Devastation From Above

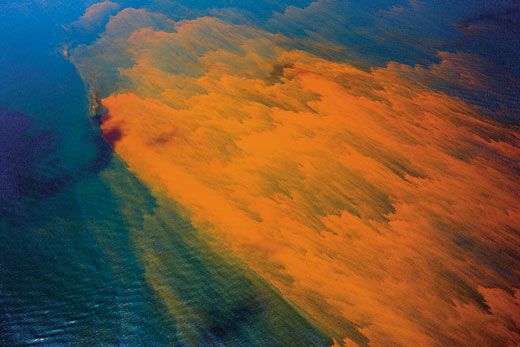

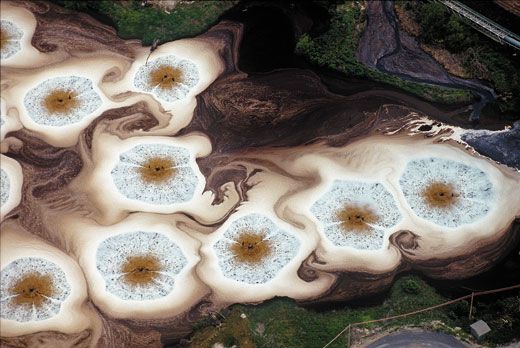

J. Henry Fair’s aerial photographs of industrial sites provoke a strange mix of admiration and concern

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Henry-Fair-Louisiana-power-plant-631.jpg)

J. Henry Fair was stumped. He couldn’t figure out how to photograph whatever might be hiding behind the walls and fences of industrial plants. Then, on a cross-country flight about 15 years ago, he looked out the window and saw a series of cooling towers poking through a low-lying fog. “Just get a plane!” he recalls thinking.

Today Fair, 51, is known in ecological as well as art circles for his strangely beautiful photographs of environmental degradation, most of them made out the open windows of small airplanes at about 1,000 feet. Fair has flown over oil refineries in Texas, paper mills in Ontario, ravaged West Virginia mountaintops, the oil-slicked Gulf of Mexico and a string of factories along the lower Mississippi River known as “Cancer Alley.” He is currently photographing coal ash disposal sites, many considered highly hazardous by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Dozens of his photographs appear in The Day After Tomorrow, due out next month. They don’t instantly make someone an environmentalist, says Lily Downing Burke, director of Manhattan’s Gerald Peters Gallery, which exhibits Fair’s work. “You have to think about them for a while. Then, when you find out what [the subject] is, it makes you take a step back and really question what we’re doing out there.”

Fair, who lives in New York State, consults scientists to better understand the images in his viewfinder: vast cranberry red ponds of hazardous bauxite waste spewed by aluminum smelters; kelly green pits filled with byproducts, some radioactive, from the manufacture of fertilizer. But pollution never looked so good. “To make an image that stops people it has to be something that tickles that beauty perception and makes people appreciate the aesthetics,” says Fair, who specialized in portraiture before taking to the skies.

His goal is not to indict—he doesn’t identify the polluters by name—but to raise public awareness about the costs of our choices. Such advocacy groups as Greenpeace and Rainforest Alliance have used Fair’s work to advance their causes.

“He is a real asset to the national environmental movement,” says Allen Hershkowitz, a senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council who contributed an essay to Fair’s book. A Fair photograph, he adds, “takes the viewer, in an artistic context, to an intellectual place that he or she didn’t expect to go. My aluminum foil comes from that? My electricity comes from that? My toilet paper comes from that?”

Critics say Fair’s bird’s-eye images tell only part of the story. Patrick Michaels, a senior environmental studies fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., says many people may tolerate, say, drilling natural gas wells in a forest—Fair has photographed these in the Catskill Mountains—if it reduces U.S. dependence on foreign oil.

Fair picked up his first camera, a Kodak Retina, at age 14, and learned darkroom techniques as a teenager working in a camera store in Charleston, South Carolina. His first subjects were people he would see on the streets and rusty machinery that he felt captured society in decay. At Fordham University in New York City, Fair ran the school’s photo labs while earning a degree in media studies; he graduated in 1983. He worked construction jobs until he could support himself with commercial photography, which included album covers for cellist Yo-Yo Ma and mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli. But as Fair’s eco-consciousness rose in the 1990s, his gaze turned back to machinery, industry and pollution.

Years of documenting “industrial scars” has had a personal effect. Fair says he uses as little electricity as possible and often burns candles to light his house. He tweets advice on living the environmentally aware life. (Example: bring your own bathrobe to the doctor’s office.)Though he owns a hybrid car, he often hitchhikes to a train station miles away. “People first think I’m crazy,” Fair says, “then they think about it a little bit.” Which is precisely the point.

Megan Gambino wrote about the aerial photos of David Maisel in January 2008.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)