Foot Fluids Work in Surprising Ways to Help Insects Stick to Walls

Long though to boost bug stickiness, the fluid may instead help insects mold to contours and make quick exits

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/89/b9893a30-0a12-43ca-af5d-ac361bcc655c/janfeb2016_o05_phenom.jpg)

As soon as microscopes debuted in the 17th century, scientists zoomed in on the feet of common houseflies, marveling at the tiny “soles” that enable insects to scale windowpanes and walk upside down on ceilings. “People were looking for some magic mechanism,” says University of Cambridge zoologist David Labonte.

More than 300 years later, they’re still looking. The minuscule scale and complex geometry of insect feet, not to mention the unruly nature of six-legged research subjects, has meant that when it comes to insect podiatry, says Labonte, “you’d be surprised how much we don’t know.”

But he and his colleagues think they’re creeping closer to some answers.

Scientists have long noticed that insects have wet feet: They leave damp little footprints on flower petals, for instance. (The amount of liquid, an oily hydrocarbon, is minute: around a quadrillionth of a liter per footprint.) It had previously been suspected that the liquid helps glue insects to vertical surfaces through capillary and viscous forces, much as a thin layer of water helps a wet beer glass stick to a tabletop.

To test this hypothesis, Labonte decided to use—what else?—Indian stick insects. It was not their fitting name but their lackadaisical attitude that attracted him. The bugs, having evolved to resemble twigs, are mostly motionless, and they have the happy habit of extending their front feet, which allowed Labonte to attach wires to their protruding tootsies. With a fiber-optic sensor, he measured how much force it took to lift a foot—at different degrees of wetness—from glass plates at varying speeds.

“I’m not sure if they were even awake during all this,” Labonte says of his “stickies.”Labonte learned that the secretion isn’t an adhesive after all, at least not in the predicted manner: Wet and dry feet performed about the same. In fact, Labonte now thinks that the fluid may have the opposite effect, allowing insects to rapidly unstick their feet, by providing a slippery “release layer.” The moisture may even keep insect foot pads supple, and better able to mold to microscopic contours of ceilings and walls, helping them stick in a previously unanticipated way.

Testing this idea over the next year will involve constructing a millimeter-size rubber model of a bug foot that Labonte can manipulate without worrying about five other flailing feet. Grasping bio-adhesive principles may also inspire advances in manufacturing, like ultra-dexterous robots that can handle and precisely place tiny parts. (Damp sponges, like moist insect feet, could help robots release their grip.) So far the dream of a ready-wear Spiderman suit has less academic traction, but some scientists cling to it nonetheless.

Related Reads

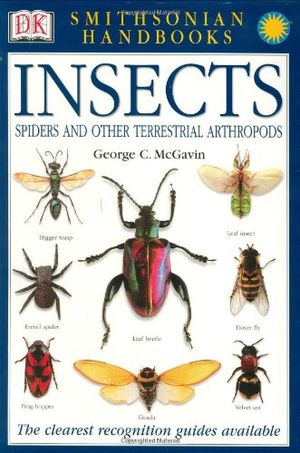

Insects (Smithsonian Handbooks)