Charging Ahead With a New Electric Car

An entrepreneur hits the road with a new approach for an all-electric car that overcomes its biggest shortcoming

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Shai-Agassi-Tel-Aviv-631.jpg)

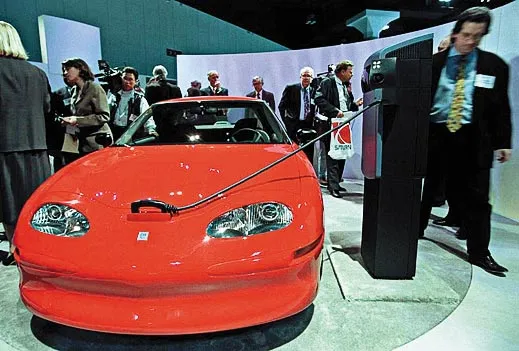

In the middle of 2007, Shai Agassi, a software multimillionaire turned environmental entrepreneur, was pondering how to make an electric car affordable to the average Joe. At that point, the all-electric vehicle—as opposed to electric-gasoline hybrids such as the Toyota Prius—was widely derided as impractical. General Motor’s EV1 had appeared in 1996 and, despite its cultlike following, the company stopped producing it after three years, saying the program was not commercially successful. The most advanced electric vehicle, the Tesla Roadster, was about to be released; it would travel some 200 miles on a fully charged battery, but at $109,000, the sleek sports car would be accessible only to the affluent; the company says about 1,200 of the vehicles are on the road. More affordable cars, at the time mostly in the planning stages, would be equipped with batteries averaging just 40 to 100 miles per charge. The power limitations had even spawned a new expression—“range anxiety,” the fear of being stranded with a dead battery miles from one’s destination.

Then, on a scouting trip to Tesla’s northern California plant, Agassi had an epiphany: “I scribbled down on a piece of paper, ‘batteries consumable. They’re like oil, not part of the car.’ That’s when it dawned on me—let’s make the batteries switchable.”

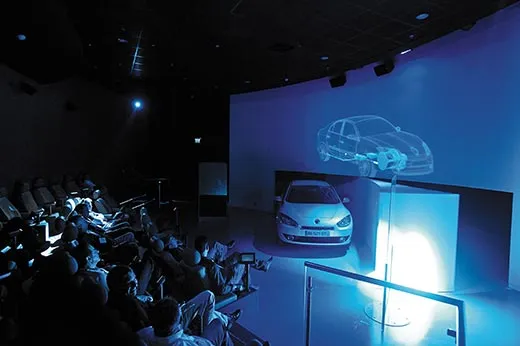

Two years later, in a cramped booth behind the exhibition hall at the Frankfurt Auto Show, Agassi was celebrating the payoff of that epiphany. The California company he founded, Better Place, had just announced its biggest deal yet: an agreement with Renault, the French car manufacturer, to produce 100,000 all-electric vehicles, or EVs, for sale in Israel and Denmark starting in 2010. Around the corner at the giant Renault exhibition, a garishly lit display showed a stylized version of one of Agassi’s “switching” stations in action: a robot with a steel claw extracted and replaced a model of a 600-pound battery from a cavity in the bottom of the vehicle in three minutes.

“We use the same technology that F-16 fighters use to load their bombs,” said Agassi, an Israeli-American, who got the inspiration from a pilot in the Israel Defense Forces.

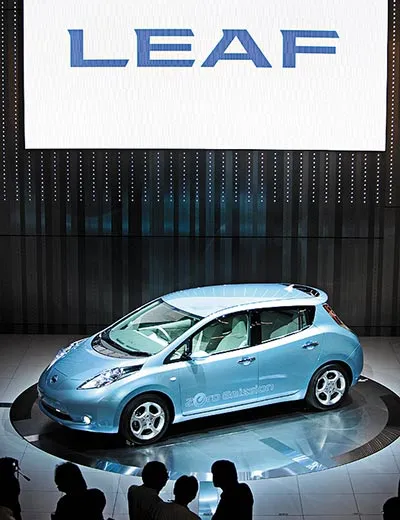

If Agassi’s dream once seemed premature, concern about global warming, government pressure to produce zero-emissions vehicles, high oil prices and rapid improvements in lithium-ion batteries have begun to make electric vehicles look increasingly viable. By 2013, several models will have hit the road, including the Smart Fortwo, made by Daimler; the Nissan Leaf; the Mitsubishi i-MiEV; the Chevrolet Volt; and Tesla’s Model S.

Governments are trying to accelerate the shift away from fossil fuels. The Obama administration is providing $2.4 billion in research-and-development grants to electric car and battery manufacturers to improve vehicle battery technology. The Chinese have pledged to put half a million alternative-fuel cars on the road by 2011.

“In 2007 you could barely see an electric car” at the Frankfurt Auto Show, says Agassi, an intense 42-year-old, coolly elegant in a black tieless suit. “If you walked around talking about EVs, everybody assumed you were smoking something.”

Agassi’s business plan is unique among electric-car service providers. Others will make the vehicles. He will lease the batteries to car owners, and sell access to his switching and charging network. He expects to make his money selling miles, much as a cellphone-service provider sells minutes. Subscribers to Agassi’s plan would be entitled to pull into a roadside switching station for a battery change or to plug into a charging station, where dozens of other cars might also be hooked up, for an overnight or workday charge. Agassi estimates his customers will pay no more for battery power than they would spend on gasoline to travel the same distance. As business grows and costs fall, Agassi says, profits will soar. He says eventually he might give cars away, just as cellular-service providers offer free phones to customers with long-term contracts.

Agassi was born in a Tel Aviv suburb—his father is an electrical engineer and his mother a fashion designer—and he began programming computers at age 7. He has already had one hugely successful career. In his early 20s he founded a software company, TopTier, that helped corporations organize data; at age 33, he sold it to the German software giant SAP for $400 million. He later became SAP’s chief of technology. Flush with cash and looking for a new challenge, he turned to global warming. At a gathering of young leaders at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in 2005, Agassi and other attendees were asked, “How do you make the world a better place?”

The challenge, he recalled to me, was “to do something more meaningful than create a new version of software. How do you run a country without oil, on today’s state-of-the-shelf technology?”

It took him a year to consider the options for propelling a vehicle—biofuels, hybrids, hydrogen—before settling on electricity. In the fall of 2006, in a talk he gave at Tel Aviv’s Saban Center for Middle East Policy about running a nation without oil, he mentioned his interest in electric car technology. A week later, Agassi says, he got a call from future Israeli President Shimon Peres, who expressed interest in the concept. Peres introduced Agassi to Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, and, at Davos in 2007, brought him together with Carlos Ghosn, the CEO of Renault. The partnership was formed “very quickly,” says Patrick Pélata, Renault’s chief operating officer. “We were already working on electric cars, and we realized you need three things—a cheap way of charging a battery at home or the office, a quick charge method and a quick drop for people who want their cars for a longer range. Agassi was the only one proposing that.” Agassi quit SAP and, in 2007, founded Better Place in Palo Alto, California. He attracted $200 million from investors, including the Israel Corporation, which owns oil refineries, and investment bank Morgan Stanley. This past January, Agassi announced another $350 million from backers led by the British bank HSBC, raising his investment total to $700 million.

Israel is a natural launching point for electric vehicles because of its small size, seldom-crossed borders and sensitivity to fossil-fuel dependency. The company plans to open its first switching station in Israel near Tel Aviv this year; the goal is to expand to 70 by the end of 2011. Agassi has installed thousands of “charge spots” in garages and parking lots, where drivers can plug in their Renaults for the standard four- to eight-hour, 220-volt recharge. Renault says it hopes to sell 100,000 electric vehicles in Israel and Denmark over the next five years—each equipped with a modified GPS system that will direct drivers to the nearest battery-swapping station or charge point. The vehicle, which can travel about 100 miles on a charge, will reportedly cost $25,000 to $30,000; Better Place hasn’t disclosed the cost of a battery-servicing contract.

Agassi also hopes to work with an Israeli utility company to purchase electricity from solar generators, to reduce his company’s carbon footprint. “The company is looking at the whole process, from the technology inside the car, to the infrastructure, to the charge spots and the connectivity that make all the pieces work together,” says Thilo Koslowski, an automotive analyst with Gartner Incorporated, a Stamford, Connecticut-based consulting firm specializing in high-technology industries. “Agassi has the lead on everybody else.”

Agassi is focusing his rollout on what he calls “transportation islands,” largely self-contained areas that are receptive to electric cars. In Denmark, the largest utility, Dong Energy, is investing $130 million to help provide charge spots and switching stations for Better Place vehicles, and will provide the facilities with wind-generated electricity. Also, the Danish government is temporarily offering citizens a reported $40,000 tax break to buy an electric car—plus free parking in downtown Copenhagen.

In April, Better Place began working with Japan’s largest taxi company to set up a battery-switching station in Tokyo and test four battery-powered cabs. Better Place has plans to operate in Canberra, Australia, and to run a pilot program in Oahu, Hawaii, by 2012.

Agassi is also aiming for the continental United States. He says he has spoken with San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom about building switching stations in the Bay Area. (In December, Newsom and other Bay Area community leaders announced a deal with Nissan—projected cost of the Nissan Leaf is $25,000, after tax credits—to install home-charging units for consumers.) Agassi says he dreams of the day when the big three U.S. automakers sign on to his plan and Better Place infrastructure blankets the country. “With about $3 billion to $5 billion, we can put switching stations across the five major U.S. corridors—West Coast, Northeast, Southeast, Midwest and South,” he says, his voice jumping an octave with enthusiasm. “We can’t fail,” he insists.

But others say he can. The particular battery he has adopted in partnership with Renault may not be accepted by other car manufacturers. That would sharply limit the number of vehicles he could service, or it would force him to stockpile different batteries for different car models, substantially raising his costs. Moreover, lithium-ion battery technology is improving so quickly that Agassi’s switching stations, which cost nearly $1 million apiece, may quickly become as obsolete as eight-track tapes. “If we have a breakthrough, with 300 to 600 miles per charge, the whole thing could be derailed,” says analyst Koslowski.

Better Place also faces difficulties breaking into markets. Without considerable tax incentives, customer rebates and government subsidies for electric car and battery makers, weaning Americans off gasoline will be a challenge. “The U.S. imports more oil than any other country and [gas] prices are the lowest in the West,” Agassi says. Even in Europe, where gasoline costs up to three times as much as it does in the United States, progress has been slower than expected. In Denmark, Agassi promised to have 100,000 charging spots and several thousand cars on the road by 2010, but so far he’s got just 55 spots and no cars. Better Place spokesman Joe Paluska says the company scaled back “while it worked out better design and implementation processes ahead of full-scale commercial launch in 2011.”

Terry Tamminen, an adviser on energy policy to California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and author of Lives Per Gallon: The True Cost of Our Oil Addiction, says Agassi’s faith in battery-powered vehicles is excessive. The technology’s drawbacks, Tamminen says, include the potential drain on the electrical grid and the vast new infrastructure needed—such as tens of thousands of charging spots for the Bay Area alone—and the mileage limitations of even the best batteries. Tamminen, who also served as the head of the California Environmental Protection Agency, believes hydrogen-powered cars will play a role (he drives one himself). They use hydrogen fuel derived mainly from natural gas or other fossil fuels to generate electricity and power the engine; but Tamminen points out that hydrogen fuel can also be derived from water, and dishwasher-size machines that extract hydrogen from water will be available to consumers in 2013. Under the Hydrogen Highway Network, California has installed 30 hydrogen-fueling stations. “Yesterday I drove 150 miles to Palm Springs from Los Angeles in my hydrogen-powered electric car. I refueled in seven minutes and was ready to return that afternoon,” he told me.

But hydrogen fuel faces obstacles, too. U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu last year tried to eliminate federal funding for research into hydrogen cars; he cited the high cost and questionable durability of fuel cells, the expense of building a refueling infrastructure and the reliance of most hydrogen-generating processes on fossil fuels. (Congress, however, restored some funding.)

Agassi told me hydrogen power is an “idiotic idea” because the infrastructure to support it would have to be created from scratch; in contrast, electric batteries rely on the existing power grid.

By 2020, Agassi predicts, half of all cars bought in the United States and Europe will be electric. Others say Agassi’s estimate is overblown. Renault’s Pélata says a better guess might be 10 percent. Rod Lache, an analyst with Deutsche Bank Equity Research, says Better Place could be a financial success even if it occupies a small niche. “It could get 10 percent of the market in Israel and still be hugely profitable. Beyond that, it’s hard to say.”

I caught up with Agassi at Better Place’s new R & D facility, in an industrial park east of Tel Aviv. Agassi, dressed as usual in black, was sitting in a windowless office with unadorned white walls. Carpenters hammered and drilled in the next room. “In Palo Alto I have a cubicle,” he said. “I don’t travel with an entourage. It’s all strictly bare bones.” He had flown from the United States for the final countdown to what his company calls the Alpha Project—the opening of the first switching station and a visitor center, near Tel Aviv. Some 8,000 people have dropped by the center this year to test-drive a Renault EV. Down the hall, in a glass-walled conference room, a score of Better Place employees were working out logistics, such as whether to locate the switching stations underground or at street level.

Next door a pair of software engineers showed me a computer program designed to regulate the electricity flow into the company’s charge spots. A recent simulation by Israel’s main utility indicated that the nation might have to spend about $1 billion on new power plants if every car was electric by 2020. But Better Place says “smart grid management,” or generating electricity only when it’s needed and sending it only where it’s needed, could reduce the number of new plants. Company designer Barak Hershkovitz demonstrated the company’s role in making the grid smarter: five electric cars hooked up at a charge post in the company garage used 20 percent less power than they would have consumed without smart-grid management. Likewise, he told me, to avoid straining the grid, a central computer could keep track of every car being charged in Israel and regulate the juice flow.

To Agassi, such problems are now a matter of fine-tuning. “If [the company’s] first two years were about using brains to solve a puzzle,” Agassi told me, “the next two years are about using muscle to install [the equipment] in the ground.” Soon, he says, gasoline-powered cars will be “a relic of the past,” and maybe ten electric-car companies, including Better Place, will dominate the global market. “Together,” he says, “we will have tipped the entire world.”

Joshua Hammer, a frequent contributor, is based in Berlin. Work by the Jerusalem-based photographer Ahikam Seri previously appeared in Smithsonian in an article about the Dead Sea Scrolls.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)