Fifty Years of Arctic National Wildlife Preservation

Biologist George Schaller on the debate over ANWR conservation and why the refuge must be saved

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ANWR-polar-bear-cub-631.jpg)

This winter marks the 50th anniversary of the designation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), a 19-million-acre refuge in Alaska that runs for 190 miles along the state’s eastern border with Canada before meeting the Arctic’s Beaufort Sea. The refuge is home to one the United States’ most contentious conservation battles, over a region known as the 1002 Area.

Making up less than 8 percent of the refuge, the 1002 Area contains vital habitat for an international cast of migratory birds and other animals, like polar bears, that rely on the border of terrestrial and marine ecosystems. At the root of the controversy is the fact that the section of coastal plain hosts not only the preferred calving ground for a large, migratory population of caribou, but also, according to U.S. Geological Survey estimates, 7.7 billion barrels of oil and 3.5 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. Today, the battle continues over the 1002 Area, which could be opened to drilling by an act of Congress.

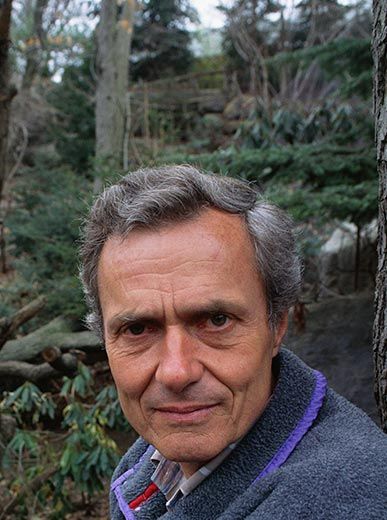

As a graduate student, George Schaller accompanied the naturalists Olaus and Mardy Murie on an expedition into ANWR’s Brooks Range. Many regard that 1956 trip as laying the scientific groundwork for the establishment of the refuge. Today, Schaller, 77, is a senior conservation scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society and vice president of Panthera, a big-cat conservation agency. He is widely regarded as one of the world’s preeminent conservation biologists. Schaller has traveled the world to do pioneering research on wildlife, and he has worked to create national parks in places like China, Nepal and Brazil, and a peace park spanning four countries in Central Asia. But the Arctic is never far from his thoughts.

Why are people still talking about the Muries’ 1956 Brooks Range expedition?

The Muries were extremely good advocates for the refuge because they came back from their expedition with solid information about the natural history of the area. Momentum had been building since the late 1930s to protect the area, but this was the first such detailed scientific effort to describe the diversity of life there.

After the expedition, the Muries, with the help of the Wilderness Society, were able to ignite a major cooperative effort between Alaskans, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Park Service, Interior Secretary Fred Seaton and even the late Senator Ted Stevens, though he became a big foe once there was oil.

Did your time working in the Arctic with the Muries shape your ideas about science and conservation?

It was an illuminating experience for me, which has stayed with me my whole life. Yes, we were doing science, but facts don’t mean very much unless you put them into context. Olaus’ context, which he talked about often, was that the Arctic must be protected and we have to fight to see this done. We have to consider not just the science but the beauty, ethical and spiritual values of the area—“the precious intangible values.” That combination of science and advocacy most definitely has shaped what I have done over the past half century.

From a biological standpoint, is there anything that makes ANWR more critical to protect than other areas in the Alaskan Arctic?

The refuge is large—about 31,000 square miles—and that is of great importance to its future. The other important aspect is that it has all of the major habitats—taiga forest, scrublands, alpine meadows, glaciers, tundra and, of course, life doesn’t stop at the edge of the land but extends into the Beaufort Sea, which, unfortunately, the refuge does not include.

Why is its size so crucial?

Size is important because with climate change the vegetation zones will shift. By being large and varied in topography, plant and animal life can shift with its habitat. The refuge provides a place for species to adapt and still be within a protected area.

In addition, unlike so many other areas in the Arctic, humans have not modified the refuge. It retains its ecological wholeness. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has done a good job of maintaining it. Because its habitat remains unmodified, ANWR offers an essential baseline for comparison with changes elsewhere—for example, the changes associated with climate change.

The refuge is often referred to as “the Last Great Wilderness.” Is it truly “wilderness?”

It is indeed America’s last great wilderness, something the nation should be proud to protect as part of its natural heritage. However, we tend to think of places with few or no people such as the Arctic Refuge as “wilderness.” I do too, from my cultural perspective. Remember, if you’re a Gwich’in or Inuit, the Arctic Refuge and other parts of the Brooks Range is your home in which you subsist. It has symbolic value too, but in a much more specific way in that there are sacred places and special symbolic sites. They may view their “wilderness” quite differently.

The National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, to the west, is four million acres larger than ANWR. What is the difference between the two?

The NPR-A is not an undeveloped place. Part of the Bureau of Land Management’s mandate is to allow development—there’s been drilling, exploration and much has already been leased. Unlike the refuge, it also does not extend over the Brooks Range south into extensive taiga.

Are there unsolved mysteries left in the Arctic?

We know very little about the ecological processes in the Arctic, or anywhere else for that matter. Yes, somebody like myself studies a species but that’s one of thousands that are all integrated with each other. How are they all integrated to form a functioning ecological community? With climate change, we don’t even know the ecological base line that we’re dealing with. What will happen to the tundra vegetation when the permafrost melts? We really need to know far more. But fortunately a considerable amount of research is now going on.

It has been over 50 years. Why do you keep fighting to protect ANWR?

If you treasure something, you can never turn your back, or the proponents of plunder and pollution will move in and destroy it. Let us hope that this anniversary can stimulate politicians to act with patriotism and social responsibility by designating the coastal plain of the Arctic refuge as a wilderness area, and thereby forever prevent oil and gas companies and other development from destroying the heart of American’s last great wilderness.