How Male Elephants Bond

Bull elephants have a reputation as loners. But research shows that males are surprisingly sociable—until it’s time to fight

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Elephants-Etosha-National-Park-631.jpg)

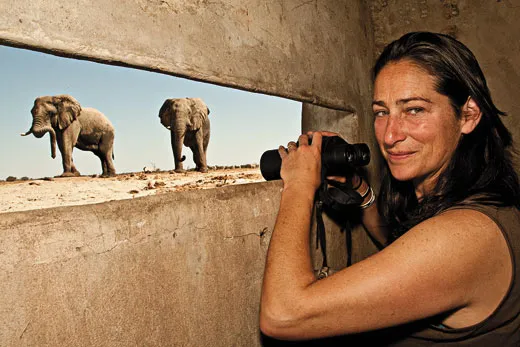

While sipping tea one morning and enjoying the expansive view of a water hole from my 25-foot-tall research tower, I could see a storm of epic proportions brewing.

My colleagues, students, volunteers and I were at Mushara, a remote water source in Namibia’s Etosha National Park, to study the dynamics of an all-male society, bull elephant style. I’d been coming to this site for 19 years to study elephants, and the complexity of the bulls’ relationships was becoming more and more striking to me.

Male elephants have a reputation as loners. But in Amboseli National Park in Kenya, where the longest-running studies on male elephants have been conducted, bulls have been observed to have a best friend with whom they associate for years. Another study, in Botswana, found that younger males seek out older males and learn social behaviors from them. In my previous field seasons at Mushara, I’d noticed that males had not just one close buddy but several, and that these large groups of males of mixed ages persisted for many years. Of the 150 bulls that we were monitoring, the group I was particularly interested in, which I called the “boys’ club,” comprised up to 15 individuals—a dominant bull and his entourage. Bulls of all ages appeared remarkably close, physically demonstrating their friendship.

Why was this group so large and its members so tight? What held them together? And how was dominance decided and maintained? Now, as I trained my binoculars at the water hole, I looked for answers to these questions, and witnessed a showdown.

Like many other animals, elephants form a strict hierarchy, which reduces conflicts over scarce resources such as water, food and mates. At Mushara, an artesian well provides the best water, which is funneled into a concrete trough—a remnant of an old cattle farm built before this area was incorporated into the park. The outflow of the well at the head of the trough, which has the cleanest, most palatable water and is equivalent to the head of a table, was clearly reserved for the top-ranking elephant—the one I referred to as the don.

As five members of the boys’ club arrived for a drink, I quickly noticed that two young, low-ranking bulls weren’t up to their usual antics. Jack and Spencer, as I called them, were agitated. They kept shifting their weight and seemed desperate for reassurance, with one or the other holding his trunk out tentatively, as if seeking comfort from a higher- ranking bull’s ritualized trunk-to-mouth greeting.

Keith and Stoly, more senior bulls, ignored these attempts at engagement. They offered no reassuring gestures such as a trunk over a youngster’s back, or an ear over a head or rear. Instead, they and the younger bulls seemed to be watching Greg, the don. And he was obviously in a foul temper.

Greg, about 40 years old, was distinguishable by two square notches out of the lower portion of his left ear. But there was something else, something visible from a long way off, that identified him. This guy had the confidence of a general—the way he held his head, his casual swagger. And for years now, whenever Greg strutted up to the water hole, the other bulls slowly backed away to allow him access.

When Greg settled in to drink, each bull in turn approached him with an outstretched, quivering trunk, dipping the tip into Greg’s mouth as though kissing a human don’s ring. After performing this ritual and seeing a placated Greg, each bull’s shoulders seemed to relax and each slouched submissively away from Greg’s preferred drinking spot.

It was a behavior that never failed to impress me—one of those reminders that human beings are not as unique in social complexity as we like to think. This culture was steeped in ritual.

Despite the other males’ deference, Greg still seemed agitated. He fitfully shifted his weight from one front foot to the other and spun his head around to watch his back and give his best stink eye to some phantom pursuer, as if somebody had tapped him on the shoulder in a bar, trying to pick a fight.

I scanned the horizon to see if any more bulls were heading our way. Considering Greg’s increasing agitation, I thought he might be sensing an approaching rival. In my earlier research here, I’d discovered that elephants can hear rumbles too deep for human hearing and use their feet and trunks to sense rumbles that travel through the ground for miles. Elephants can even recognize one another through these vibrations.

Perhaps Greg sensed a bull in musth. A male entering the hormonal state of musth is supposed to experience a kind of Popeye effect—the equivalent of downing a can of spinach—that trumps established dominance patterns. Not even an alpha male would risk challenging a bull elephant with a heightened level of testosterone. Or so I thought.

An elephant in musth is looking for a mate with such singularity of purpose that he hardly takes the time to eat or drink. He engages in exaggerated displays of aggressiveness such as curling the trunk across the brow with ears waving—presumably to facilitate the wafting of a sticky, musthy secretion from temporal glands above the cheek, just behind the eye—while excreting urine, sometimes to the point of gushing. The message is the elephant equivalent of “don’t even think about messing with me ’cause I’m so crazy-mad that I’ll tear your head off.” Other bulls seem to understand this body language quite well.

While Greg twitched, the mid-ranking bulls were in a state of upheaval. Each seemed to be showing his good relations with higher-ranking individuals: Spencer leaned against Keith on one side, and Jack on the other, placing his trunk in Keith’s mouth—Keith being a favorite of the don. The most sought-after connection was with Greg himself, who often allowed certain privileged lower-ranking individuals to drink right next to him.

But today Greg was in no mood for brotherly backslapping. Stoly, who ordinarily enjoyed Greg’s beneficence, cowered in the overflow from the trough, the lowest-ranking position where water quality was poorest. He sucked his trunk, as if uncertain how to negotiate his place in the hierarchy.

By now I had been in the tower two hours; it was nearly noon, and the day had turned hot and bleak. It had been a particularly dry year, so the trees were parched and the clearing especially stark. As Greg became more and more agitated, I could sense that nobody wanted to be in the presence of an angry don.

Finally the explanation strode in on four legs, his shoulders high and head up, clearly looking for trouble. It was the third-ranking bull, Kevin, the group bully who frequently sparred with the lower-ranking bulls. I could identify him by his wide-splayed tusks and bald tail. I could also see the tell-tale sign of urine dribbling from his penis sheath, and, judging from his posture and long stride, he appeared ready to take on Greg. Kevin was obviously in musth.

I had never witnessed a musth bull challenging a dominant bull, and as Kevin arrived at the water hole, I was on the edge of my seat. I suspected that Greg had been avoiding Kevin, and I fully expected Greg either to back down or to get the daylights beaten out of him. Everything I had read suggested that a rival in musth had the advantage in a fight with a top-ranking bull. Such confrontations have even been known to end in death.

Female elephants live much of their lives apart from males, in family groups led by a matriarch. A mother, grandmother and maybe even a great-grandmother live together with daughters, nieces, granddaughters and their offspring—on average, about 15 individuals. Young males leave the group when they are between 12 and 15 years old; the females stay together as long as they live, which can be up to 70 years. The matriarch, usually the oldest in the group, makes decisions about where and when to move and rest, on both a daily and seasonal basis.

Among female elephants, or cows, gestation lasts 22 months, and babies are weaned after two years, so estrous cycles are spaced from four to six years apart. Because of this long interval, relatively few female elephants are ovulating in any one season. Females are thought to advertise estrus through hormones secreted in their urine as well as through the repetition of a vocalization called an estrus rumble. Musth bulls also have a particular rumble that advertises their status to estrus females.

Only a few bulls go into musth at any one time. The prevailing theory is that this staggering of bulls’ musth allows lower-ranking males to gain a temporary advantage over higher-ranking ones by becoming so agitated that dominant bulls won’t want to take them on, even in the presence of a female ready to mate. This mechanism allows more males to mate, rather than just the don, which makes the population more genetically diverse.

Although females do not go into estrus at the same time, more of them tend to become fertile at the end of the rainy season, which allows them to give birth in the middle of another rainy season, when more food is available. Long-term studies in Amboseli indicate that dominant bulls tend to come into musth when a greater number of females are in estrus, and they maintain their musth longer than younger, less dominant bulls. But this was the dry season, and Greg exhibited no signs of musth.

At the water hole, Kevin swaggered up for a drink. The other bulls backed away like a crowd avoiding a street fight. Not Greg. He marched clear around the water with his head held high, back arched, straight toward Kevin. Kevin immediately started backing up.

I had never seen an animal back up so sure-footedly. Kevin kept his same even and wide gait, only in reverse.

After a retreat of about 50 yards, Kevin squared off to face his assailant. Greg puffed himself up and kicked dust in all directions. He lifted his head even higher and made a full frontal attack.

Two mighty heads collided in a dusty clash. Tusks met in an explosive crack, with trunks tucked under bellies to stay clear of the mighty blows. Greg held his ears out to the sides, with the top and bottom portions folded backward and the middle protruding—an extremely aggressive posture. And using the full weight of his body, he raised his head again and slammed Kevin with his tusks. Dust flew, with Kevin in full retreat.

I couldn’t believe it—a high-ranking bull in musth was getting his hide kicked. A musth bull was thought to rise to the top of the hierarchy and remain there until his testosterone levels returned to normal, perhaps as long as several months. What was going on?

But just when I thought Greg had won, Kevin dug in. With their heads only inches apart, the two bulls locked eyes and squared up again, muscles taut.

There were false starts, head thrusts from inches away and all manner of insults cast through foot tosses, stiff trunks and arched backs. These two seemed equally matched, and for a half-hour the fight was a stalemate.

Then Kevin lowered his head. Greg seized the moment. He dragged his own trunk on the ground and stamped purposefully forward, lunging at Kevin until the lesser bull was finally able to maneuver behind a concrete bunker we use for ground-level observations.

Feet stamping in a sideways dance, thrusting their jaws out at each other, the two bulls faced each other across the bunker. Greg tossed his trunk across the nine-foot divide in what appeared to be frustration. At last he was able to break the standoff, catching Kevin in a sideways attack and getting him out in the open.

Kevin retreated a few paces, then turned and walked out of the clearing, defeated.

I was blown away by what I had just witnessed. A high-ranking bull in musth was supposed to be invincible. Were the rules of musth different for bulls that have spent most of their time in a close social group? Kevin hadn’t frightened Greg; if anything, Kevin’s musth appeared to fuel Greg’s aggression. Greg, I realized, would simply not tolerate a usurpation of his power.

My mind raced over the possible explanations. Had Etosha’s arid environment created a different social atmosphere than Amboseli’s, where similar conflicts had had the opposite outcome? Perhaps water scarcity influenced social structure—even the dynamics of musth.

Could it be that the don had an influence over the other males’ hormones? This phenomenon is well documented in the primate world. And in two instances in South Africa, when older bulls had been reintroduced to a territory, younger bulls had then cycled out of musth. Did a bull have to leave his group to go into musth? This episode with Kevin made me think that just might be the case. And that would explain why musth bulls are usually alone while they search for females.

When the dust settled, some of the lower-ranking bulls still seemed agitated. The boys’ club never really returned to normal for the rest of the day.

In the early afternoon, Greg determined it was time to leave. He set the trajectory, leaning forward and laying his trunk on the ground—as if gathering information to inform his decision. He remained frozen in that position for more than a minute before pointing his body in a new direction.

When Greg finally decided to head west, he flapped his ears and emitted a long, barely audible low-frequency call that has been described as a “let’s go” rumble. This was met with ear flapping and low rumbles from several other bulls. On some days, I’d seen him give a shove of encouragement to a younger bull reluctant to line up and leave the water hole. This time, it was Keith who was balking; Greg put his head against Keith’s rear and pushed. The bulls finished drinking and headed out in a long line, Greg in the lead.

Dominance among female elephants means leading. The matriarch decides where the group should go and when. Dominance in bulls has been thought to be different, a temporary measure of who could stay on top of the heap, who could physically overpower the other members of the group and mate with the most females. It isn’t about caring whether the group sticks together. But dominance seemed to mean something more complicated to these bulls. I began to wonder whether I was witnessing not just dominance but something that might be called leadership. Greg certainly appeared to be rounding up the group and leading his bulls to another carefully selected venue.

As I watched the boys’ club disappear in a long chalky line into the trees, I wondered if paying respects to the don went beyond maintaining the pecking order. I felt a little crazy even thinking it, but these bull elephants, who weren’t necessarily related, were behaving like family.

A few seasons have passed since that afternoon at Etosha.This past summer Greg developed a gaping hole near the tip of his trunk—probably an abscess. It caused him to spill water as he drank. He appeared to have lost a lot of weight, and he spent a lot of time soaking his wound after drinking. He seemed extremely grumpy, casting off friendly overtures with a crack of his ears. It looked like he didn’t want company.

Yet on occasion he still came to the water hole with his younger contingent: Keith, Tim and Spencer, as well as some new recruits, Little Donnie and Little Richie. The newcomers made me wonder if Greg might pull through this rough patch. The youngsters were fresh out of their matriarchal families and looking for company, and they seemed eager to be by Greg’s side. Despite his crabby mood, Greg seemed to still know how to attract young constituents—those that might be there for him during conflicts with challengers who aren’t in musth.

As we were packing up to leave for the season, Greg lumbered in for one of his long drinking sessions—his new recruits in tow. The younger bulls had long since left the area by the time Greg had finished soaking his trunk and was ready to depart. Despite being alone, he initiated his ritual rumbling as he left—his long, low calls unanswered—as if engaging in an old habit that wouldn’t die.

It was a haunting scene. I stopped and watched through my night vision scope. I couldn’t help but feel sorry for him as he stood at the edge of the clearing. What was he waiting for?

Later, I got my answer. I heard rumbles in the distance—two bulls vocalizing. When I looked through my night vision scope again, I saw that Greg was with Keith. Perhaps Keith, having had his drink hours earlier, had returned to collect him.

Greg and Keith walked out together, each in turn rumbling and flapping his ears. They lumbered up a path and out of sight.

I felt relieved.

Caitlin O’Connell-Rodwell is an ecologist at Stanford University and the author of The Elephant’s Secret Sense. Susan McConnell is a neurobiologist at Stanford.