Why the World Needs to Go to Great Heights to Save Mountain Habitats

After 30 years working in mountain regions, Jack Ives argues that the world’s elevated habitats are essential

Jack Ives has met His Holiness John Paul II and has been ambushed by bandits. He has dined with the king and queen of Thailand and been followed by the Chinese secret police—all in the name of mountain research.

Fueled by a boyhood love for mountains, Ives embarked on an academic career in geography beginning in the 1960s, which launched him onto the world stage in a political struggle over how these habitats and their inhabitants are perceived. In time, he became a pivotal force in bringing to the world's attention the importance of mountainous regions to an environmentally sustainable future.

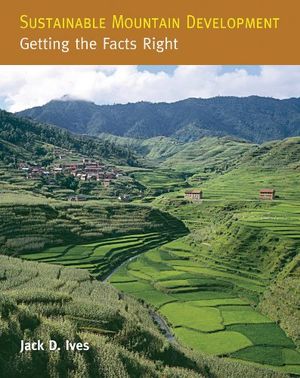

Today, much of the conversation about climate change and sustainable development tends to focus on polar ice and the rainforests, and mountains still don't receive the full attention they deserve, Ives says. In his recent book, Sustainable Mountain Development: Getting the Facts Right, he details his efforts to include mountain regions in environmental legislation before and after the pivotal 1992 Rio Earth Summit. Here is why Ives thinks it is imperative that elevated regions remain in the picture for sustainability, and what he hopes for the future of mountain development:

Who or what inspired you to sit down and write this book?

It was really a conviction. I’m referring to colleagues of long standing … but also world leaders that I had the privilege of meeting. I felt that bringing that all together in the context of what was really a major political and research effort should be on the record.

Of the many anecdotes that you share in the book, which one best illuminates the joys or challenges of developing a mountain agenda?

I did my undergraduate work in England, and my dream was to organize expeditions to Arctic mountain areas. The place I chose was Iceland, and this led me to living on a rather poor sheep farm for quite long periods of time and getting to know the people and especially the farmer. I learned from him that my clever university learning could nowhere near match his understanding of the ecology of the surrounding environment on which he depended. Years later, ... [my colleagues and I] had a growing feeling that we have so much to learn from these wonderful mountain people who have been very much abused. They’re not ignorant. There is an enormous amount of ethological and environmental knowledge—and the experience of surviving in difficult environments—which is now coming into the main flow of knowledge.

In light of that, what is important for people to understand about the mountains and how they fit into the larger conversation about the environment?

We refer to the mountains as water towers of the world. Most of the major rivers of the world are supplied from heavy rainfall in the mountains and melting snow. If you mess up the mountain environment, you are going to impact the plains. Twenty percent of the Earth’s terrestrial surface is mountainous, and the mountains provide the living means for about 10 percent of the human population. If mountains are badly handled, as in many places they are, then the impact is far greater than just on that part of the world that is mountainous, because the downstream effects are properly going to be more serious than the effects in the mountains themselves.

You say that the students of this first group of mountain academics, and their students, are now “guardians of the mountains.” What is their task?

I would need to write a book on that question. Each country tends to have different problems, but creating awareness and giving credibility to the intelligence and determination of the mountain people themselves—I think this is the thing that we’ve helped lay the foundation for. There is an enormous increase in awareness, and the students that have worked with me are themselves teaching courses in mountain geography. When I was teaching in Boulder, Colorado, up until 1989, I don’t think there were more than three courses in mountain geography per se in the whole of North America. In my old-age wisdom, I have to realize that you don’t change the world in a few years. I just hope that we can change it sufficiently more before dreadful things like climate change and terrorism catch up with us.

What has been the most rewarding moment of your career?

This broad experience of finding a group of friends from all over the world. There’s been an international partnership of all shapes and colors, and we have developed this kind of community spirit, and I think this has been the great personal experience of my life.

I have to ask—what is the most beautiful place you have visited, with regard to the mountains?

Well, that is difficult to answer. We had our 60th wedding anniversary in Switzerland last year in the Emmental—that’s a farming community between the capital city of Bern and the Swiss Alps—where the buildings are 300-year-old farmhouses surrounded by flowers. That’s where I had my sabbatical year in 1976-77, and basically it was from that sabbatical year that what we’ve been talking about grew. I love mountain landscapes, but the real beauty is where you have this incredible mix of careful maintenance of landscape within a mountain setting. That to me is beauty—with the people included.

Sustainable Mountain Development: Getting the Facts Right