Huge Wine Cellar Unearthed at a Biblical-Era Palace in Israel

Residue from jars at a Canaanite palace suggest the ruler preferred his red with hints of mint, honey and juniper

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/45/cb45880b-87f3-45b5-9511-5701961d3bc4/winecellar7.jpg)

The wine is robust but sweet, with herbal notes and maybe a hint of cinnamon. Carefully stored in a room near the banquet hall, dozens of large jugs filled with the latest vintage sit waiting for the next holiday feast or visiting politician. Then, disaster strikes. An earthquake crumbles walls and shatters jars, spilling waves of red fluid across the floor and leaving the grand wine cellar in ruins.

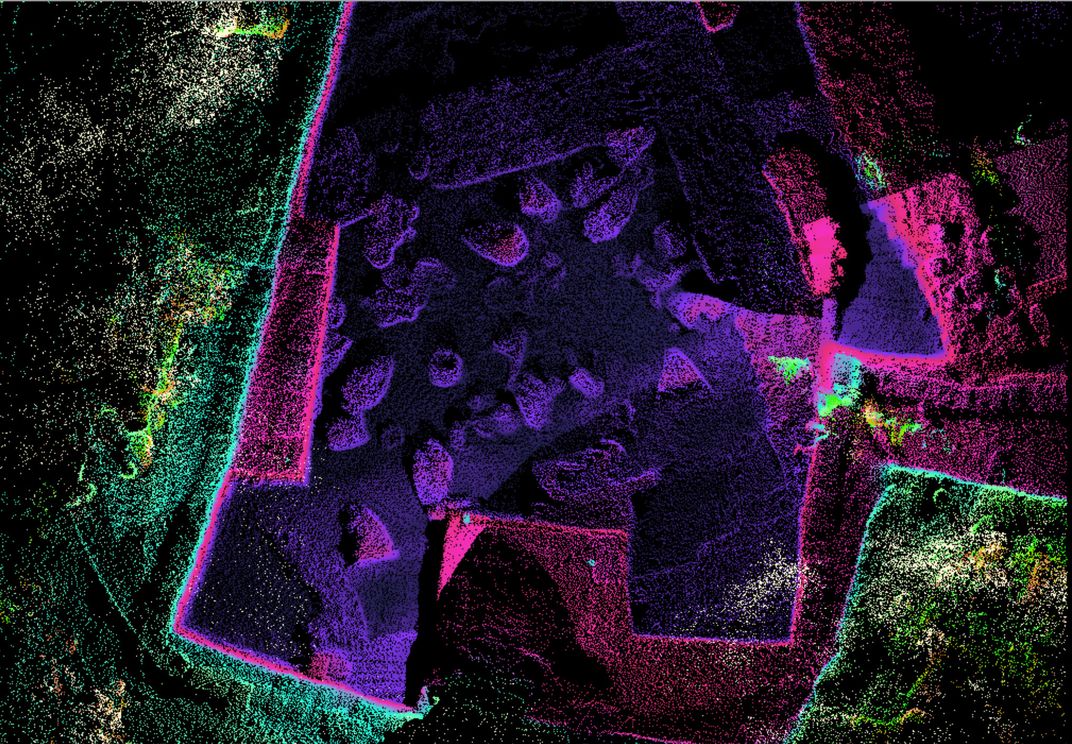

This isn’t a vineyard villa in Napa—it’s one possible explanation for recent discoveries in the Canaanite palace of Tel Kabri, in the northwestern part of modern-day Israel. The remains of 40 large jugs found at the site show traces of wine infused with herbs and resins, an international team reports today in the journal PLOS ONE. If their interpretation holds up, the room where the vessels were found may be the largest and oldest personal wine cellar known in the Middle East.

“What’s fascinating about what we have here is that it is part of a household economy,” says lead author Andrew Koh, an archaeologist at Brandeis University. “This was the patriarch’s personal wine cellar. The wine was not meant to be given away as part of a system of providing for the community. It was for his own enjoyment and the support of his authority.”

Various teams have been excavating Tel Kabri since the late 1980s, slowly revealing new insights into life during the Middle Bronze Age, generally considered to be between 2000 and 1550 B.C. The palace ruins cover about 1.5 acres and include evidence of monumental architecture, food surpluses and complex crafts.

“Having a Middle Bronze Age palace isn’t all that unusual,” says Koh. “But this palace was destroyed toward 1600 B.C.—possibly by an earthquake—and then it goes unoccupied.” Other palaces in the region that date to around the same time had new structures built on top of the originals, clouding the historical picture. “We would argue that Kabri is the number-one place to excavate a palace, because it has been preserved,” says Koh. “Nothing else is happening over top that makes it difficult to be that archaeological detective.”

The team unearthed the wine cellar during excavations in 2013 and described their initial analysis at a conference this past November. In the new paper, Koh and his colleagues outline their methods and offer some context to help back up the claim.

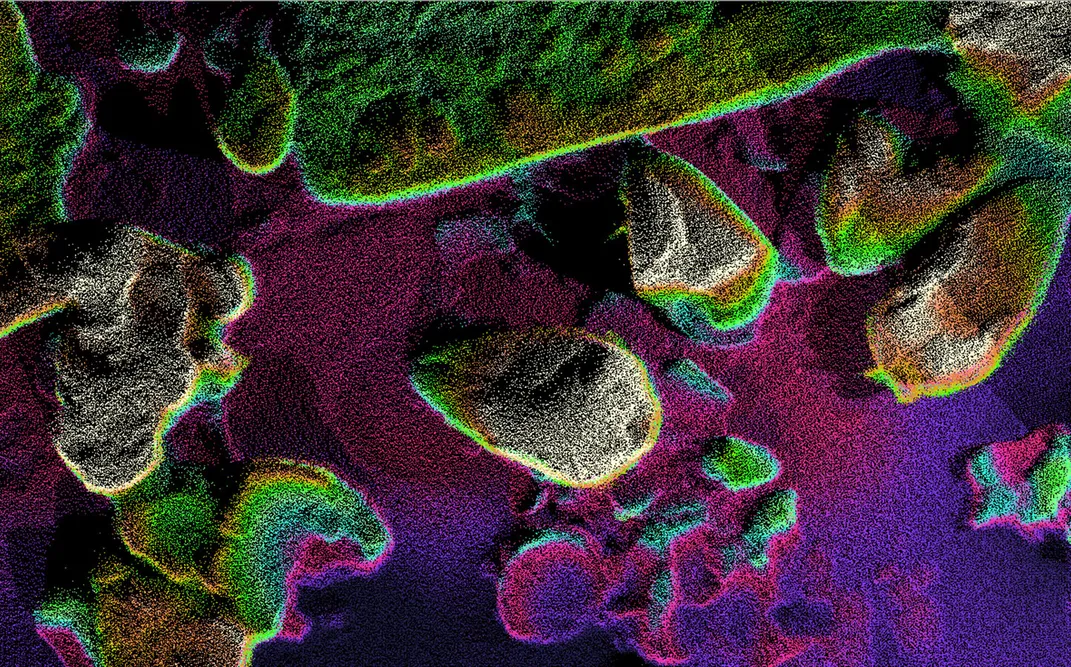

The room holds the remains of 40 large, narrow-necked vessels that could have held a combined total of 528 gallons of liquid—enough to fill 3,000 modern bottles of wine. There is a service entrance and an exit connected to a banquet hall. The team says that samples of 32 jars brought back to the lab in Massachusetts all contained traces of tartaric acid, one of the main acids found in wine. All but three of the jars also had syringic acid, a compound associated with red wine specifically.

Residue in the jars also showed signs of various additives, including herbs, berries, tree resins and possibly honey. This would fit with records of wine additives from ancient Greek and Egyptian texts, the team says. Some of these ingredients would have been used for preservation or to give the wine psychotropic effects. “This is a relatively sophisticated drink,” says Koh. “Somebody was sitting there with years if not generations of experience saying this is what best preserves the wine and makes it taste better.”

However, finding tartaric and syringic acids doesn’t definitively mean you’ve found wine, says Patrick McGovern, a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania and an expert in ancient alcohol. Both acids are also found naturally in other plants or can be produced by soil microbes. “It’s good they did a soil sample, because microorganisms do produce tartaric acid in small amounts, and they did not see in the soil,” McGovern says.

He also expressed some concern that the team’s traces from the ancient jars are not a perfect match for the modern reference samples used in the study. A few extra steps in the chemistry could verify the link between the acids and wine grapes, he says. Still, assuming the residue tests stand up, the results fit well with other evidence for wine making in the Middle East, he says. Previous discoveries suggest that wine grapes were first grown in the neighboring mountains and moved south into the region around Tel Kabri by the middle of the 4th millennium B.C. Records from the time show that by the Middle Bronze Age, Jordan Valley wine had become so celebrated that it was being exported to the Egyptian pharaohs.

So what would modern-day oenophiles make of the Tel Kabri wine? It may be an acquired taste. “All wine samples from different parts of the Near East have tree resin added, because it helps keep the wine from going to vinegar,” notes McGovern. “In Greece, they still make a wine called Retsina that has pine resin added to it. It tastes really good once you start drinking it. You get to like it, similar to liking oak in wine.” And McGovern has had some commercial success bringing back ancient beers—“Midas Touch” is an award-winning re-creation of beer from a 2700-year-old tomb found in Turkey.

If Koh and his team have their way, a Tel Kabri label could also make it to store shelves. “We’ve talked to a couple vineyards to try and reconstruct the wine,” says Koh. “It may not be a huge seller, but it would be fun to do in the spirit of things.” The scientists are even hoping they will be able to recover grape DNA from future samples of the jars, which might bring them closer to a faithful reconstruction of the ancient wine.

“Celebrated wines used to come from this region, but local wine making was wiped out with the arrival of Muslim cultures [in the 7th century A.D.],” says Koh. “Most grape varieties growing in Israel today were brought there by [French philanthropist Edmond James] de Rothschild in the 19th century.” Grape DNA from Tel Kabri could help the team track down any feral grapes growing in the region that are related to the Bronze Age fruit, or perhaps figure out which modern varietals in Europe are closest to the ancient beverage.

*This article has been updated to correct the area of the palace ruins.