Healers Once Prescribed Chocolate Like Aspirin

From ancient Mesoamerica to Renaissance Europe, the modern confectionary treat has medical roots

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/6a/186acab5-f0d1-4e31-93da-f8109859c280/nutelladrug.jpg)

Chocolate—it makes miracle pills go down easier. Miracle Max probably wasn't thinking of the Aztecs when he used a chocolate-coated pill to revive Westley in The Princess Bride. But chocolate has been used in medicine since at least the 1500s, and probably much earlier, as part of Olmec, Maya and Aztec treatments for a range of ailments.

“Throughout history, chocolate is considered to be extremely healthful,” says Louis Grivetti, a nutrition historian at the University of California, Davis.

Most of what we know about how pre-colonial healers prescribed cacao comes from European sources. According to the Florentine Codex, compiled by a priest named Bernardino de Sahagún in 1590, the Aztecs brewed a drink from cacao and silk cotton tree bark (Castilla elastica) to treat infections. Children suffering from diarrhea received a drink made from the grounds of five cacao beans mixed with unidentified plant roots. Another recipe incorporated cacao into a cough treatment. Written in 1552, the Badianus Manuscript lists a host of ailments cacao-based remedies could treat, including angina, fatigue, dysentery, gout, hemorrhoids and even dental problems. There’s also Montezuma’s fabled use of chocolate concoctions before visiting his wives.

Long before Mary Poppins and her spoonful of sugar, the Aztecs used cacao to mask the unsavory flavors of other medicinal ingredients, including roots used to treat fever and “giants bones”—possibly mistaken vertebrate fossils—used to treat blood in the urine. A manuscript of Maya curative chants mentions that after chanting, patients consumed a cacao-based concoction to treat skin rashes, fever and seizures.

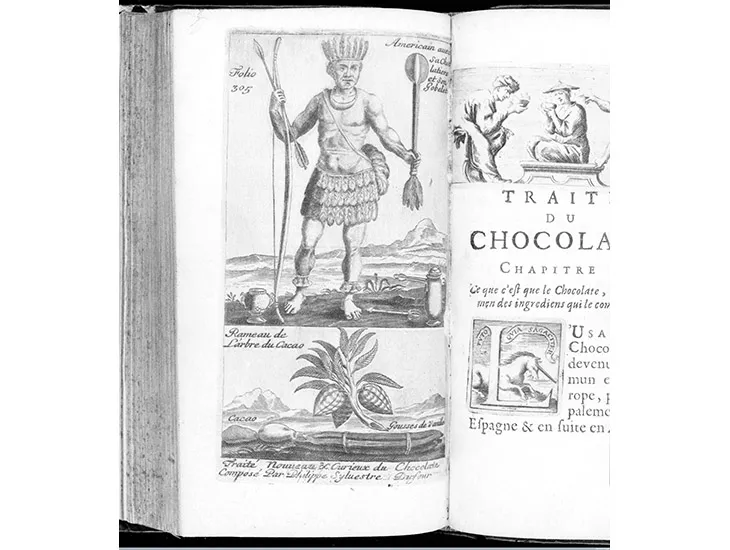

Maya dignitaries introduced chocolate to Spain in 1552, and from there it spread across the continent. Europeans embraced the exotic delicacy and started mixing in some flavor enhancers, such as cinnamon and vanilla. Not long after chocolate was imported as a food, it gained a reputation as a drug. At this point, European medicine still drew heavily from classical scholars Hippocrates and Galen. Four “humors” comprised the human body, and whenever these humors fell out of balance, disease ensued. Diseases could be “hot” or “cold”, “wet” or “dry”, and physicians treated them with oppositely classified pharmaceuticals. Though cold by nature, cacao could supposedly be prepared in hot or cold forms, depending on necessity.

While some may have viewed chocolate as a miracle drug or cure-all, others saw it as a treatment for specific illnesses. In the late 1500s and 1600s, Western doctors experimented with chocolate as a treatment for many of the same conditions it had been used for in the Americas, including chest pain, fevers, stomach problems, kidney issues and fatigue.

In a 1631 treatise, Spanish physician Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma gave a glowing description of the medicinal food: “It quite takes away the Morpheus, cleaneth the teeth, and sweeteneth the breath, provokes urine, cures the stone, and expels poison, and preserves from all infectious diseases.”

Several scholars noted the potential for chocolate eaters to gain weight, citing potential for emaciated or convalescing patients. In the 1700s, some doctors incorporated chocolate into smallpox treatments as a way to prevent the weight loss associated with the disease. Richard Saunders (a pen name for Benjamin Franklin) references the benefits of chocolate against smallpox in the 1761 edition of Poor Richard’s Almanac. During the U.S. Civil War, injured soldiers were given chocolate when available, presumably to help keep their energy up and again help them gain weight.

Like the Aztecs, European doctors used chocolate to help deliver drugs—some less savory than others. Eighteenth century Frenchman D. de Quélus posited that chocolate could be used as a vehicle for “powders of millipedes, earthworms, vipers and the livers and galls of eels.”

As they experimented, European doctors clearly got a little creative in their chocolate prescriptions. In 1796, one scholar argued that chocolate could delay the growth of white hair. In 1864, Auguste Debay described a chocolate concoction used to treat syphilis. Chocolate was also cited as a part of a treatment regimen for a measles outbreak in 19th-century Mexico. “These are hunches. They’re schemes to get people to buy the product,” says Grivetti.

With such a wide range of ailments and recipes, would any of these chocolate medicines actually have worked? Maybe. Grivetti thinks that the perceived general health benefit of chocolate may have stemmed from its preparation. In many cases, chocolate concoctions were heated, sometimes boiled, before drinking. By simply heating the liquid, both Mesoamerican and early European drinkers may have unknowingly killed microbial pathogens.

“It’s probably more serendipitous than anything,” says Grivetti. Without a time machine and a water testing kit, there’s no way to know for sure. As for the nutritional content of cacao itself, several studies have suggested that the flavanoid compounds common in unprocessed dark chocolate may reduce risks from clogged arteries and increase circulation to the hands and feet. Unfortunately, since the mid-1800s, dutching has removed dark chocolate’s acidity—and its flavanoids. Around the same time, people were starting to add cocoa butter back into processed chocolate to make bars, along with the dairy and sugar that are now common in modern chocolate candy. These manufacturing methods probably make chocolate more of a medical hindrance than help.

Chocolate prepared by the Aztecs and earlier Europeans would not have undergone dutching, so it might have benefitted heart health, possibly eased chest pain. The high calorie count of even early forms of chocolate also means it could have benefited patients fighting draining diseases like smallpox, but without knowledge of doses and a full understanding of how chocolate compounds work in the body, it’s hard to pin down the degree of benefit.

Though the overall health benefits of modern chocolate remain up for debate, a 2006 study found that eating a little chocolate could have a similar effect to taking an aspirin, and the chocolate compound theobromine has been marketed as an alternative to the erectile dysfunction drug Viagra.

So whether you're mostly dead or merely aching, there's a chance that a little chocolate could give your health a boost. Using it to cure syphilis, however—that would take a miracle.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)