotti described Morandi in gendered terms to underscore her femininity: “A very beautiful and very ingenious woman deals in a novel manner with cadavers and already decaying limbs … this woman embellished the house of the human body … And most eloquently does she explain them to those who flock to her…” Other contemporary writers like Luigi Crespi explain Morandi’s scientific skills, however, as result of devotion to her husband, describing her as "his wise and pious wife."

Messbarger says that these contemporary descriptions of Morandi as first a woman assistant and devoted wife “have influenced her place in history to her detriment. She was essentially erased from history,” Messbarger says, “Morandi had an international reputation. But even later biographical sketches represent [Manzolini] as the brains, and she was the gifted hand. In her lifetime, that wasn’t true.”

In her book on Morandi, The Lady Anatomist, Messbarger looks to Morandi’s Anatomical Notebook and letters where she finds that Morandi was not merely the assistant or eloquent teacher of Manzolini’s genius; she believes that they were genuine partners. The work that Morandi continued to produce after Manzolini’s death in 1755 shows that Morandi’s scientific knowledge and artistic skill with wax even surpassed that of her late husband and partner.

Morandi’s response to such attacks on her is best encompassed in her own wax self-portrait. Messbarger identifies three 18th century trends in anatomized images of women: a seductive, intimate Venus, a shamed downward-looking Eve or a dead female cadaver. In her self-portrait, Morandi sees herself as none of these. Instead she looks straight and steady, wearing feminine aristocratic dress, as she wields a scalpel over a human brain: the manifestation of male intellect.

Alongside her self-portrait, Morandi memorialized her late husband in wax, who she cast in a more feminine posture, looking down to the side, with his hand on a human heart—the symbol of female emotion. Messbarger says that Morandi’s subversion of gender norms in her and her husband’s wax portraits was consciously executed.

“That a woman would be dissecting a human brain in her self-portrait, there is no way that would not be a provocation,” she says. “And then to show her husband dissecting the seat of sentiment.” Morandi was pushing back against the gender biases that associated women with sentiment and men with intelligence—showing once and for all that she was both the brains and the skilled hand in this unusual wife-husband endeavor.