Do Our Brains Find Certain Shapes More Attractive Than Others?

A new exhibition in Washington, D.C., claims that humans have an affinity for curves—and there is scientific data to prove it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Collage-brain-shapes.jpg)

A century ago, a British art critic by the name of Clive Bell attempted to explain what makes art, well, art. He postulated that there is a “significant form”—a distinct set of lines, colors, textures and shapes—that qualifies a given work as art. These aesthetic qualities trigger a pleasing response in the viewer. And, that response, he argued, is universal, no matter where or when that viewer lives.

In 2010, neuroscientists at the Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute at Johns Hopkins University joined forces with the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore to conduct an experiment. What shapes are most pleasing, the group wondered, and what exactly is happening in our brains when we look at them? They had three hypotheses. It is possible, they thought, that the shapes we most prefer are more visually exciting, meaning that they spark intense brain activity. At the same time, it could be that our favorite shapes are serene and calm brain activity. Or, they surmised we very well might gravitate to shapes that spur a pattern of alternating strong and weak activity.

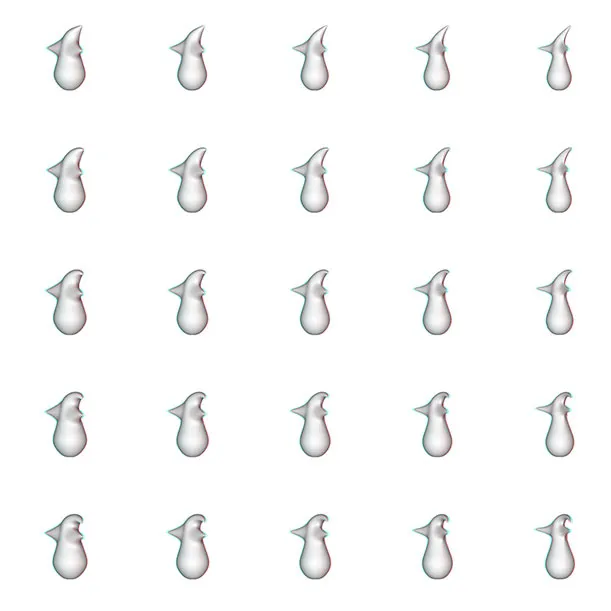

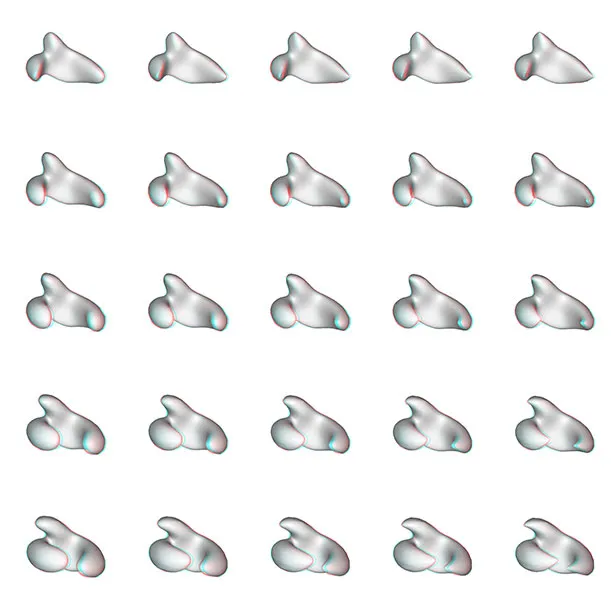

To investigate, the scientists created ten sets of images, which they hung on a wall at the Walters Art Museum in 2010. Each set included 25 shapes, all variations on a laser scan of a sculpture by artist Jean Arp. Arp’s work was chosen, in this case, because his sculptures are abstract forms that are not meant to represent any recognizable objects. Upon entering the exhibition, called “Beauty and the Brain,” visitors put on a pair of 3D glasses and then, for each image set, noted the their “most preferred” and “least preferred” shape on a ballot. The shapes were basically blobs with various appendages. The neuroscientists then reviewed the museum-goers’ responses in conjunction with fMRI scans taken on lab study participants looking at the very same images.

“We wanted to be rigorous about it, quantitative, that is, try to really understand what kind of information neurons are encoding and…why some things would seem more pleasing or preferable to human observers than other things. I have found it to be almost universally true in data and also in audiences that the vast majority have a specific set of preferences,” says Charles E. Connor, director of the Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute.

“Beauty and the Brain Revealed,” an exhibition now on display at the AAAS Art Gallery in Washington, D.C., allows others to participate in the exercise, while also reporting the original experiment’s results. Ultimately, the scientists found that visitors like shapes with gentle curves as opposed to sharp points. And, the magnetic brain imaging scans of the lab participants prove the team’s first hypothesis to be true: these preferred shapes produce stronger responses and increased activity in the brain.

As Johns Hopkins Magazine so eloquently put it, “Beauty is in the brain of the beholder.”

Now, you might expect, as the neuroscientists did, that sharp objects incite more of a reaction, given that they can signal danger. But the exhibition offers up some pretty sound reasoning for why the opposite may be true.

“One could speculate that the way we perceive sculpture relates to how the human brain is adapted for optimal information processing in the natural world,” reads the display. “Shallow convex surface curvature is characteristic of living organisms, because it is naturally produced by the fluid pressure of healthy tissue (e.g. muscle) against outer membranes (e.g. skin). The brain may have evolved to process information about such smoothly rounded shapes in order to guide survival behaviors like eating, mating and predator evasion. In contrast, the brain may devote less processing to high curvature, jagged forms, which tend to be inorganic (e.g. rocks) and thus less important.”

Another group of neuroscientists, this time at the University of Toronto at Scarborough, actually found similar results when looking at people’s preferences in architecture. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences earlier this year, they reported that test subjects shown 200 images—of rooms with round columns and oval ottomans and others with boxy couches and coffee tables—were much more likely to call the former “beautiful” than the latter. Brain scans taken while these participants were evaluating the interior designs showed that rounded decor prompted significantly more brain activity, much like what the Johns Hopkins group discovered.

“It’s worth noting this isn’t a men-love-curves thing: twice as many women as men took part in the study. Roundness seems to be a universal human pleasure,” writes Eric Jaffe on Co.Design.

Gary Vikan, former director of the Walters Art Museum and guest curator of the AAAS show, finds “Beauty and the Brain Revealed” to support Clive Bell’s postulation on significant form as a universal basis for art, as well as the idea professed by some in the field of neuroaesthetics that artists have an intuitive sense for neuroscience. Maybe, he claims, the best artists are those that tap into shapes that stimulate the viewer’s brain.

“Beauty and the Brain Revealed” is on display at the AAAS Art Gallery in Washington, D.C., through January 3, 2014.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)