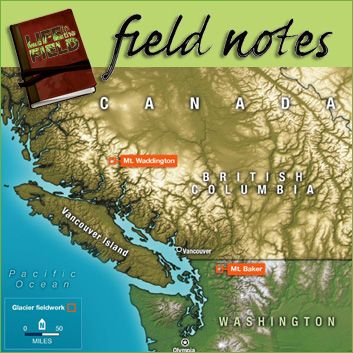

Glaciologist Erin Pettit Reports from the Field

Tuesday July 17, 2006: Day Four on Mount Waddington

My day started at about 7 a.m., well before everyone else's. I crawled out of my sleeping bag and into my clothes. Layering clothes is critical here because you can cool off quickly at night or when a cloud comes by, but the sun can roast you during midday and it is important not to sweat—the easiest way to get hypothermia. I headed over to the cook tent nestled in snow, a dome with just enough room for the five of us on our team to sit and still have space to make a meal. I boiled some water and made myself some tea and oatmeal.

I kind of enjoyed having the mountain to myself in the morning. Doug, Eric, Jeff and Bella worked until 5 a.m. drilling, taking advantage of the cold night air because the drill works better when the ice isn't melting. When we planned this project, we weren't sure how good the conditions would be for drilling and how well the ice at this site would preserve the climate history. We are used to drilling in Antarctica or Greenland, so we expected that the drill might have problems in the warmth of British Columbia. And it did. Our first day drilling we realized we would have to switch to a night schedule.

The night schedule worked well for the drilling, but I didn't like it because my part of this project—using GPS to measure the speed of the glacier and using ice-penetrating radar to look at the interior of the glacier—required me to work when it was light out to travel safely on the glacier. (This radar system sends an electrical pulse into the ice that reflects back and provides information on what is underneath us, somewhat similar to how ultrasound can image the interior of our bodies.) Today, my goal was more radar. Two days ago, we had observed with the radar system a strong reflective layer in the ice about 35 meters (115 feet) deep. We weren't sure what was in the ice to cause that layer: Was it a dust layer? A change in density? Debris from an old avalanche? Or the bottom of the glacier? I set out to see how widespread the layer was around the upper part of the glacier. The radar system took two people to operate. The "brain" of the radar system was set up on an orange, plastic kid's sled, while the antennae that send and receive the signals had to be picked up and moved three feet at a time to get a detailed image—slow traveling.

This morning I wanted to change the system to make it easier and faster to move around. By the time I was ready to get started, Eric and Doug appeared in the cook tent; they found that sleeping in the bright sun during the day is hard, no matter how late they went to bed. Eric offered to help me with the radar system. We quickly realized that the snow was firm enough that we could move the antennae faster simply by dragging them on a blue plastic tarp (high-tech science, of course). Once we figured this out, we set out to take measurements all around the safe (crevasse-free) areas of the upper part of the glacier. Although we kept constant watch on the system and the data we were collecting, this also gave us time to ski around and talk to each other. When the radar system ran out of batteries, around lunchtime, we headed back to camp to charge the batteries and analyze the data.

By then, everyone was awake, and we discussed the plan for the afternoon. Bella, our driller, said there were a few things she wanted to check on the drill to make sure it was working properly and Jeff, our undergraduate student, would help her. We also needed to radio Mike, the helicopter pilot, to arrange for him to pick up the boxes of ice core we had recovered so far and take them to the freezer truck waiting down at the helicopter hangar. We kept the ice core in insulated boxes and covered in snow, but it was warm enough up there that too much time in the sunshine would start to melt our ice, potentially making it unusable. Eric called Mike on the radio, and a plan was set for him to fly up at approximately 7 p.m. and drop off the net we needed to package up the ice cores. He would pick up Jeff and me and take us to Sunny Knob, where we needed to install a temporary GPS base station. Then he would return to take us back to camp, pick up the ice core boxes and head back to the hangar.

After lunch, I took a look at the radar data, which showed this mysterious layer across the whole glacier at about the same depth. This didn't explain everything, but at least it let us know that it probably wasn't old avalanche debris (an avalanche would leave more debris near the source and less or no debris far away from the source) and gave us a few more clues. We became quite excited to see what we would find when we reached that depth with the ice core drilling, which, if everything went well, would be that evening. When we had finished checking on the drill, analyzing the data and putting the radar away for the day, we all went to take naps in our tents to prepare for another long night of drilling.

I was the first to wake up, around 5 p.m., and started preparing dinner. By 6 p.m, everyone was awake and ready to eat. For dessert, Eric brought out a few cans of mandarin oranges as a tribute to Canadian alpine explorers Phyllis and Don Munday, who were the first to attempt to climb to the top of Mount Waddington in 1928. Phyllis had carried mandarin oranges as a treat to help the team's morale during the challenging parts of the climb.

As planned, Mike showed up at 7 p.m. Jeff and I climbed into the helicopter with the equipment we needed and a backpack full of emergency gear in case the weather turned bad and we were stuck at Sunny Knob all night (or even for several days). Eric needed to tell Mike something, but there was some confusion, and with the noise of the helicopter and before we all knew what was happening, we took off and Eric was still with us. The amusing thing about it was that Doug and Bella didn't notice Eric was gone for a long time (they thought he was in our toilet tent or in his sleep tent).

After a five-minute flight down the glacier, Mike dropped Jeff and me off at Sunny Knob, where it was indeed sunny. Eric stayed in the helicopter and flew with Mike to pick up some climbers from another site. We spent about 15 minutes setting up the GPS base station, and then we explored and took photos for an hour, waiting for the helicopter to return. The heather was in bloom, and other alpine plants were abundant, and it was nice to be on solid ground after spending days walking on the snow. We had a beautiful view of the whole valley, which was filled with the Teidemann Glacier, as well as some beautiful peaks around us. We took many photos and enjoyed the moment of green before heading back to the white.

We were a bit sad when Mike returned to pick us up; we decided we needed several days at Sunny Knob to really be able to explore the area. But we had drilling to do. We arrived back at camp close to 9 p.m. Doug and Bella had the ice core boxes in the net ready to fly home as a sling load because they wouldn't fit inside the helicopter. In order to attach the sling, Eric stood on the snow near the boxes and Mike maneuvered the helicopter down on top of him so that he could hook the cable to the bottom of the helicopter. Mike is a great pilot, but that doesn't keep us from being nervous when our precious ice core samples are swinging around underneath the helicopter!

By the time the helicopter took off, the sun was setting, and Bella was finishing up the preparations to start that night's drilling. We really didn't need all five of us to do the drilling–three or maybe four was plenty–but it was a beautiful night and we were just having a good time working, laughing and listening to music.

The drilling went smoothly. Bella lowered the drill into the nearly 20-meter (65-feet)-deep hole and drilled down until she had cut one meter (three feet) of core. Then she broke the core and brought the drill back up with the section of the ice core inside the barrel of the drill. Once the drill was out of the hole, Eric detached the barrel from the drill rig and laid it on its side in the snow. Then Eric gently pushed one end of the ice core section with a long pole until it came out the other end of the barrel to where Doug and I were waiting for it. We were deep enough that the core was solid ice, so it was pretty strong. But we still had to be very careful not to let it slip out of our hands. We laid it carefully on a piece of plastic. Doug measured its length and made note of any unusual layers. I drilled a small hole in the core and placed a thermometer inside it to measure the ice temperature. Meanwhile, Eric and Bella put the drill back together, and she began to lower it down the hole again. Finally, Doug and I packaged up the core in a long, skinny, plastic bag, tagged it with identifying marks and put it in a labeled cardboard tube. Then Jeff put the tube into an insulated core box. The whole process took 10 to 15 minutes, by which time Bella brought up the next core.

If everything is working well, then a rhythm emerges and we can work smoothly for several hours. We have to make sure that everyone stays warm, however, because kneeling in the snow and working with ice can make for cold knees and hands. We often take breaks for a hot drink and some food.

Still not on the nighttime schedule the others were, I had to go to bed around 11 p.m. I awoke at about 2:30 or 3 a.m to some talking and commotion. In a sleepy daze, I fell back to sleep. When I woke in the morning, I found Eric eager to tell me the news of the night. They had indeed reached the bright layer we had seen with the radar: they had brought up a layer of ice that was so warm it was dripping wet—not at all what we expected. This meant a change of plans for the next couple of days. We had to switch to using a drill cutter that could handle wet ice (one that cut by melting the ice rather than with a sharp edge). And we were back to working the day shift. But before we did anything, we wanted to send my video camera down the borehole to see what was really at the bottom of the hole: How wet was it? Was there dirt down there too? Knowing this would help us plan for the next stage of drilling.