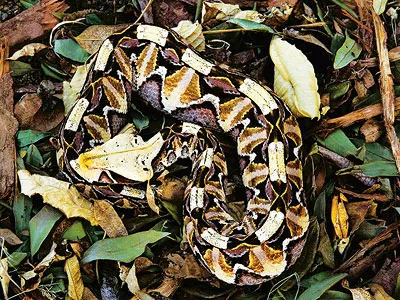

Hiding in Plain Sight

A veteran photographer shows the extraordinary knack that some animals have for…disappearing

The wildlife photographs that make us ooh and aah usually depict dramatic action. A lion digs its teeth into a zebra's neck, buffxaloes stampede through a cloud of dust, a pair of cranes strut out a mating dance&151;we like our animals highlighted at their most furious, frightened or amorous.

That's rarely how they appear in nature, of course. Most of the time, they’re just trying to blend in. Photographer Art Wolfe, 53, has more than 60 books and plenty of wildlife action shots to his name, but in a new book, Vanishing Act, he defies conventions to show what he calls "animals' incredible ability to vanish in plain sight." In these photographs (taken in Kenya, South Africa, Panama, Malaysia and 21 other nations), the animals typically appear in the corner of the frame rather than the center, and some are partly obscured by plants. He further helps the subjects get lost by making both the foreground and background sharp. “Basically, I’m teasing the audience,” he says.

Ever since people thousands of years ago noted the uncanny trickery of animal camouflage, nature watchers have taken pains to understand it. Some animals’ color matches their favored habitat: plovers that feed in wet sand and muck have darker-brown backs than plover species that spend their time in dry, lighter-colored sand dunes. Some animals coordinate their look with the seasons, shedding dark fur or molting dark feathers once the snow flies. Certain sea creatures tint their skin with pigments from the corals they’ve eaten to take on the color of their home reef.

Somewhat counterintuitively, vivid splotches or stripes help protect animals such as zebras and giraffes. Stripes can distract a lion—which is susceptible to visual illusions like the one we experience when we can’t decide whether a picture shows a vase or two faces—from recognizing the outline of the zebra’s body. (What works for animals works for people too. Military camouflage, first introduced in World War I, was inspired by research on animal camouflage.)

Mimicry is the shrewdest disguise. Mantises, shaped like flowers, devour insects that fly in to pollinate mock blossoms. A copperhead twitches the tip of its worm-like tail to lure hungry frogs. And tasty viceroy butterflies are safe from birds because they resemble monarchs, which are unpalatable.

Some camouflage works in concert with particular behaviors. When a bittern, a marsh bird, is startled, it sticks its long neck and bill straight up and displays its vertically striped feathers, looking for all the world like a patch of reeds. Just this year, scientists reported that an octopus that lives in the Pacific Ocean off Australia walks along the seafloor with two arms, gently waving the other six so that it resembles a rolling clump of algae.

The modern study of camouflage began shortly after Charles Darwin proposed, in 1858, that new species arise through evolution by natural selection. He recognized that there are variations among individual members of a species, with some individuals being stronger or faster or better camouflaged. If an inherited trait helps an individual survive in a given environment, and reproduce, the trait will be passed on to future generations. If enough new traits accumulate in a group over time, a new species emerges.

Some of the first experimental evidence for Darwinian evolution came from research on camouflage, which is an easily studied adaptation—a trait that makes an animal more fit to survive in a particular habitat. Nearly a century ago, scientists dropped house mice into enclosures of various colors and found that owls snatched fewer mice from backgrounds that matched mouse fur. Likewise, researchers put mosquitofish in light or dark containers, waited for the fish to acquire light or dark coloration, then put them into different-colored containers overseen by hungry penguins. Fish that blended in fared better, while those that stood out were better fare.

Those experiments and others helped demystify evolution by vividly demonstrating how predators do its work, naturally selecting which mice or fish or other living thing survives in which environment. Thousands of studies have bolstered Darwin’s revolutionary discovery. Today, researchers are identifying particular gene sequences that can make an animal inconspicuous. But even now, one of the best ways to appreciate evolution is to notice how well camouflage tricks your own eye.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)