Building An Arc

Despite poachers, insurgents and political upheaval, India and Nepal’s bold approach to saving wildlife in the Terai Arc just may succeed

It was nearly dusk when A.J.T. Johnsingh set off at his usual forced-march pace down a dusty path hugging the eastern bank of the Ganges River in Rajaji National Park. Johnsingh, one of India's foremost conservation biologists, was looking for tiger tracks, though he hadn't seen any here in years. Every few yards, he trotted off the path and onto the sandy riverbank, calling out the names of birds and plants he spotted along the way. Suddenly he stopped and pointed at a paw print—a tigress. Any other tracks she left had been obliterated by human footprints, bicycle treads and the mingled tracks of cattle, goats, deer, pigs and elephants. But we were thrilled: somewhere, not far away, a tiger was stirring.

India's Rajaji National Park, which lies 140 miles northeast of New Delhi, is bisected by the slow-moving Ganges just south of where the river tumbles out of the Himalayas. In the past, tigers, elephants and other animals had little trouble crossing the river in this region, but now roads, train tracks, irrigation canals, a multitude of temples and ashrams and a military ammunition depot pose a formidable barrier, creating two separate park areas. The riverside forest Johnsingh led us through is the last mile and a half of corridor between the two parts of Rajaji National Park. Johnsingh has struggled for years to keep this crucial forest link intact so that populations of animals don't get stranded on one side or the other.

Johnsingh, a wildlife biologist with the World Wildlife Fund's India branch and the Nature Conservation Foundation, was excited by the prospect that the tigress might venture across the river and mate with tigers in the western half of Rajaji, giving the isolated, declining tiger population there a much-needed boost of fresh genes. "For more than 20 years I've seen the habitat get mostly worse in Rajaji," Johnsingh said. "This tiger's track on the riverbank tells me we might be turning the corner and that maybe we can restore and maintain tigers in this park, and beyond."

The effort to preserve this habitat spanning the Ganges is but a small part of a grand conservation experiment being conducted at the base of the Himalayas in northern India and western Nepal, along a green ribbon of forest and tall grassland called the Terai (Sanskrit for "lowlands") Arc. One of the world's most diverse landscapes, it is also one of the most imperiled. Between Rajaji and Parsa Wildlife Reserve, about 620 miles to the east in Nepal, lie several protected areas that conservationists hope to string together as a stronghold for tigers, leopards, Asian elephants and other endangered species.

The need for such an approach is acute, and growing. Today, India's economic boom threatens to obliterate the 11 percent of the nation that still shelters large mammals. There is a huge demand for wood and stone for construction. New roads, including one called the Golden Quadrilateral, a multilane highway that links India's major cities, gobble up and fragment wildlife habitat. At the same time, many Indians remain desperately poor. Some people poach wild animals to put food on their tables, and they collect wood from protected forests for cooking. Illegal wildlife traders also hire the poor to poach tigers and other animals, paying them money they cannot match at other jobs. The skin and bones of a tiger fetch traders thousands of dollars on the black market.

In Nepal, the problems have been even worse. A deadly conflict has raged for more than a decade between the government and a homegrown Maoist insurgency. In February 2005, King Gyanendra assumed absolute control of the government. Massive pro-democracy demonstrations in Katmandu and other cities, in which 17 protesters were killed and many more injured, forced him to restore Parliament in April of this year. The Maoists have agreed to peace talks, but whether they will now join the political process or return to armed conflict was an open question as this magazine went to press.

Intense fighting in the past five years has put Nepal's tigers, rhinos and elephants at greater risk, because it has diverted law enforcement's attention away from the illegal killing of wild animals, which appears to be on the rise. The hostilities have also scared away tourists—one of the nation's largest sources of foreign exchange. Tourism gives value to wildlife and helps ensure its survival.

In a sense, the protected areas of the Terai Arc frame a big idea—that tigers, elephants, rhinos and human beings can live together along the base of the Himalayas, one of the most beautiful places on earth. The notion of creating vast international conservation areas by linking smaller ones isn't new—some conservationists have proposed connecting Yellowstone to the Yukon, for instance—but nowhere has the approach gone as far as it has in the Terai Arc. This past fall, we traveled the length of the region on behalf of the Smithsonian's National Zoological Park and the conservation organization Save the Tiger Fund. On previous visits we'd seen signs of flourishing wildlife. But given a recent plague of poaching in India and the hostilities in Nepal, we wondered how much would be left.

The brothers A. S. and N. S. Negi are separated by 18 years of age but are united in their passion for conservation. N. S., now 81, served for many years as a forest ranger in Corbett National Park, 20 miles to the east of Rajaji; A. S. Negi was Corbett's director in the early 1990s. Now both retired, the brothers and Johnsingh formed a small organization called Operation Eye of the Tiger in 1996 to protect tigers and preserve their beloved park, named for Jim Corbett, the British hunter who killed numerous man-eating tigers in northern India in the first half of the 20th century. We met up with the Negi brothers in the bucolic Mandal Valley that forms the northern boundary of the park.

Eye of the Tiger has helped 1,200 families in the area buy liquid petroleum gas connectors, which allows them to cook with gas instead of wood. This has helped reduce the amount of firewood burned by each family by up to 6,600 to 8,800 pounds per year. Not only does this save the forest for wildlife, it also saves women and girls from the arduous task of collecting firewood—and the danger of encountering a tiger or elephant. Unfortunately, A. S. Negi says, the price of bottled gas, once low, is rising in energy-hungry India and may soon be out of reach of most villagers. Through additional subsidies, the Negis told us, they persuaded some villagers to replace their free-ranging scrub cattle, which graze in wildlife habitat, with animals that yield more milk and are not allowed to roam. But we wondered what such small steps might have to do with tiger conservation.

The next morning we found out. We drove to the border of the tiger reserve and hiked in, and soon we spotted the tracks of a tiger that had followed the very trail we were on for about 100 yards before it padded overland to the river below. This tiger would make an easy mark for a poacher, but it was quite fearlessly there, sharing this valley with the villagers. Before the Negis began their work, poaching was rampant in this area. It seems their attention to the villagers has indeed made a difference, and we think the lesson is clear: if tigers are to survive in this landscape, it will happen one village at a time.

The next morning we found out. We drove to the border of the tiger reserve and hiked in, and soon we spotted the tracks of a tiger that had followed the very trail we were on for about 100 yards before it padded overland to the river below. This tiger would make an easy mark for a poacher, but it was quite fearlessly there, sharing this valley with the villagers. Before the Negis began their work, poaching was rampant in this area. It seems their attention to the villagers has indeed made a difference, and we think the lesson is clear: if tigers are to survive in this landscape, it will happen one village at a time.

Most of the forest between Corbett and the Royal Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve in Nepal is managed to produce timber, with its teak and eucalyptus trees planted in straight lines. But the area is also rich in the big rocks favored for construction materials. Johnsingh pointed to men hauling boulders in a dry riverbed. From there the boulders were pitched onto trucks and driven to railway heads, where workers crushed them with sledgehammers. This backbreaking work is done by the very poor, who camp in squalor where they toil and survive by gathering firewood and poaching in the surrounding forests. Boulder mining was banned in some Indian parks, whereupon the miners promptly moved their operations outside the protected areas. Johnsingh believes that a better solution would be to permit boulder mining along developed stretches of riverbed and prohibit it where wildlife needs passageways.

Emerging from the forest about 20 miles from the Nepal border, we inched in our four-wheel-drive vehicle along a two-lane highway crowded with pedestrians and an impossible assortment of cattle carts, bicycles and motorcycles, overflowing pedicabs, taxis, cars large and small, buses, trucks and tractor-pulled trailers. This is a prosperous area, thanks to dams that provide power to villages and water for irrigated agriculture. No tiger could navigate this maze, but Johnsingh has identified a potential forest corridor to the north through which it could make its way.

Entering Nepal, Johnsingh hands us over to Mahendra Shrestha, director of the Save the Tiger Fund. We had been uneasy about going into Nepal. The conflict with the Maoists has killed some 13,000 people here since 1996, most of them in the very countryside to which we were headed. In summer 2005, five of Shrestha's field assistants were killed when their jeep ran over a land mine likely planted by the Maoists. But in September 2005, the insurgents had begun a unilateral, four-month-long cease-fire, and our trip had been timed to coincide with it.

We spent the night in Mahendranagar, a small town at the edge of Shuklaphanta. A battalion of about 600 soldiers is stationed inside and around the park. In the 1970s, when poaching of rhinos and tigers was rampant, the Royal Nepalese Army took over security in Nepal's national parks and wildlife reserves. Since the insurgency began, the army has devoted more effort to quelling it and defending itself than to patrolling for poachers. Soldiers were moved from forest outposts to fortified bases, giving both Maoists and poachers greater freedom in the forests.

Shuklaphanta contains 40 square miles of grassland surrounded by a forest of sal trees. Some of the tallest grasses in the world, standing more than 20 feet high, thrive here. Driving along a rutted dirt road, we saw wild boar, spotted deer and even a small herd of hog deer—the rarest deer of the Terai Arc. But we had come to find out how tigers, leopards, elephants and rhinos, so attractive to poachers, were faring with the army preoccupied with the Maoists.

A glimpse of two elephants, one rhino track and one tiger track next to a water hole bolstered our spirits. In fact, the park's warden, Tika Ram Adhikari, told us that camera traps had recently documented 17 adult tigers here, for a total estimated population of 30, which means they're as dense in this area as in any place they live.

Adhikari's usual ebullience evaporated at a water hole littered with dead and dying fish. Cans of pesticide—used to stun and kill fish so they float to the surface—lay on the shore alongside fishing nets. Poachers had dropped the tools of their trade and vanished upon our arrival. At another nearby water hole, a distraught Adhikari pointed out a set of tiger tracks, normally a cause for cheer but now worrisome. What if the tiger had drunk from the poisoned pond? Even more troubling was the thought that local attitudes toward the park and its wildlife might be shifting.

From Shuklaphanta we continued east along the highway toward Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal's next protected area, stopping often at heavily fortified checkpoints so that armed soldiers could inspect our credentials. The soldiers' behavior was entirely professional; these were not hopped-up teenagers brandishing rifles in our faces. But we stayed alert, aware that there are good and bad guys on both sides of the conflict. For example, the Nepalese Army has been accused of torture and other abuses, and Maoists have been known to invite people to step safely outside before blowing up a building.

Maoist insurgents control more than half of Royal Bardia National Park's 375 square miles. As we sipped scotch after dinner at Bardia's nearly empty Tiger Tops Karnali Lodge, the evening's quiet was shattered by the sounds of shouting, clashing gongs and thumping drums—villagers trying to drive off elephants intent on eating unharvested rice. We heard the same ruckus the next two nights. With noise pretty much their only defense, the villagers are outmatched by the crop-raiding pachyderms. Between eating it and stomping it, just a few elephants can destroy a village's rice crop in a night or two.

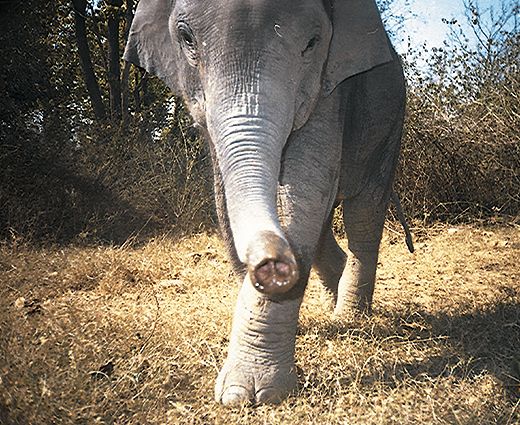

We caught up with the marauders the next afternoon on an elephant-back tour of the park. Our trained elephants sensed the presence of their wild relatives in a dense patch of trees, and our elephant drivers moved cautiously toward them so we could get a closer look. But with the first glimpse, the animals we were riding backed away, and we retreated hastily across a river. Three wild males—which we nicknamed the Bad Boys of Bardia—glowered at us from the other side until, with the light failing, we finally departed.

Wild elephants disappeared from Bardia many years ago, but in the early 1990s, about 40 somehow found their way back. No one is sure where they came from—perhaps as far away as Corbett National Park—and today they number between 65 and 93. Copying a model pioneered in Chitwan, conservationists in Bardia worked with local community groups to protect this forest and help them raise and market such cash crops as fruit and medicinal herbs.

In the buffer zone around Bardia, we met with members of one of these associations, the Kalpana Women’s User Group. They told us that one recently completed project is a watchtower from which farmers can spot wild elephants. They also told us they have purchased biogas units so they no longer have to collect fuel wood in the forest. (Biogas units convert human and animal waste into methane, which is used to fuel stoves and lanterns.) Last year, the women won a conservation award from the World Wildlife Fund program in Nepal, and they used the 50,000 Nepalese rupee prize (about $700) to lend money to members for small enterprises such as pig and goat farms. These women, with sheer angry numbers, have also arrested timber poachers and received a share of the fines imposed on the culprits.

But success breeds problems. In the Basanta Forest, between Shuklaphanta and Bardia, tigers killed four people in 2005, and 30 elephants destroyed nine houses. "We like to have the wildlife back," a member of a Basanta community group said to us. "Now what are you going to do about it?" There is no easy answer.

It’s a day’s drive—about 300 miles—from Bardia to Nepal's Royal Chitwan National Park. Though tigers live in the forests between the two parks, bustling towns in the river canyons between them prevent the animals from moving freely from one to the other.

Our excitement at finding fresh tiger tracks on a riverbank near a Chitwan beach faded after we entered the park itself. Moving in and out of forest and grassland, we scoured the landscape looking for rhinos. In 2000, we saw so many—at least a dozen during a three-hour elephant ride—that they lost their allure. But on this morning, only five years later, we spotted just one.

Only organized poaching could explain such large losses. Poaching rhinos for their horns (which aren't really horns but compacted masses of hair used in traditional Chinese medicine—not as an aphrodisiac as is widely believed) was rampant in the 1960s. After poaching was curbed by the army beginning around 1975, rhino numbers rapidly recovered. But here, as in Bardia and Shuklaphanta, the Nepalese Army abandoned the park's interior to fight Maoists, and the poachers returned in force.

Eventually, though, the loss of the park's 200 or 300 rhinos spurred warden Shiva Raj Bhatta to action. He told us that in the few months before our visit, he had arrested more than 80 poachers—all now languishing in a local jail. Under the leadership of a hard-nosed colonel, the army, too, had reportedly stepped up its anti-poaching patrols.

More encouraging still, Chuck McDougal, a longtime Smithsonian research associate and a tiger watcher for more than 30 years, informed us that a census he'd just completed found all 18 tigers in western Chitwan present and accounted for. What’s more, McDougal reported, a pair of wild elephants were turning up regularly—a mixed blessing. And the first group of American tourists in more than two years had just checked in at Chitwan's first tourist lodge.

In 2005, Nepal recorded 277,000 foreign visitors, down from 492,000 in 1999. Although tourists have largely escaped the attention of Maoist rebels, some visitors have been forced to pay a "tax" to armed insurgents. The possibility of getting caught in a crossfire or of being blown up by one of the mines that lurk under certain roads has kept tourists away. In Baghmara, on the northern border of Chitwan, tourist dollars offer an incentive to villages to tolerate tigers and rhinos, but with tourism at a nadir and tiger attacks on the rise, tolerance is wearing thin.

The Save the Tiger Fund recently reported that tigers now live in only 7 percent of their historic ranges across Asia. At the same time, the amount of habitat occupied by tigers has fallen by 40 percent in the last ten years. After 35 years of working to promote the conservation of tigers and other large mammals, we find these statistics terribly depressing. But the Terai Arc is one of the few bright spots highlighted in the report.

Despite the obstacles—from boulder-mining to crop-raiding—our traverse of the arc largely confirmed the report's optimism and helped dispel our gloom. Here, tiger numbers are increasing and tiger habitat is improving. Elephant numbers are also on the rise, and rhinos will surely rebound if anti-poaching efforts can be resumed. Local people are benefiting from conservation, too, although much more needs to be done—such as surrounding crops with trenches or plants unpalatable to animals and building more watchtowers—to protect them from wild animals roaming their backyards.

If the goal of a connected, international conservation landscape comes to fruition, the arc may become one of the rare places where tigers, rhinos and Asian elephants survive in the wild. How it fares will tell us whether people and wildlife can thrive together or if that is just a dream.

John Seidensticker is a scientist at Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park and Susan Lumpkin is communications director of Friends of the National Zoo.