The Iceman’s Stomach Bugs Offer Clues to Ancient Human Migration

DNA analysis of the mummy’s pathogens may reveal when and how Ötzi’s people came to the Italian Alps

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/55/3355cfef-512d-41b8-a2ae-29456cdd29ce/maixner2hr.jpg)

It turns out Ötzi the legendary “Iceman” wasn't alone when he was mummified on a glacier 5,300 years ago. With him were gut microbes known to cause some serious tummy trouble.

These bacteria, Helicobacter pylori, are providing fresh evidence about Ötzi's diet and poor health in the days leading up to his murder. Intriguingly, they could also help scientists better understand who his people were and how they came to live in the region.

“When we looked at the genome of the Iceman's H. pylori bacteria, we found that it's quite a virulent strain, and we know that in modern patients it can cause stomach ulcers, gastric carcinoma and some pretty severe stomach diseases,” says Albert Zink of the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman at the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano (EURAC) in Italy.

“We also found proteins that are very specific and only released if you have an inflammatory response, so we can say that he most probably had a quite severe H. pylori infection in his stomach," Zink adds. "However, we simply don't have enough of the stomach structure, the stomach walls, to determine the extent to which the disease impacted his stomach or how much he really suffered.”

Discovered in the 1990s, Ötzi lived in what are today the Eastern Italian Alps, where he was naturally mummified by ice after his violent death. The body is astonishingly well preserved and has provided scientists with a wealth of information about the Iceman's life and death during the Copper Age.

For instance, various examinations have revealed his age, how he died, what he wore and what he ate. We know he suffered from heart and gum disease, gallbladder stones and parasites. His genome has been studied, relatives have been found and his 61 tattoos have been mapped.

The latest discovery not only adds to the Iceman's health woes, it offers hints of human migration patterns into Europe. While not everyone has H. pylori in their guts, the bacteria are so frequently found in human stomachs that their evolution into different strains can be used to help reconstruct migrations going back about 100,000 years.

Global patterns of H. pylori variants have already been found to match existing evidence of prehistoric human migrations. Bacterial analysis related to the peopling of the Pacific, for example, mirrors language distribution of migrants across this vast region. And movements of people known from the historical record, such as the transatlantic slave trade, have been found to match the bacteria's genetic variance.

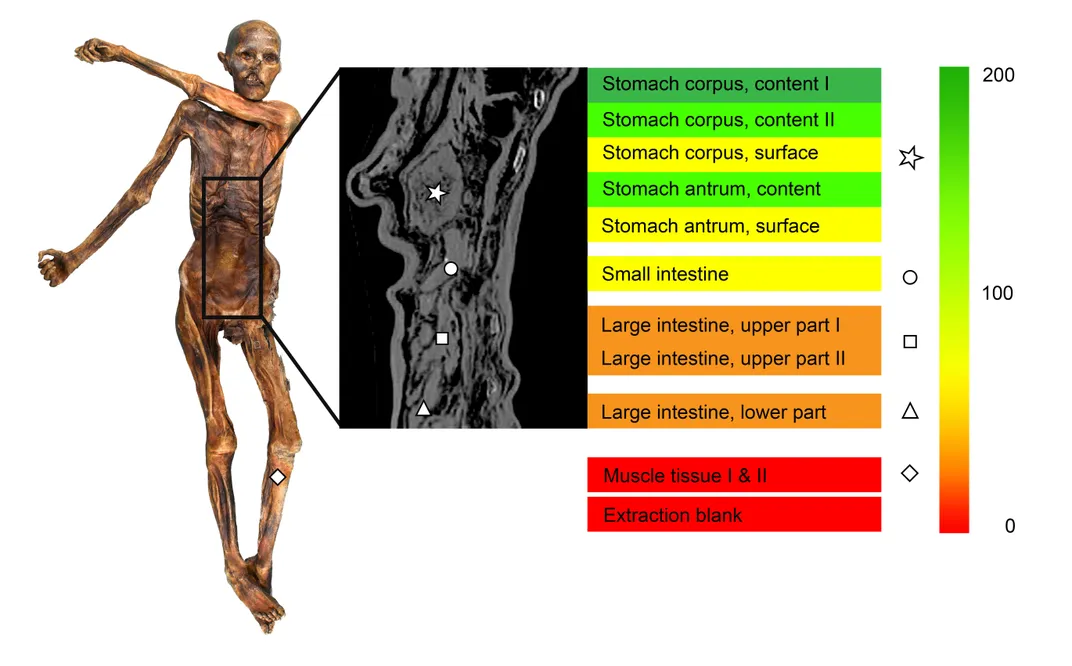

To study the Iceman's gut bugs, Zink and colleagues completely thawed the mummy and used an existing incision from previous research to take 12 biopsies from the corpse, including the last foods he ate and parts of his stomach and intestines.

What they found was a surprisingly pure strain of the stomach bug that's closely related to the version found in modern Asian populations. By contrast, the modern European strain of H. pylori seems to be a mix of Asian and African ancestral strains. This provides evidence that pure African populations of the bacteria arrived in Europe only within the past few thousand years.

“Based on what we knew before, it was believed that the mixture of the ancestral African and Asian strains had already occurred maybe 10,000 years ago or even earlier,” Zink says. “But the very small part of African ancestry in the bacteria genome from the Iceman tells us that the migrations into Europe aren't such an easy story.”

The iceman's unmixed stomach bacteria are “in line with recent archaeological and ancient DNA studies that suggest dramatic demographic changes shortly after the Iceman’s time, including massive migration waves and significant demographic growth,” co-author Yoshan Moodley of the University of Venda, South Africa, told assembled press during a briefing on Wednesday.

“These and later migration waves were definitely accompanied with newly arriving H. pylori strains that recombined with already present strains to become the modern European population.”

More than a decade ago, Daniel Falush of Swansea University and his colleagues published a study suggesting that H. pylori has ancestral populations that arose separately in Africa, Central Asia and East Asia, and that modern strains were created by when these populations mixed via human migrations around the globe.

“Back in 2003 we made this sort of wild claim that European H. pylori were a hybrid, mixed from one Asian source and one African source. That was thought to be quite a funny thing for bacteria at the time,” Falush notes.

“But now they've gone back more than 5,000 years in time and found that Ötzi had bacteria that's nearly purely representative of that Central Asian strain. So it seems that the prediction we made entirely by a statistical algorithm, that later bacteria were mixed, seems to be proven correct now that we have an ancient source.”

The question now is how the ancestral African strain arrived in Europe, Falush adds. “We originally guessed it was during the Neolithic migration [around 9,000 years ago], but it appears that was wrong, because this genome says it probably happened within the past 5,000 years."

Once it arrived, the African strain must have been particularly successful, since it spread right through Europe, he adds. "But it's far from obvious why an African bacterium would spread this way. Why was it successful, and what were the patterns of contact between people?”

These are exactly the kinds of mysteries future studies of the Iceman, and his gut bacteria, might help solve.